Low wages growth is a threat to Australia’s economic success

Forecasts for wage growth are a key determinant of monetary and fiscal policy settings so there is a lot at stake in getting them right. Private wages growth was at a record low of 1.2 per cent in the year to September 2020. Moreover, Commonwealth Treasury is forecasting growth of just 1¼ per cent to June 2022. Given that wages growth of 2.1 per cent, the average growth seen in the five years prior to COVID, was considered weak and well below the long run average of 3.2 per cent, the forecast numbers are very weak.

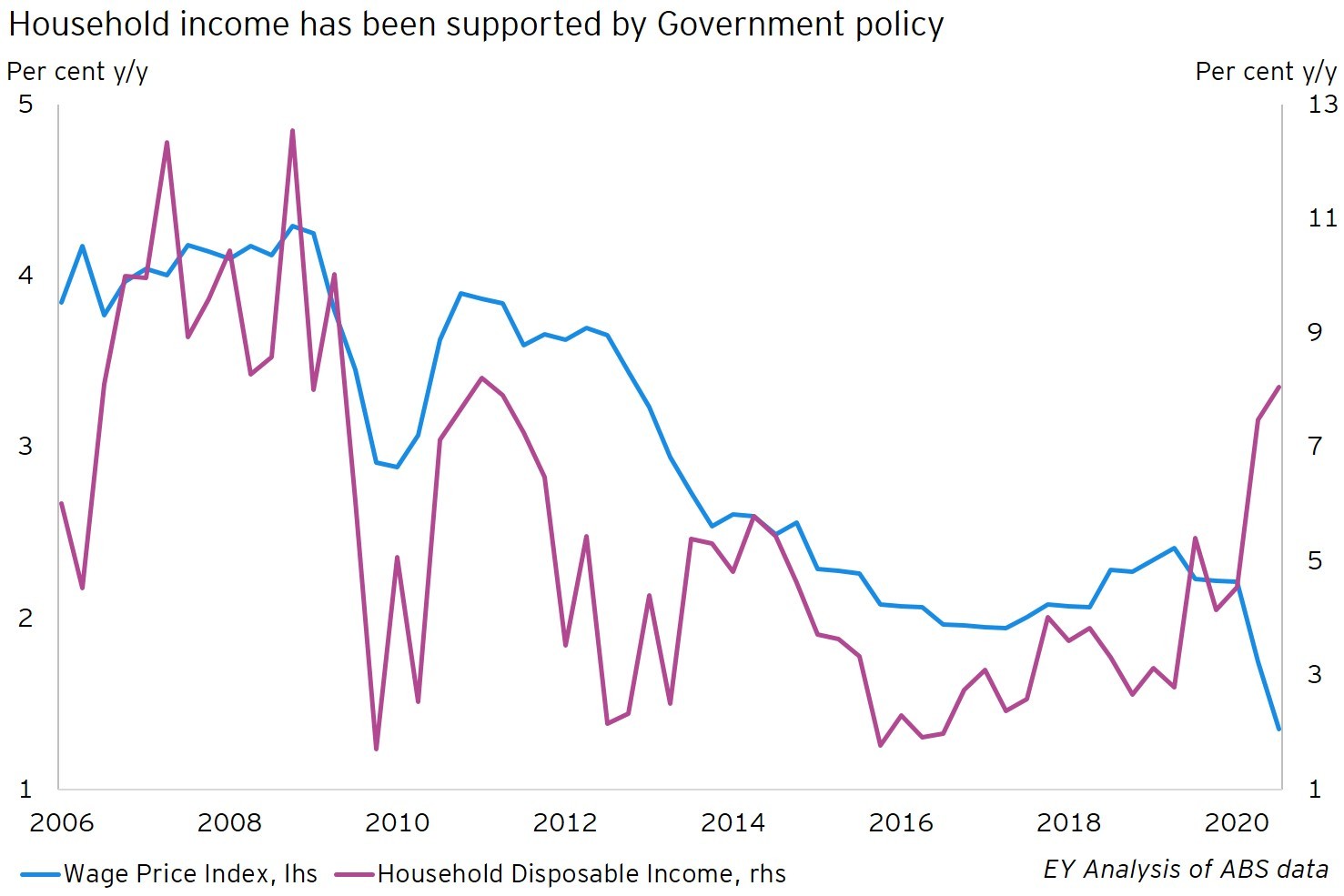

Moreover, if we take into account forecast inflation, real wages growth is set to go backwards over the next two financial years.

Only using traditional models that link unemployment to wage growth risks actual wage growth falling short of forecasts. In today’s context, the risk is negative real wages growth.

