Chapter 1

A step change is needed in efforts to tackle the climate crisis

Economic growth can no longer be pursued at the expense of climate change and environmental degradation.

Plastic flowing into the oceans is expected to nearly triple in volume in the next 20 years, adversely affecting our ecosystems, health and economies.4 And the UN estimates that agricultural production will need to increase by about 50% by 2050 to keep pace with rising demand for food.5 But food systems cause as much as a third of greenhouse gas emissions, up to 80% of biodiversity loss and use around 70% of freshwater reserves.

Market forces alone won’t solve the problem, and the onus is on governments to take a lead.

The scale of action required cannot be underestimated. It requires a fundamental transformation of all sectors, including energy, manufacturing, transport, infrastructure, agriculture, forestry and land use. Humans must also radically rethink how we produce and consume food and fuel and manage waste.

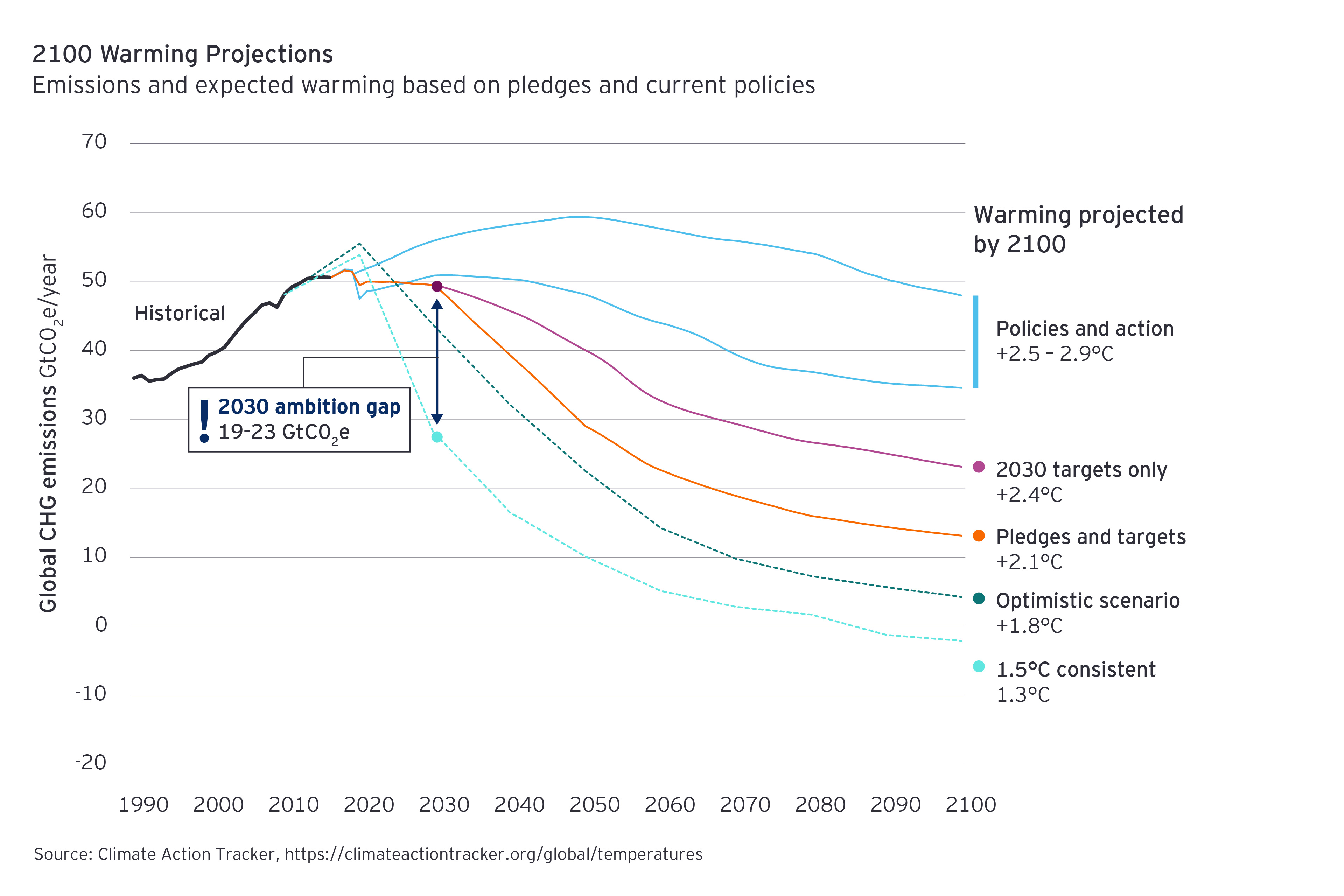

Market forces alone won’t solve the problem and the onus is on governments to take the lead. Many have set targets — some enshrined in law — to achieve net-zero carbon emissions by specified dates (from as early as 2030 in Uruguay and 2035 in Finland to 2050 for most other countries).6 Crucially, the world’s two biggest emitters, the US and China, have both committed to carbon neutrality by 2050 and 2060 respectively. The EU is also setting the pace with a new set of policies to achieve its sustainability goals: the EU Green Deal and Climate Law set binding targets to cut emissions by 55% by 2030 (from 1990 levels) and to reach climate neutrality by 2050.

Chapter 2

Governments must step up to meet the sustainability challenge

Despite many available tools for addressing climate change, government efforts are falling short.

Governments can choose from a wide range of policy interventions and financing measures to support the transformation of energy and industrial systems, improve energy efficiency, tackle environmental pollution, and protect and replenish natural capital.

