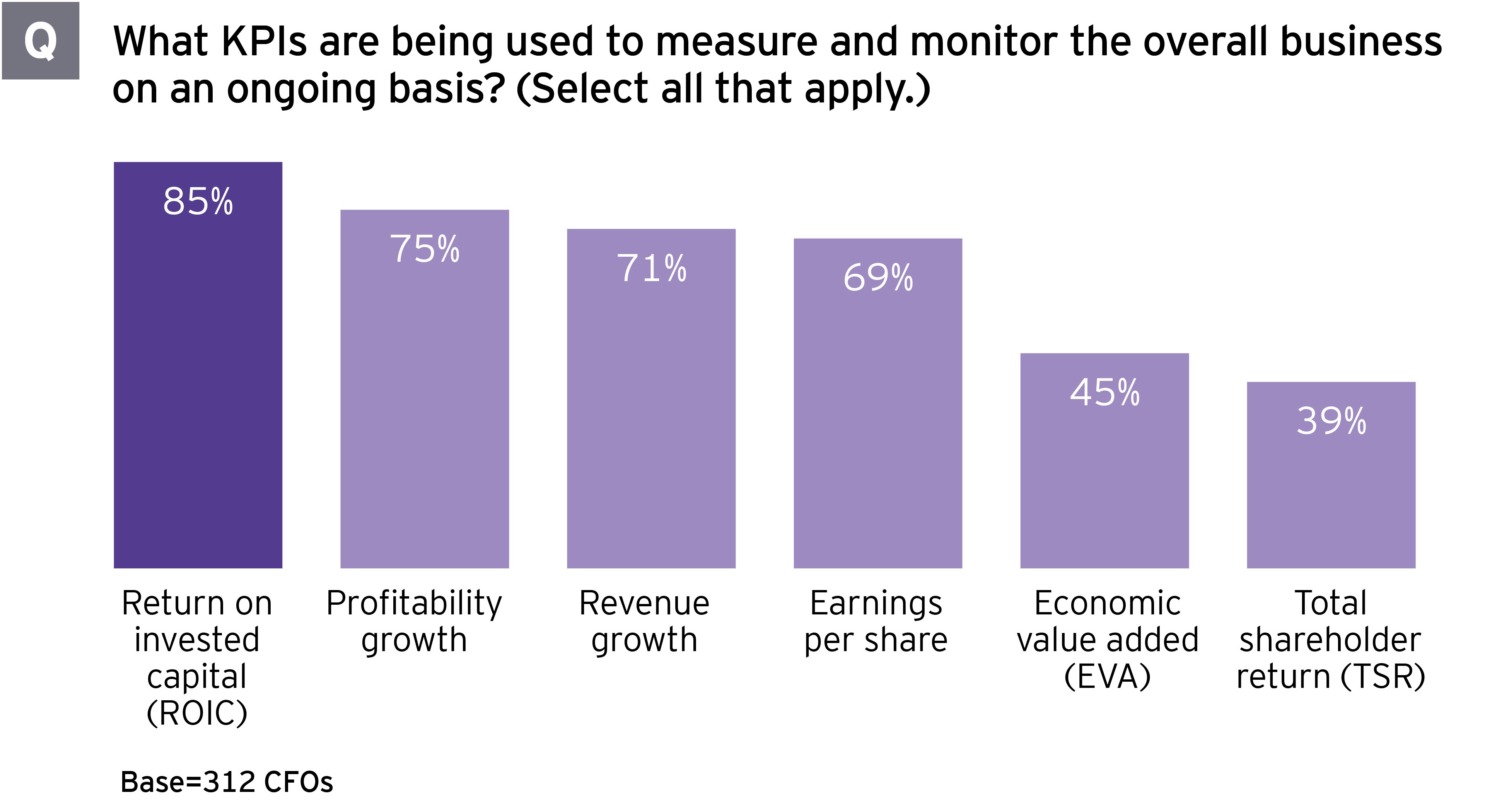

KPIs also should not remain static. If a KPI turns out to not be a predictor of future growth, or if business priorities change, new KPIs should be considered. But only 56% of CFOs say they changed their KPI rankings in the past three years. Similarly, scorecard weightings need to be revised in light of the business’s performance.

