Chapter 1

The impact of aging populations on global health costs

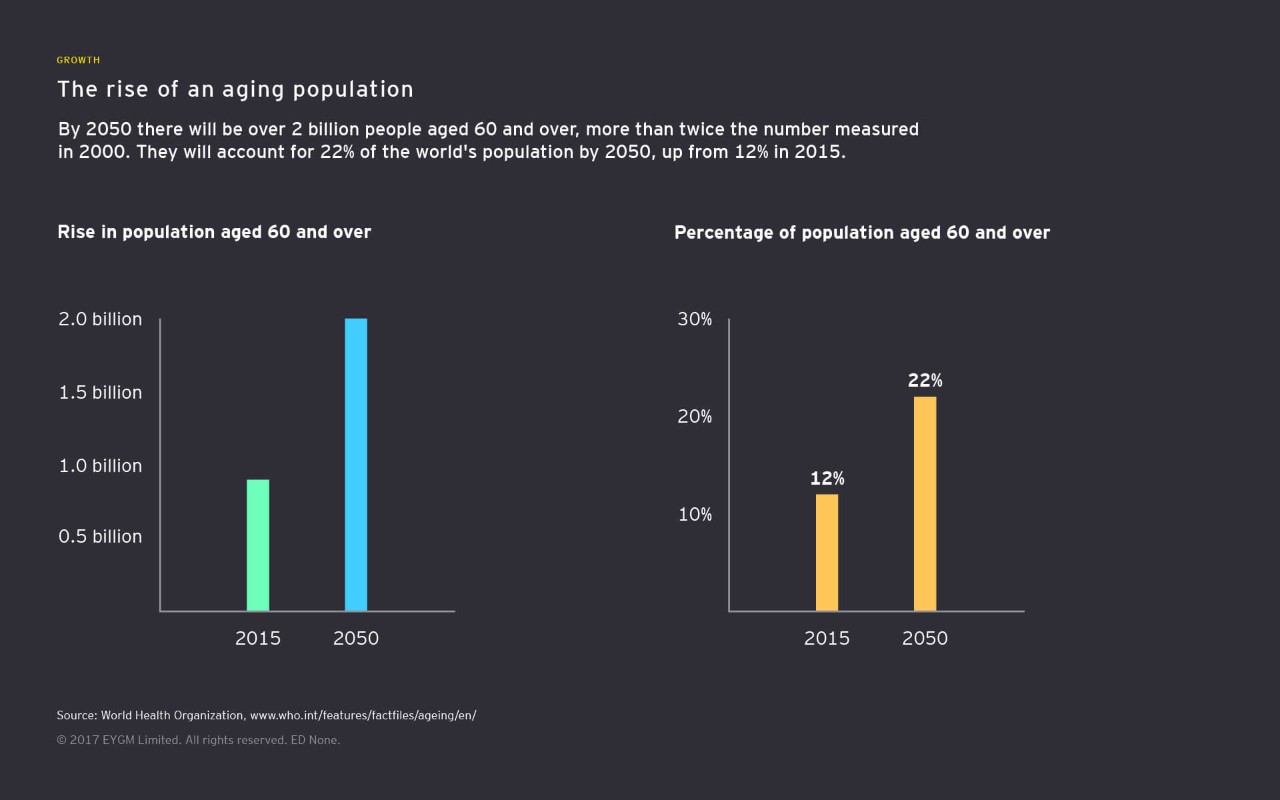

By 2050 two billion people will be aged 60 and over

The world population is aging.

- Today, there are 962 million people over the age of 60.

- By 2050, that figure stands to more than double, to more than 2 billion.

- Almost 400 million of those will be over the age of 80, and the over-65 population will have more than tripled.

These are seismic shifts with massive economic and social repercussions. For instance, by 2020, it’s estimated that 45 million US citizens (pdf) will be providing unpaid care for another adult, with more than half doing so for more than 20 hours a week.

When planning for the future, governments, businesses and individuals need to accommodate these hard facts. But treating a subject seriously does not mean being alarmist. Rather than looking at the future of aging as a burden to be borne, it needs to be seen as an opportunity to transform the way we think about old age itself — as a time of prolonged activity, engagement and wellness.