Many are adopting a stick and carrot approach, including green taxes on harmful environmental activities, tighter regulations, and new environmental standards and certification for energy performance, emissions and pollutants – including tax rebates for meeting these standards. We also see many examples of loans and grants for green investments in sustainable agriculture, renewable or low-carbon energy sources, energy-efficient buildings, public walkways and cycleways and electric vehicle (EV) infrastructure.

Subsidies and tax rebates are additional tools to boost demand for green products and services like EV, solar panels or renewable energy. Governments are also offering subsidies and grant funding to research institutes, academic institutions and private R&D firms to boost innovation and develop transformative technologies such as renewable energy, carbon capture, waste management, and energy efficiency.

Germany committed €2.5 billion for investment in EV infrastructure. In Shenzen, China, the three major bus operators were incentivized to transition to EV through an annual subsidy of USD 75,500 for each vehicle. And in Vietnam, installations of rooftop Solar PV capacity have increased by 2,435% since 2019.

Germany committed €2.5 billion for investment in EV infrastructure and a €9,000 subsidy per vehicle to encourage adoption. In Shenzen, China, the three major bus operators were incentivized to transition to EV through an annual subsidy of USD 75,500 for each vehicle. And in Vietnam, installations of rooftop Solar PV capacity have increased by 2,435% since the beginning of 2019, driven mainly by a feed-in-tariff scheme.7

Then there’s direct public investment in nature-based solutions and agriculture to protect nature’s ecosystems and create a sustainable food system — including afforestation, wetlands restoration, wildfire prevention and water irrigation. The Pakistani government, for example, has earmarked between US$800 million and US$1 billion over the next four years for an afforestation program to capture carbon while also creating job opportunities for thousands of low-skilled workers.8

