Horizontal imbalance: Challenges of delivering equalization

The well-established principle for resolving horizontal imbalance consistent with equity and efficiency, as practiced by major federal countries, is called fiscal capacity equalization. The underlying idea is that fiscal transfers compensate for a deficiency in fiscal capacity, but not that in tax effort. In India, fiscal capacity equalization is delivered at least partially through the ‘distance criterion’. The distance criterion is supplemented by a number of other devolution criteria.

The distance criterion involves a re-distribution from states with higher fiscal capacity to lower fiscal capacity. For lower per capita GSDP states, the distances from the benchmark and the relative population size have both increased, accompanied by a lowering of weight attached to the distance criterion. This implies larger redistribution to achieve the same degree of equalization.

After FC14’s recommendations, the GoI has shown reluctance to accept state specific and purpose specific grants that facilitated augmenting the extent of equalization or delivery of other welfare objectives by finer targeting. In this context, either the share of states in tax devolution may be reduced from 42% or 41% of the sharable pool or tax devolution framework should be modified to impart to it greater targeting capacity. There is a need to evolve the next generation of devolution criteria1.

Fiscal imbalance: Issues of debt and deficit sustainability

The FC16 has not been directly asked to examine the sustainability of debt and fiscal deficit for the GoI and the states. However, FC16 should and can consider this under the provisions of Articles 280 (d) making a reference to ‘interest of sound finance’ and under constitutional articles 292 and 293 dealing with central and state borrowing. Also, FC grants to states ‘in need of assistance’ as per article 275 (1), cannot be normatively determined until there is a normative determination of the interest payments and revenue expenditures of states. Thus, fiscal, vertical, and horizontal imbalances require to be jointly resolved.

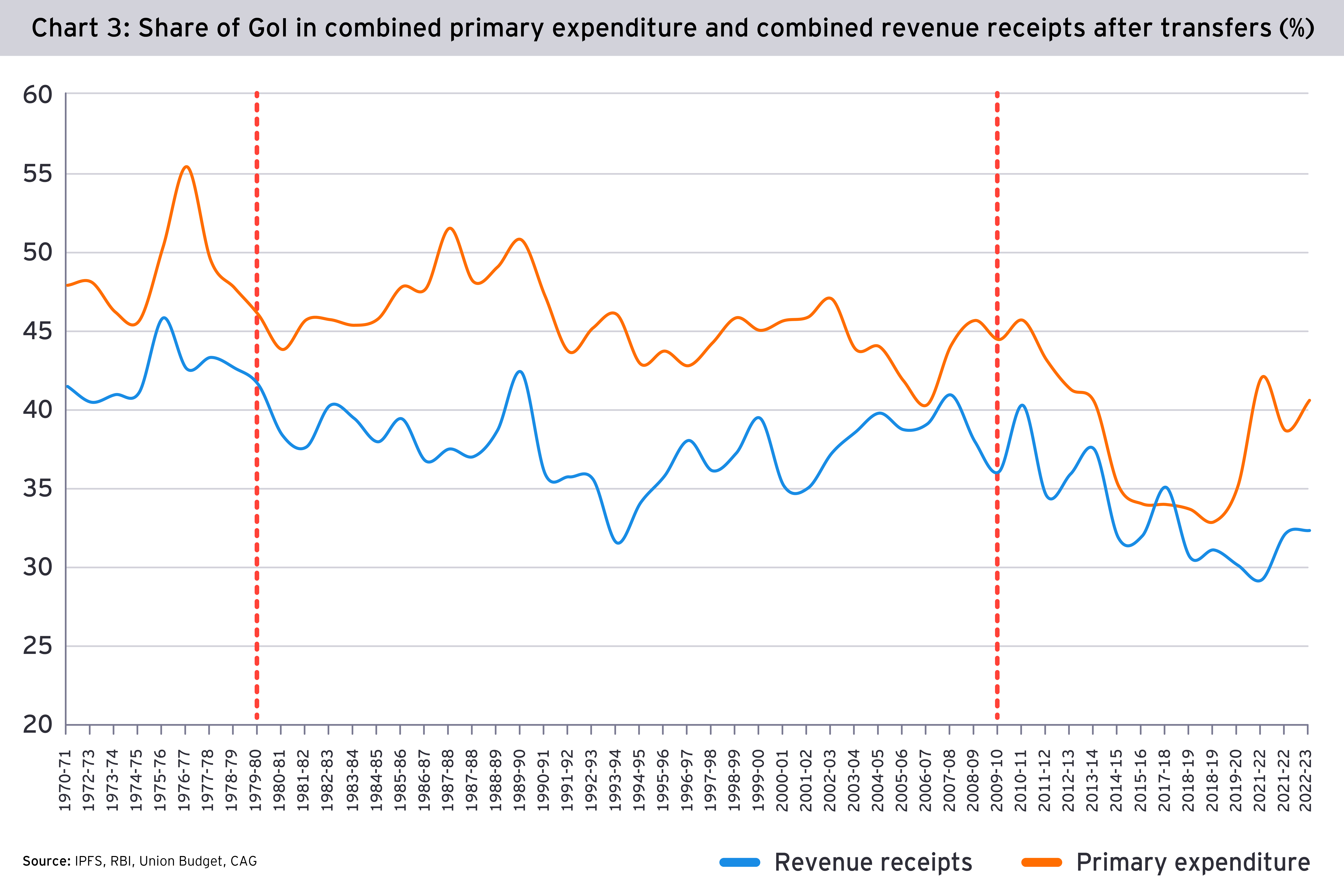

The issue of symmetry in fiscal deficit targets for the GoI and the states is linked to the way vertical transfers from the GoI to states have evolved. Here, it is important to compare the share of GoI in the combined revenue receipts after fiscal transfers with its share in the combined primary expenditures (Chart 3).