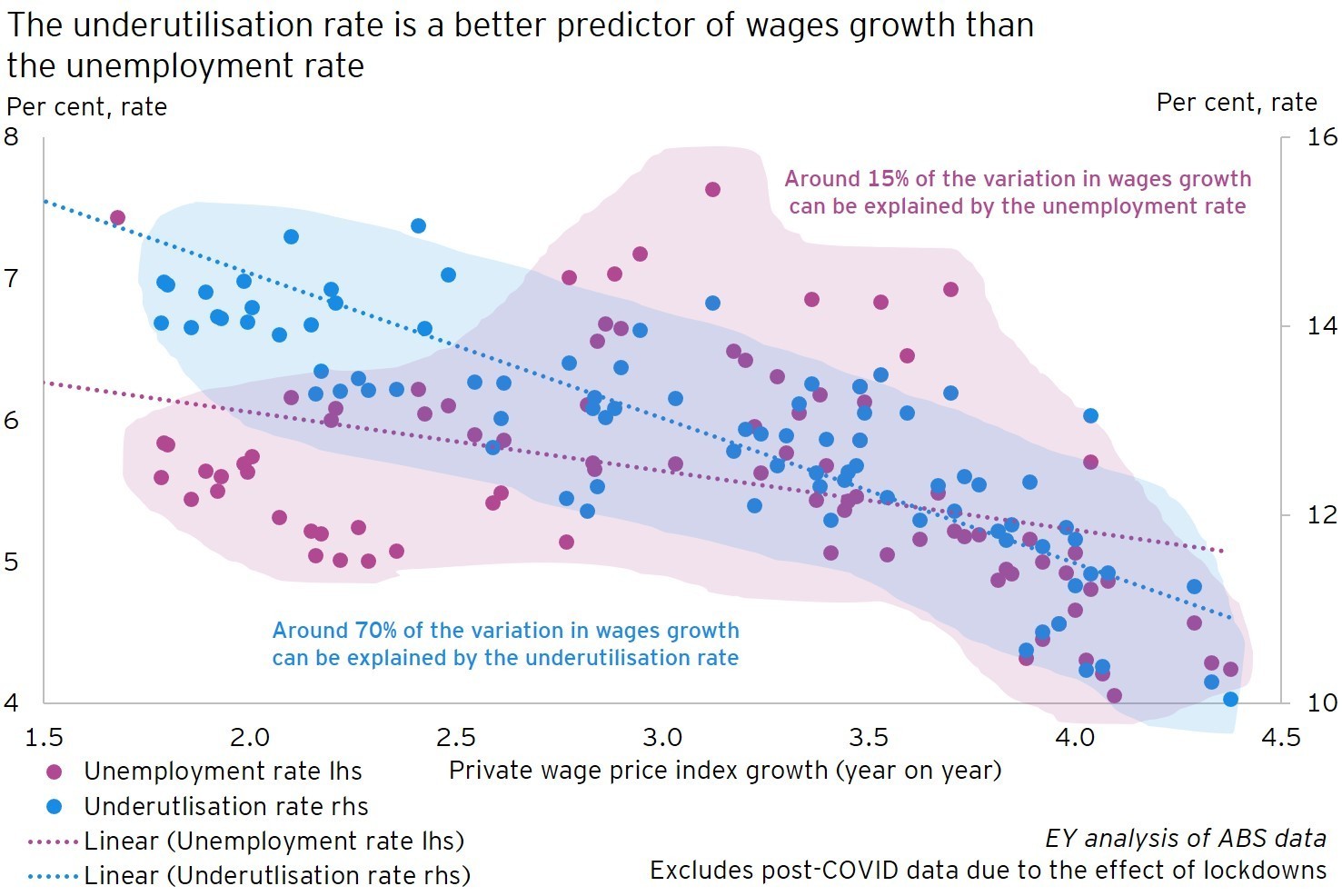

Wage forecasts are typically based on the gap between the unemployment rate, and what is considered full employment, currently estimated to be 4.5 per cent.

If we were to forecast wage growth based on underutilisation instead, that would require a commensurate marker of full capacity. Based on EY modelling, we estimate that figure to be around 12 per cent.

At the end of 2020, the gap between under-utilisation and full capacity was 3.5 percentage points, indicating more spare capacity than the 2.5 percentage point gap between unemployment and estimated full employment.

Using the RBA’s forecasting models*, EY analysis of this disparity suggests wages growth could be up to ½ per cent lower on average over the next four years than compared to a model which uses just the unemployment rate. Such a scenario would weigh on Australia’s largest sector – our households’ ability to consume – and limit our economy’s potential to grow over the coming years.

Our modelling suggests this would translate into a 0.6 per cent hit to GDP over four years, resulting in GDP being $12 billion lower in 2024.