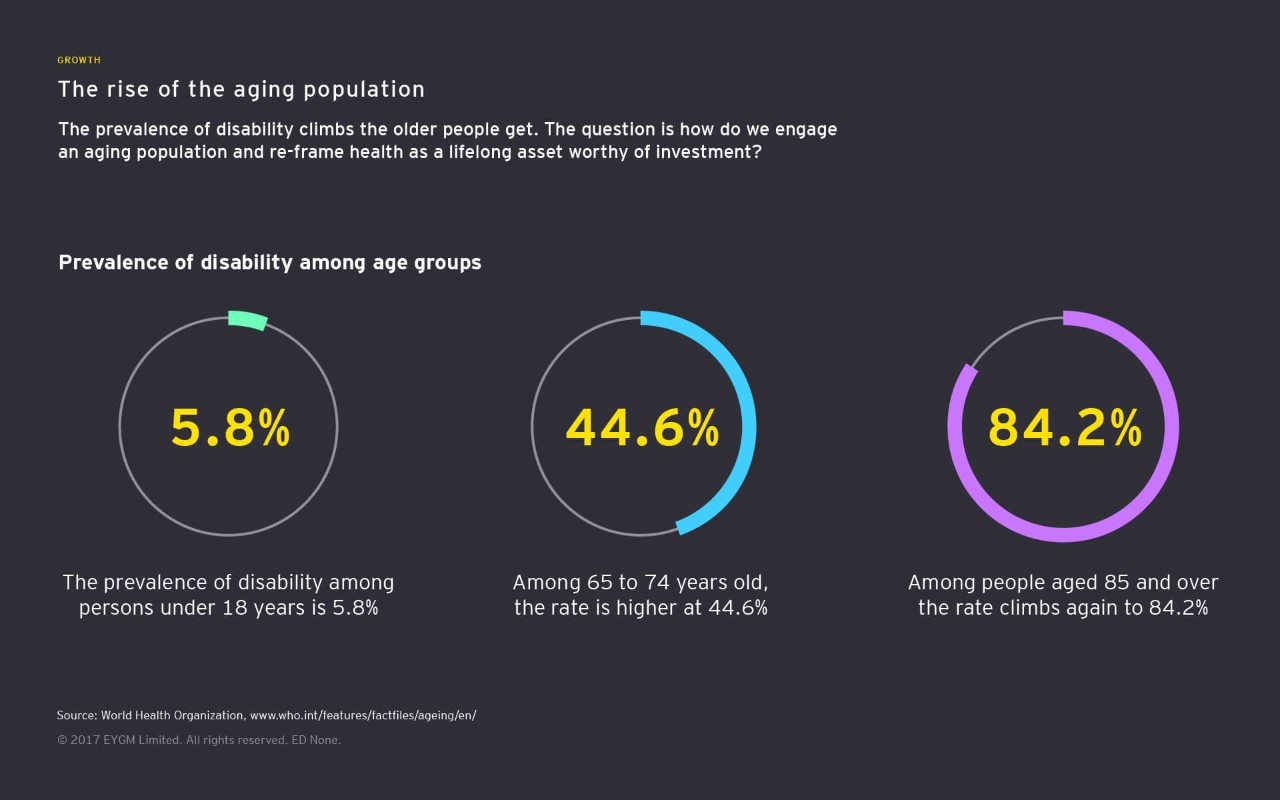

“Health must be reframed as a lifelong asset worthy of investment. This will mean looking at new technologies and innovative changes to ways of thinking and living,” says Susan Garfield, Principal, EY Global Life Sciences Consulting. If stakeholders across industries can pull together and start thinking of the challenges as opportunities, then the future of aging could be transformed in incredible ways:

- New technologies in health care and mobility will liberate the disabled and chronically ill to lead independent lives. For example, the ride-hailing company Lyft has partnered with retirement communities to provide mobility solutions to those unable to drive on their own.

- Big data and machine learning will revolutionize preventive medicine.

- Society and governments will be able to better predict and manage age-related illnesses.

- Healthier aging populations may transform the way we work and live, allowing retirement ages to be moved back and new social arrangements to emerge.

- The elderly become the “wellderly,” leading, longer, healthier and more socially fulfilling lives.

In 1952, speaking at the Boston Globe High School Press Forum, then-Illinois Governor Adlai Stevenson famously said to the students: “It is not the years in your life that count. It’s the life in your years.” Today, we need to honor that sentiment. How well we succeed will be one of our great tests over the next few decades.

Chapter 2

Technology to the rescue

Enabling the rise of "P medicine"

Solutions are on the horizon. From gene editing to exoskeletons to wearable health devices, science and technology are giving rise to innovations that are beating back the tide of chronic health issues like heart disease, cancer stroke and neurological disorders. And 70% of adults EY surveyed (pdf) in the UK, the US and Singapore said they thought tech was going to play a big role in their health as they age.

