Reputational capital

Many presidents cite the continuing importance of rankings in attracting students as well as funders. Many leaders try to emulate the top-ranking universities, but this is strategy is costly. To climb in the rankings, colleges and universities need to make substantial investments in research, marketing, academic offerings, facilities and financial aid.

Many institutions cannot afford this kind of investment, especially at a time when enrollment is declining and research dollars are stagnant, pushing many in the direction of increasing their debt levels. While there will always be a set of students interested in top-tier research universities, this is not the majority of students. Some university presidents understand this and have identified other ways of increasing their institutions’ reputational capital.

When schools start redefining “reputation” as “relevance,” this opens up more pathways for schools to pursue. EY-Parthenon interviews found that these approaches tended to fall into three categories:

- Alignment with local economy: Many schools understand that they are a key part of the local economy and have developed a reputation for helping to meet local workforce needs or aligning their research or areas of study to local economic needs.

- Targeting student populations: Many schools have identified a student population that they want to serve and have developed services and supports to serve that population.

- Curricular niche: Schools that choose to specialize in a certain area of study or approach to the curriculum create a niche that can help to attract students, especially when the niche is responsive to students’ needs and desires.

These approaches are often enhanced by higher education partnering with industry. Universities can successfully navigate these partnerships when they set clear expectations and outline roles and responsibilities clearly.

Financial capital

Compared to the other forms of higher education capital, financial capital is relatively easy to quantify, but hard to manage. The number of colleges and universities that have integrated their financial assets and borrowing power in a single decision support tool that enables them to match sources to uses is much smaller than in corporations of similar size. The need for a sophisticated financial strategy is even more important given long-term financial trends in higher education:

- The funding model of public higher education is broken: Public support for state schools has dropped to historically low levels, and tuition, especially for out-of-state students, has increased in direct proportion. Since public research universities educate 80 percent of all undergraduate and graduate students in the US, this trend poses a massive challenge for the sector as a whole.

- There is massive concentration of wealth: Of the 805 schools with endowments in the United States, the top 10 university endowments control 35% of the total $515 billion in endowments, or $180 billion. The top 40 control two-thirds of the endowment wealth.

- Scarcity and abundance skew the process of innovation: With federal and state funding stagnant or declining, relationships with private entities (industry and individuals) are becoming more integral to an institution’s future, and the ability to manage financial capital in the service of a well-defined strategy is vital.

Physical capital

Physical capital is the most tangible form of higher education capital and is the first impression a student will have of a school. Students are demanding more technology as well as other services and amenities on a campus that will help them enhance their experience and better prepare them for the workforce. The campuses that will be the most successful in the long run are those that combine the on-campus experience with the technologies of personalized, online learning and that redefine the learning experience for the millennial generation.

Moreover, innovation is necessary for universities of all types to meet their physical capital needs. Innovation is not just necessary in the way a building looks, but in the way universities think about utilization. Universities that leverage data to understand utilization have had success in making more efficient use of space. In addition, new uses of technology and areas of research create demand for new types and uses of space.

As financial pressure increases, schools will need to be even more creative in how they think about the use and costs of their physical spaces. There are creative ways of financing, and the nonprofit status of schools provides them with many opportunities, including public partnerships that support the creation of new spaces in a way that benefits the local community as well as the school.

Institutional perspectives

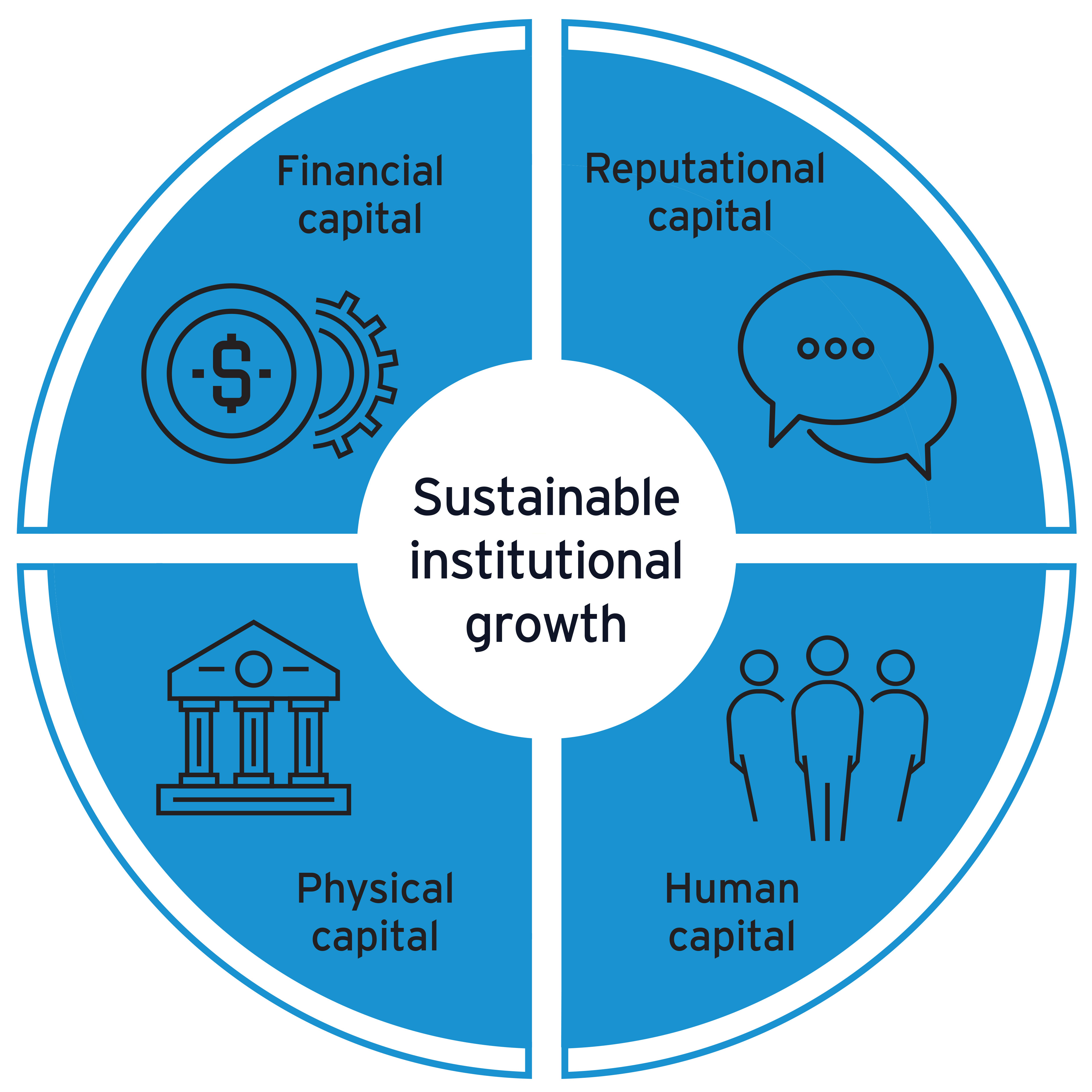

Across the four areas of capital — human, reputational, financial and physical — there are challenges. On the following pages are a selection of perspectives that highlight the innovative ways presidents are addressing these challenges across all four areas of university capital.

Higher education capital assets