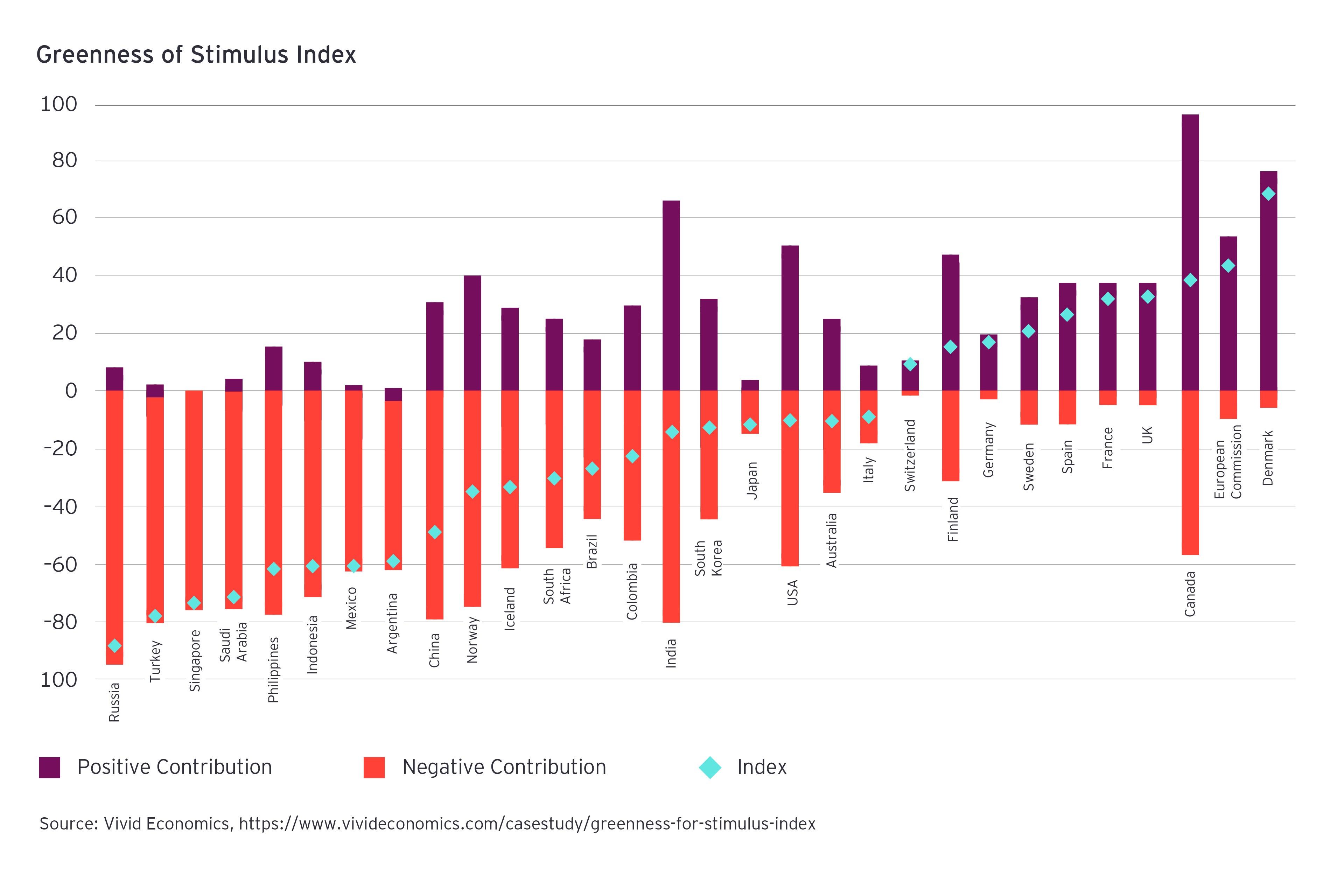

The massive COVID-19 stimulus packages provide an opportunity for countries to incorporate these measures into their recovery plans — returning their economies to growth while meeting environmental goals. For example, funding from the EU Commission’s Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) is contingent on climate goals, demanding at least 37% of countries’ expenditure on green initiatives. Similarly, the US Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act provides US$1 trillion for investments targeting sustainability.

However, green stimulus measures fall well short of what’s needed. The Greenness of Stimulus Index assessed the environmental impact of US$17.2 trillion of stimulus across 30 countries and found more negative than positive environmental policy interventions.9

Additionally, the 2020 Sustainability Leaders survey from GlobeScan (pdf)10 concluded that national governments lacked leadership on sustainable development – further evidence of the need for more decisive state interventions to tackle the increasing global sustainability challenges.

Pioneering the surge towards sustainability

Business has the influence and levers of change to help create actionable outcomes and impact. As we note in this report, high performing companies are increasingly recognizing that paying attention to the longer term, to stakeholder perceptions, and to the social and environmental consequences of their products is good for business as well as the planet. The GlobeScan (pdf) study highlights those private sector organizations and NGOs leading the way. Their achievements are based on integrating sustainability into their core business model, setting ambitious targets and a clear commitment to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

Universities are also setting a positive example, such as The University of Tasmania, which ranked third in the world in the Times Higher Education university rankings for climate action. By closely auditing, reducing and offsetting its emissions, it’s been carbon neutral since 2016.

