The COVID-19 pandemic has dealt a severe blow to an already stressed economy.

In FY21, the Indian economy nearly lost the full month of April and a relatively large part of May 2020 due to the nationwide hard lockdown. Purchasing Managers' Index (PMI) for manufacturing and services contracted to unprecedented levels of 27.4 and 5.4 respectively in April 2020, while growth in bank credit remained subdued at 6.7% in the fortnight ending 24 April 2020. In March 2020, Index of Industrial Production (IIP) contracted by (-)16.7%, its lowest level in the 2011-12 base series. Contraction in power consumption increased considerably to (-) 24.7% in April 2020 reflecting a sharp fall in domestic demand. At (-) 60.3% in April 2020, contraction in exports was the sharpest since 1991 reflecting global and domestic supply disruptions. With respect to automobile sales, information from major players in the sector indicates zero domestic sales in April 2020[1].

India’s growth under challenge: distinguishing acute ailment from chronic

Recent assessments by various analysts have significantly lowered India’s growth prospects for FY21. In a release dated 8 May 2020[2], Nomura projected a contraction of (-) 5.2% for India. On 17 May 2020[3], Goldman Sachs also projected a contraction of (-) 5.0%. Available growth forecasts vary from (-) 5.2% to 4%, showing a wide range of 9.2% points. This only indicates significant uncertainty in the assessment of the economic impact of COVID-19 on the Indian economy by domestic and international observers. The actual outcome is likely to depend on (a) the pace at which the Indian economy opens up, (b) the magnitude and composition of fiscal stimulus over and above the budgeted expenditures, (c) the impact of the monetary stimulus, and (d) the effectiveness of expenditure reprioritization by the central and state governments as compared to their respective budget estimates.

The Indian economy suffers from a chronic investment slowdown on which an acute breakdown of economic activities has been overlaid due to the lockdown. This has led to the possibility of both GDP and tax revenues slipping into a contraction in FY21 perhaps for the first time in India’s post-independence history if we consider these growth rates on an annual basis. On a trend basis, real GDP growth has been falling consistently from a peak of 6.9% in 2010-11 to the currently estimated trend level of 6.0% in FY20. The actual growth in FY20 has turned out to be 4.2%, that is, 1.8% points below the trend growth.

In the case of tax revenues, the trend growth rate had peaked at 16.8% in FY08. Since then the tax revenue growth on trend basis has been falling. By FY20, it is estimated to be about 5.8% while actual tax revenue growth has contracted by (-) 3.4%. This has significantly squeezed the available fiscal space.