Understanding the enterprise strategy and the qualitative and quantitative metrics driving it can be particularly valuable for CFOs, allowing them to move beyond financial planning and reporting to making divestment decisions and otherwise set strategy.

Align compensation with portfolio performance

Management’s compensation can also pose an unforeseen obstacle to decisive portfolio management. It is important to avoid incentivizing the senior team to retain businesses through revenue-based pay and rewards tied to short-term performance that could be adversely affected by divestments.

Instead, overall portfolio performance and long-term value creation should be factored into compensation.

Activists rebound, with ESG on their radar

After a brief, pandemic-induced hiatus during the 2020 proxy season, activists are back: more than 120 campaigns were launched in the first quarter of 2021, according to Activist Insight.

Nearly three-quarters of activists (74%) say the pandemic has affected the way they look at targets. In particular, activists are focusing more on the flexibility of the target companies’ cost base (80%) and ability to adapt to different routes to market (70%).

ESG issues are also now on the radar as areas of leverage to sway shareholder votes toward activists in the event of a proxy fight. However, the traditional activist focus on growing shareholder value still drives most activist campaigns as they seek returns. Overly complex divisional structures (78%), board composition or lack of refresh (70%), and suboptimal allocation of growth capital (63%) were most frequently named as the top factors in identifying new investment opportunities.

Divesting is one way that management can demonstrate that it is looking to maximize shareholder value; 89% of activists note campaigns will recommend carving out non-core or underperforming businesses. Moreover, two-thirds (67%) say they expect a divestment to be announced three to six months after they announce an investment in a company.

ESG is becoming part of the activist playbook

While ESG is not yet a prominent factor in identifying target companies, environmental and social considerations are emerging as a more significant prompt for activism as they grow more entwined with long-term value. ESG has become a focus area for boards, with sustainability committees increasingly part of the governance structure. Diversity and inclusion issues are also posing a reputational risk for some companies.

Companies are already restructuring to split themselves into environmentally friendly and unfriendly portions based on their emissions profile and use of coal. Related to diversity, some have begun considering to whom they are selling their businesses and potentially trying to develop a more diverse pool of potential buyers. Some are also taking into account the make-up of senior management and the board when diversifying.

No matter the focus of the campaign, failure to respond may be costly and lead to changes in the management team or board. Executives need to demonstrate that their businesses support long-term value creation. Without strong rationale for a business remaining part of the portfolio, an activist will eventually try to force the separation.

Decide what to divest and take action

Now is a great time to be a seller as buyers, including PE firms with a propensity to acquire corporate carve-outs, are flush with cash in this low-interest-rate environment.