Citizens can also play a big role, exemplified by the Weather Chasers Group in Malawi, which has become a dynamic force for environmental protection (such as tree planting events) and part of a larger civil society movement for positive change — influencing government policy.

What’s holding governments back?

A number of factors are preventing governments from realizing their sustainability ambitions:

- Political short-termism: Despite much political rhetoric pledging change, governments are often swayed by public opinion, populist media and short-term political cycles, which can derail policies to address complex, longer-term challenges. Without defined budgets, policies, regulations or detailed sector plans and targets to underpin pledges, it’s hard to evaluate progress.

- Competing priorities for policies and funding: The COVID-19 recovery is putting a further strain on public finances already challenged by record levels of debt. This may reduce funds for green investments and change donor organizations’ priorities on climate action. Siloed cultures can also hinder cooperation between government departments, with conflicting aims preventing a coordinated environmental effort.

- Economic pressures and industry lobbying: Many governments are under pressure to preserve established carbon-intensive or “brown” industries, such as airlines and manufacturing, which are strategically important and account for a significant share of jobs and GDP. G7 countries have allocated more than US$189 billion of recovery funds to support fossil fuel industries,11 and some business lobby groups are even urging a rollback of environmental protections to stimulate economic recovery. The Federation of Korean Industries argues that manufacturing plays a large part in production and employment and that a drastic carbon reduction target could impede efforts to create jobs and encourage economic vitality.12

Related article

The Federation of Korean Industries argues that a drastic carbon reduction target could impede efforts to create manufacturing jobs and encourage economic vitality.

Similarly, the US government instructed agencies to prioritize economic recovery by waiving or exempting polluters from any regulations or requirements which might inhibit their progress.

- Poor planning and implementation: Governments must create the right conditions for sustainability and some initiatives have failed to take account of key dependencies. In the UK, for example, the failure of the government’s Green Homes scheme has been attributed to rushed design and implementation. Lack of engagement with the industry, coupled with the scheme’s short duration, made it hard for energy efficiency installers to mobilize to meet demand.13

- Lack of priority and transparency from governments: The UK’s National Audit Office surveyed Audit and Risk Assurance Committees across government to gauge climate change risk maturity. Although four out of five considered climate risks to be relevant to their organization, over half had no climate or sustainability risk policy nor a dedicated accountable employee.14 And while reporting on environmental, social and governance (ESG) issues has become more common in the private sector over recent years, sustainability reporting in the public sector is in its infancy. An international survey of public sector organizations shows that more than half (56%) do not currently report on their climate impact.15

Transparency

56%of public sector organizations do not currently report on their climate impact

- Insufficient public engagement: Many governments have not sufficiently engaged with the public to educate them about environmental challenges. Lack of understanding has contributed to inertia in changing consumption choices or behaviors. More than one-third of respondents to the 2020 Ipsos Global Trends survey said they were "tired of the fuss that is being made about the environment."16 There has also been strong opposition to policies that push decarbonization costs onto consumers, such as the "Gilets Jaunes" protests against the carbon tax in France.

- Disruption to global energy supplies: The war in Ukraine has created contradictory forces that make the green energy transition even more challenging. Simultaneously, countries are pledging to reduce carbon emissions while advocating for increased fossil fuel exploration to satisfy immediate energy needs and reduce dependence on Russian oil and gas.

- Lack of global leadership and cooperation between countries: COVID-19 highlighted the general lack of collaboration between countries in tackling global crises and exposed weaknesses in multilateral organizations. The geopolitical impact of the war makes international cooperation all the more challenging.

Early efforts to agree on a collective response to the climate emergency have fallen short. For example, carbon markets – which allow countries and companies to buy credits to meet their climate goals by investing in carbon-cutting projects elsewhere - have long been touted as a cost-effective way to reduce emissions. After six years of wrangling, the UN-led effort to create a market for units representing emissions reductions under the so-called Article 6 was finally agreed at COP2617, 18 .More support for developing countries most impacted by climate change and least able to afford its consequences, will be vital. But the final COP26 agreement notes with “deep regret” that rich countries missed their 2020 target of providing US$100 billion a year to help developing countries.

Chapter 3

A multi-sector effort to close the climate funding gap

The private sector has a critical role to play but needs to be better incentivized to play its part.