Strategizing stimulus: Monetary and fiscal

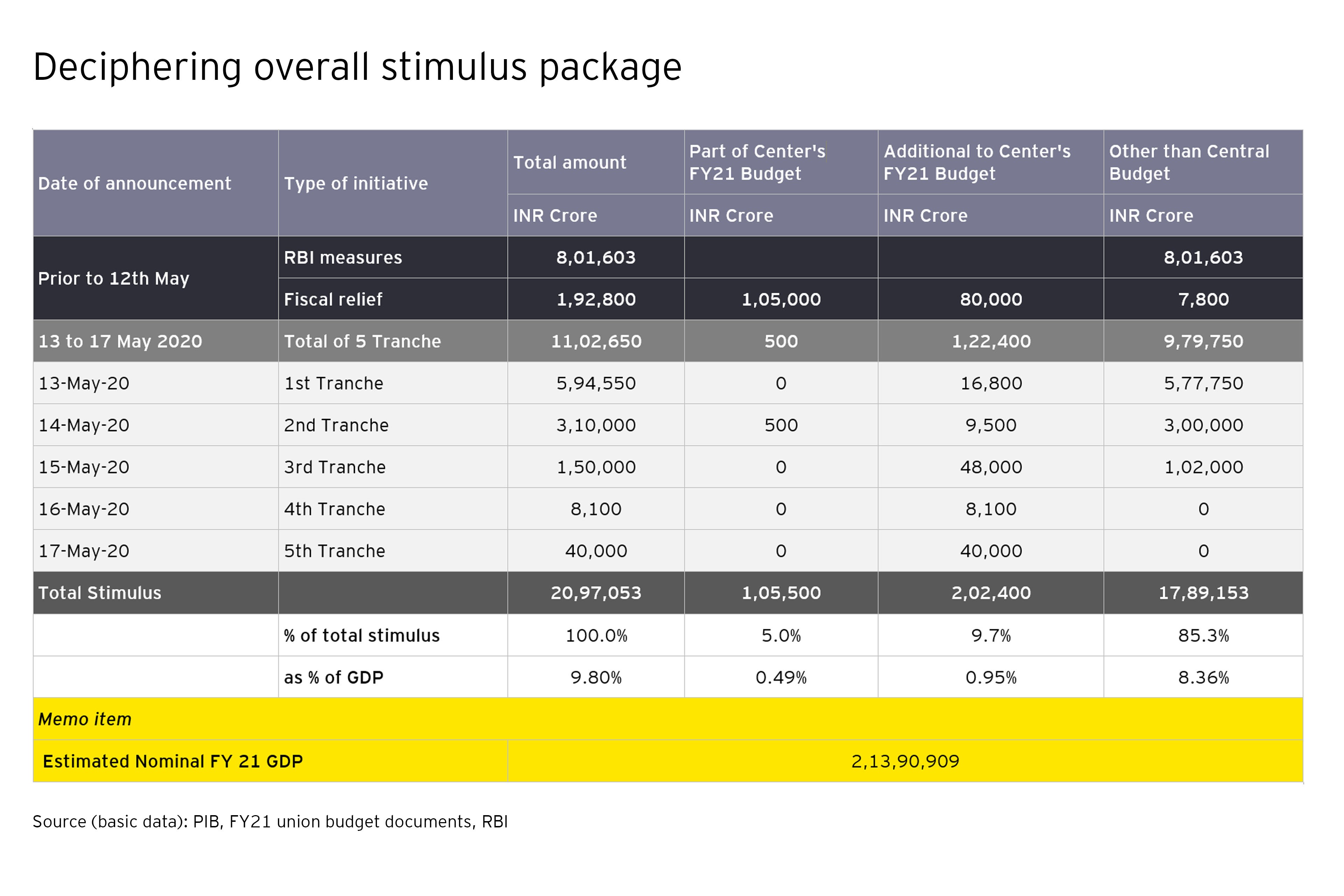

Four major sets of stimulus packages have been announced since the end of March 2020 till date. Two of these sets pertained to fiscal initiatives and two to monetary. We may describe these as follows:

- Monetary stimulus 1: On 27 March 2020, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) lowered the repo rate to a historic low of 4.4%, well below 4.75% level in April 2009, to which it was brought down in response to the 2008-09 crisis. The CRR was also reduced by 100 basis points to 3.0%. On 17 April 2020, the reverse repo rate was lowered by 25 basis points to 3.75%. Several liquidity enhancing measures were announced on 27 March 2020, 17 April 2020 and 27 April 2020. These included Targeted Long-Term Repos Operations (TLTROs) and special refinance facility for infusing liquidity into National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD), Small Industries Development Bank of India (SIDBI) and National Housing Bank (NHB) for on-lending/refinancing purposes.

- Fiscal stimulus 1: On 26 March 2020, the government announced an economic relief package of INR 1.7 lakh crores under the PM Garib Kalyan Yojana. The stimulus included insurance cover for doctors, paramedics and healthcare workers, free food grains provision and direct cash transfers through DBT for disadvantaged sections of the population. The demand side support in this package is estimated at INR 62,082 crores.

- Fiscal stimulus 2: From 13 May 2020 to 17 May 2020, the Finance Minister announced a stimulus package in five tranches which together amounted to INR 11.02 lakh crores with an additional burden on the FY21 budget of INR 1.2 lakh crores. The magnitude of first tranche was INR 5.94 lakh crores and it was largely focused on the MSME sector that is facing the maximum brunt of COVID-19. The second tranche which involved an estimated benefit of INR 3.1 lakh crores, focused on the poorer sections of the society including small and marginal farmers. It included a mix of short-term relief provisions and a scheme for affordable rental housing for migrant workers and urban poor. The third tranche containing an additional benefit of INR 1.5 lakh crores, focused on long overdue supply-side agriculture reforms. Considering the fourth and the fifth tranches together, the estimated benefit amounted to INR 48,100 crores. The fourth tranche focused largely on medium-term efficiency improving industrial reforms. Two notable features of the fifth tranche were a) enhancement of the budgeted MGNREGA allocation of INR 61,500 crores in FY21 by INR 40,000 crores and b) relaxation in the borrowing limit of states from 3% to 5% of their respective GSDPs subject to certain conditions.

- Monetary stimulus 2: On 22 May 2020, the RBI announced another reduction in the repo rate by 40 basis points, bringing it down to a historical low of 4%. Along with it, the other relevant rates such as the reverse repo rate, the bank rate and the MSF rate were also lowered by a similar margin. This should enable both the consumers and investors to borrow at a lower cost thereby facilitating an increase in both consumption and investment demand. According to information given by the RBI, the reduction in the weighted average lending rate on fresh rupee loans has been 114 basis points during February 2019 to March 2020. In the same period, the reduction in the policy rate was 210 basis points, indicating that the transmission rate stands at about 54.3%.

The stimulus package covering monetary stimulus 1, fiscal stimuli 1 and 2 amount to INR 20,97,053 crores, equivalent to 9.8% of estimated FY21 GDP. It can be decomposed into three components namely (a) amounts already provided for in the FY21 budget (5% of total package), (b) amounts that are to be additionally provided for (9.7% of total package), and (c) amounts pertaining to RBI, banks, NBFCs and other institutions (85.3% of total package).

The stimulus package covering monetary stimulus 1, fiscal stimuli 1 and 2 amount to INR 20,97,053 crores, equivalent to 9.8% of estimated FY21 GDP. It can be decomposed into three components namely (a) amounts already provided for in the FY21 budget (5% of total package), (b) amounts that are to be additionally provided for (9.7% of total package), and (c) amounts pertaining to RBI, banks, NBFCs and other institutions (85.3% of total package).