The technologies

Technology has always stood at the forefront of medical breakthroughs. From the microscopes that first uncovered the invisible world of germs and viruses to today’s cutting-edge medicines, developments in medical technology have always underpinned human health and achievement. New developments continue to come thick and fast in the digital age:

- Gene editing and genome sequencing: The sequencing of the human genome could stand as one of biology’s grandest achievements, the life sciences equivalent of the moon landing. When it was first completed in 2003, the project cost around $2.7 billion. But that number is falling dramatically. Were it to hit a figure like $100 — which some expect could happen in the not-too-distant future — it would open up an amazing range of personalized health treatments tailored specifically for an individual’s genetic makeup.

- Traditional lab development: Traditional lab methods will continue to play a central role in combating disease and developing treatment, but they could be significantly empowered by the rise of artificial intelligence and machine learning technologies.

- Multi-omics analysis: Multi-omics analysis quantifies collection of biological molecules, including the totality of proteins and genetics transcripts, and allows for more efficient analysis during medical research.

- Sensor technology: Whether worn on the wrist, attached to clothing or embedded within the human body itself, wearable sensor technology can provide researchers and caregivers with continuous streams of real-time data on the wearer’s health, opening up numerous personal development and care opportunities.

- Behavioral data: Collected from online platforms like social media networks, behavioral data could let caregivers get a more contextual understanding of a patient’s behavior and optimize care strategies accordingly.

The rise of P medicine

It’s estimated that society spends around 50 times as much managing illnesses as it does on researching ways to stop them from happening in the first place. All these strands of development could give rise to a whole new way of doing things – P health. The P stands for:

- Personalized

- Precise

- Predictive

- Pharmaco-therapeutic

- Participatory

P health isn’t a new product — it’s a new philosophy of medicine and care that looks at the long-term value of healthy populations, rather than crisis-managing illness as it emerges. The application of data and analytics to individual cases will be central to the development of P health.

Currently, medicine works based on population-level predictions. If you can predict the number of people likely to develop an illness in a given time period, you can develop the solutions to manage that risk. But if you have precise insight on every patient, then you can spot illnesses as they begin to manifest on a granular level and build improving population health care solutions from the individual up. Big data and analytics are doing for health care what the scalpel did for surgery — offering precision tools for precisions tasks and transforming the nature of aging in the process.

The challenge is going to be bringing all these together in new ways that help maximize the potential of these new technologies, potentially via a sixth “P” — new digital platforms that create seamless, data-driven health care provision ecosystems that enable more efficient and effective health outcomes than ever before.

Chapter 3

Shifting individual behaviors

How to promote positive behavioral change

P medicine, engaged aging and technology-driven mass wellness are all laudable goals. However, moving them from theory and into practice will need to involve concerted efforts from a broad range of stakeholders, from medical companies to consumers themselves.

For example, 70% of US caregivers have expressed interest in technology that makes health activities less time-intensive, but only 7% (pdf) are using solutions already on the market.

How can we close this gap? The empowered consumer is recognized as a disruptive force across multiple sectors, but how do you create empowered consumers in the medical sector in the first place?

Promoting positive behavioral change

If the medical industry’s most cutting-edge products and solutions are actually going to be used by those they are designed for, then they need to meet several criteria:

- They must have a user-centric design — people must enjoy using them.

- There must be low learning requirements — people shouldn’t be put off by complexity.

- They must immediately demonstrate apparent benefits.

- They must have the flexibility to address a variety of needs.

Additionally, if individuals are to be in control of their own health decisions, they will need access to the best data about their own performance. Wearable devices can help in providing this data, both for managing chronic illnesses and for maintaining and improving personal health, such as blood glucose sensors for diabetics and smart athletics wrist wearables.

We are moving to a world where data and algorithms that maximize health outcomes based on individual needs and preferences are the ultimate health care consumable. To create value now and in the future, data-centric business models, which are more commonly associated with online retailers, search engines and social networking sites, will provide interoperable information systems that collect, combine and share streams of data.

Such platforms can become mechanisms to connect disparate stakeholders — consumers, pharma companies, health care providers, policymakers, investors, insurers and so on — who are all driven by different incentives. Once connected, these stakeholders can share data and collaborate to combine their capabilities to drive improved health outcomes for every stakeholder group, delivered in the most cost-effective ways possible. We call the customer-focused, data driven industry that emerges from such efforts “Life Sciences 4.0.”

Nudge thinking

When designing plans and products that can help promote better consumer behavior, an understanding of behavioral economics can also help.

