EY refers to the global organization, and may refer to one or more, of the member firms of Ernst & Young Global Limited, each of which is a separate legal entity. Ernst & Young Global Limited, a UK company limited by guarantee, does not provide services to clients.

How EY can help

-

Discover how EY's Supply Chain Transformation solution can help your business move towards fully autonomous, connected supply chains that drive business growth.

Read more

Geopolitical risk, tariff and trade change combined with a radical review of the product portfolio and bill of materials may reveal products that — regardless of their manufacturing location — are no longer profitable to make and sell in certain geographic markets, or at all. If a manufacturer is unable to pass on inflationary costs such as tariffs or cannot produce a particular product sustainably, some products may become obsolete.

For some, trade tariffs may be the tipping point – and they have been a trend for some time already. According to Global Trade Alert1 the number of trade interventions has increased more than 200% over the past five years and almost 400% over the past decade. Many of these trade barriers have been put in place by governments seeking to strengthen their country’s economic security, with the current US tariff policies increasing the urgency and significance of these actions.

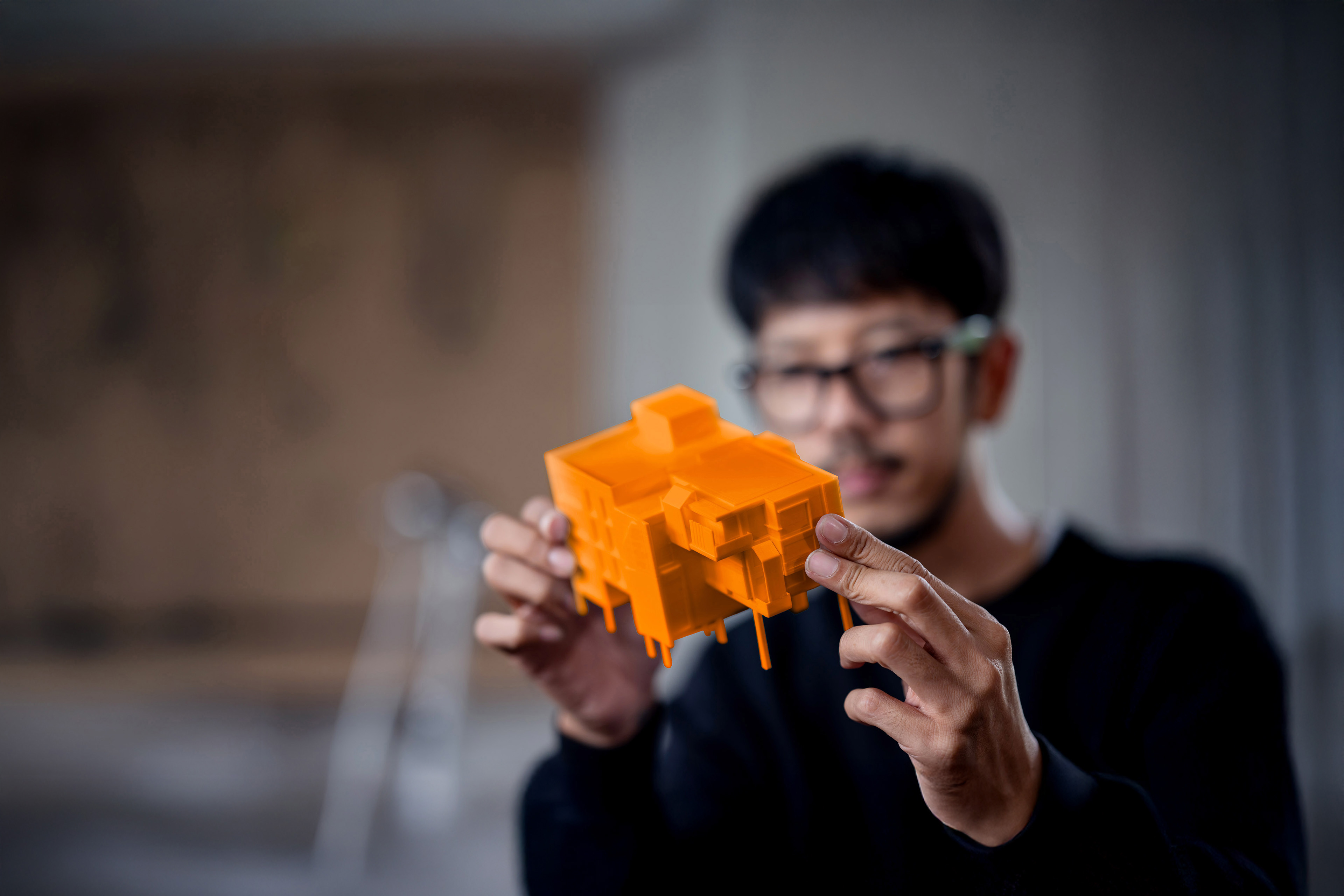

Leading companies are using product tear down and cost modeling together with product and bill of material (BOM) value engineering to both rationalize the portfolio and BOM complexity. Companies are also reworking BOM items to find alternate suppliers or different materials with different suppliers to reduce the total delivered cost – including rules of origin and tariff impacts.

And in many sectors, the cumulative effects of the rising costs of products and reduced working capital, logistics, carbon charges for border crossings, and frequent supply disruptions are increasing the cost-to-serve, reducing gross margins and making it unprofitable to hold inventory as a buffer.

These dynamics have forced a focus on whether to enter or exit certain geographies. For example, in a tariff-dominated world profit potential may be low or opportunistically high in certain geographies, or companies may be less exposed than their competitors in different geographies. This could drive specific action on exiting or entering certain markets. Some political programs are also steering companies to more local supply chains, effectively taxing those that fail to move this direction, and tax-incentivizing those that do move. These dynamics are at the core of designing more segmented footprints.