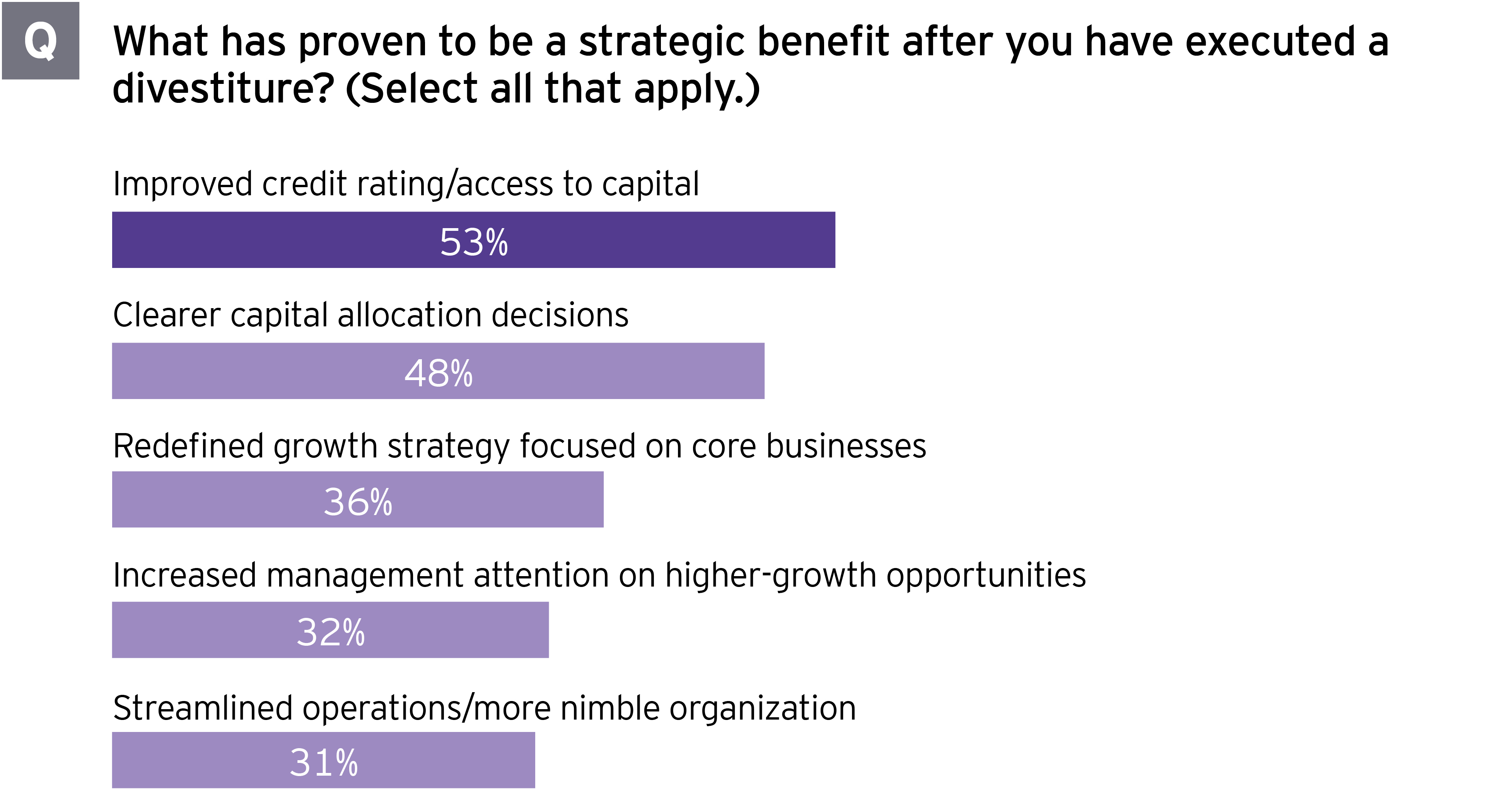

Companies should not wait to act until growth has stalled or for an activist investor to come calling. More than a third of companies (37%) say activist activity in their sector prompted a review of strategic alternatives in the past 12 months.

Even if a divestment decision is more challenging while a business is still healthy, it is far more saleable at this point. And even smaller businesses that do not require much capital investment can still be a management distraction.

There are instances where the cyclical nature of a business unit can entice a company into holding onto it. For example, companies in cyclical industries, such as steel or oil and gas, identify a business as a divestment candidate at the bottom of the cycle, but have held on to see if it can be sold for a higher price when the cycle turns. However, when the business does improve, management may decide not to divest. Then the cycle turns, the process is repeated and the decision to divest is repeatedly postponed.

To break that cycle, CFOs may want to consider recommending strategic alternatives such as:

- Staged or stepped exits: Selling a majority interest while maintaining a minority investment can provide the best of both worlds. It removes the business from the balance sheet and brings in new external capital that a non-core holding will not receive under a strategically determined capital allocation plan. At the same time, it provides continued exposure to the business’s upside through the reduced stake retained.

- Asset-light approach: Companies may take this approach if a business is important to the firm’s operations, but not a core competency. One example is Dow’s sale of its US and Canadian rail infrastructure in July 2020 for about $310m. Notably, the transaction also included a long-term service agreement with the buyer, logistics firm Watco, thereby allowing Dow to maintain the necessary services while removing the rail assets from its portfolio.

- Joint ventures with strategic partners: This structure may be particularly attractive if the business is an important supplier to the parent company.