In 2017, economist Richard Thaler won the Nobel Prize for economics for his work on behavioral economics and “nudge” theory. Nudge theory suggests that positive reinforcement and indirect suggestions can influence people’s behavior without them being explicitly told to do so.

In one example, plastic houseflies were put in public urinals — men using the urinal would subconsciously aim for the fly and minimize splashing. Without being made aware of the end goals, their behavior was improved.

It’s no secret that when it comes to their personal health, people often need a bit of a nudge. It’s much easier to lie in bed and soak up the short-term comfort of a warm blanket than get up early for the gym in pursuit of long-term health. In behavioral economics, this is known as “hyperbolic discounting (pdf)” —rather than acting rationally, people tend to choose smaller-sooner rewards (like that nice warm bed), than later-larger ones (like the outcome of that diet-and-fitness regime).

So how can we overcome this as we build toward the future of aging? What kind of incentives can hack into our short-term gain biases and rewire us for longtime wellness as we age? Any solution looking to nudge users into positive behavior, whether coming from employers, businesses or governments, should exhibit three key features. They should:

- Highlight small behavioral changes: We are all creatures of habit, and people are resistant to changes in the status quo. Effective solutions should be based around small, incremental changes, rather than big, unsustainable programs like crash diets.

- Properly incentivize participants: Long-term wellness is an important goal, but it can be difficult to visualize. Providing people with appealing short-term rewards, like digital tokens, or constructive feedback on progress can help keep them on track to meet long-term targets.

- Recognize small improvements: Similarly, if a program only offers the long-term target, participants may be discouraged by their lack of visible progress toward that goal. By setting out smaller, intermediary goals, participants can see week-by-week how they are progressing toward greater wellness targets and take control over their own fitness journey. Program designers also need to avoid “alarm fatigue,” where users get so many prompts that they cease paying attention to any of them.

Chapter 4

A job for all stakeholders

Aligning goals for cross-industry partnership

The case for wellness is clear. Technology is becoming better and more widespread all the time. Consumer psychology can guide the creation of solutions. But in order for engaged wellness to become a truly global movement, rather than the preserve of wealthy, developed economies, these challenges will need to be addressed by stakeholders from all sectors, from medical product developers to caregivers to payers.

Unfortunately, the goals of different groups of stakeholders don't always align.

Disputes over Hepatitis C medication provide a case in point. New, recently developed treatments for the disease suggest that costs are likely to come down over patient lifetimes. However, the price of these medicines has made it unaffordable for health care payers to provide it to everyone. Drugs are expensive to develop, and developers need short-term reimbursement, but their value is realized slowly, over years. The misalignment between these two timescales means that two groups of stakeholders with the same needs are pulling in different directions.

A road map for change

Any cross-industry partnership that can seriously tackle these issues will need to be defined according to three key elements:

- Establish clear healthy aging metrics: If diverse stakeholders are to work together to the same targets, there needs to be consensus on what form those targets will take and how progress toward them will be measured. The wealth of data generated by wearable devices and sensor technology provides a strong starting point to building a foundation of universally agreed-on health care metrics.

- Sharing data and technology: Data and technology will play a central role in realizing health aging objectives. But currently, many of these assets are siloed by companies careful to preserve their intellectual property. Why should a company share designs for its heart monitor with a competitor? There is certainly a risk from such open collaboration and sharing — but there is also a risk from doing nothing. The benefit is the division of R&D costs and the creation of innovations that can only come from collaboration and industry convergence. Collaboration could uncover new opportunities for improved customer experiences, expanded offerings and even new payment models that benefit the entire health sector.

- Government involvement: The burden of aging populations will fall heavily on governments around the world, so those governments have a clear interest investing in healthier future. They are also well-positioned to set the conditions in which healthy aging initiatives can flourish, such as by sponsoring the development of public-private partnerships.

Getting this right can drive real gains in realizing long-term wellness goals. In 2012, a group of California-based payers, providers and employers started a public-private partnership, AIM4Fresno, with the investors Collective Health and Social Finance to demonstrate that comprehensive home-based asthma management could yield financial and social benefits in Fresno, California. An analysis of the small number of participants who completed the one-year program showed net savings from reduced health care costs of approximately US$2,200 per person over 24 months.

More value like this is waiting to be unlocked if government and public sector stakeholders can learn to work toward shared goals and share resources and data. But it will need commitment and drive if society is to reap the rewards of engaged aging and engineer a future in which people’s twilight years are also their most enriching and fulfilled.

Summary

Government and public sector stakeholders need to work together to generate true value from engaged aging.