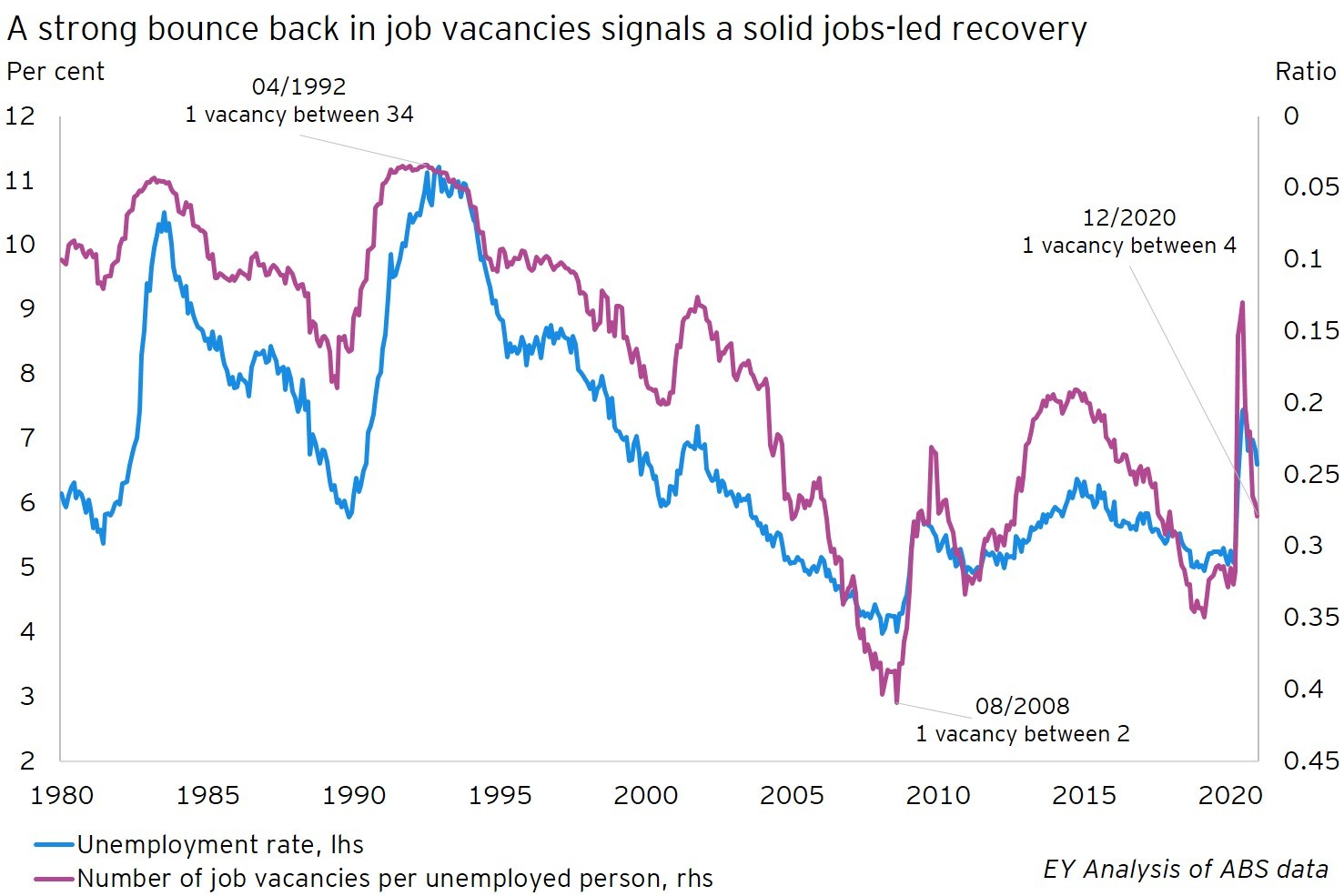

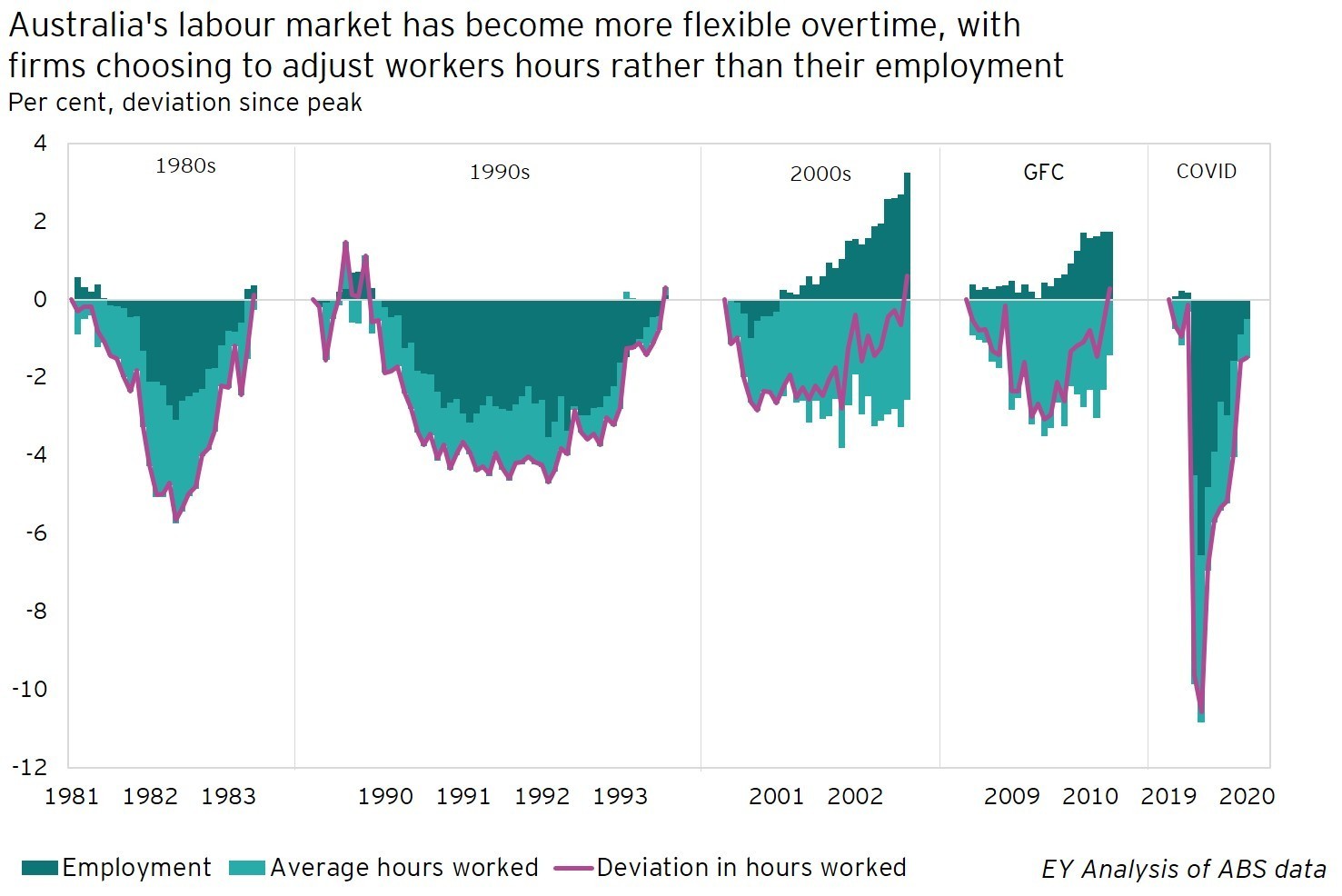

While policy makers and economists were already beginning to consider the flow on effect of using underutilisation and hours worked rather than traditional singular markers of unemployment, the COVI-19 recession has sharpened the urgency around adopting these measures more broadly and applying them as a central benchmark in policy making, particularly when we consider the prospect that wages could fall in real terms if we’re not careful.

What can be done to lift wage growth, and will anything be done?

Driving wage growth requires policies designed to generate jobs but also boost aggregate demand to increase hours worked and lower underemployment.

This can be achieved by direct government spending (infrastructure spending and service delivery) or by pushing the economy faster and more productively, or both. Given the amount of fiscal stimulus already in the system, and with monetary policy already at ultra-accommodative settings, productivity enhancing reform is ever more important.

It is critical that the focus of fiscal policy shifts from respond and recover, to recover and reform. However, given the political cycle (and the prospect of a Federal election later this year) and the lack conversation about reform, it does not feel like we are gearing up for a hard-hitting reform budget this year. Reform may have to wait for 2022, and we may just face a period of very stagnant income growth as a result.

*Two scenarios for underemployment were considered in a modified RBA model based on its MARTIN wages and macroeconomic model. These included the underutilisation rate and EY’s estimate of the underutilisation NAIRU. First was a widening of the gap between unemployment and underemployment – similar to what occurred following the end of mining investment boom. The second was one where underemployment did not decline from its current level, while the unemployment rate continued its downward trend as expected by the RBA. Both scenarios produced similar results for weaker wages growth relative to the RBA’s baseline wages model.