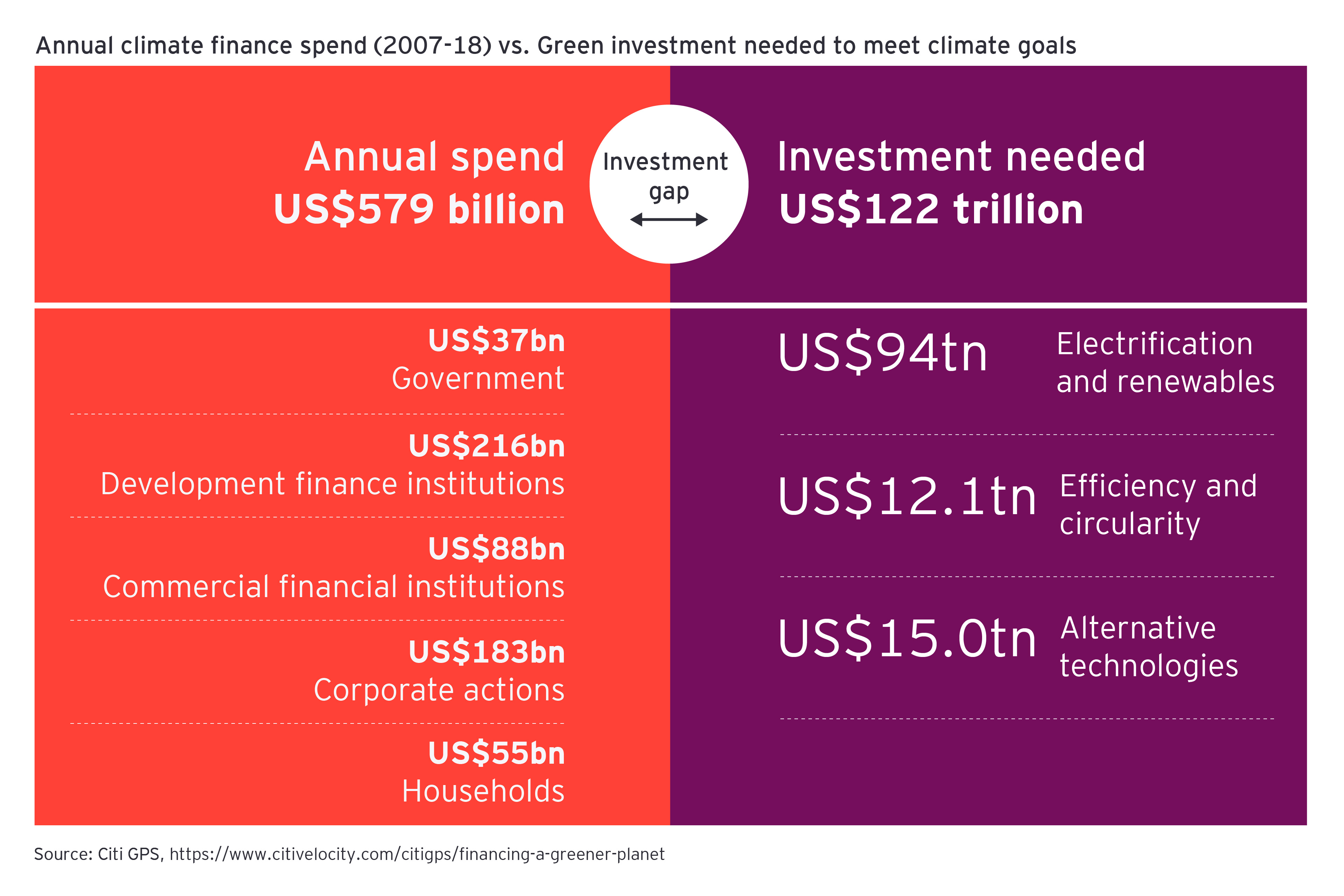

Tackling the sustainability challenge requires significant investment going far beyond current levels. According to Citi, the gap between actual and necessary climate crisis spending is US$3-US$5+ trillion per year.19

Implementing the pipeline of shovel-ready renewable energy projects would inject more than US$1.9t into the global economy over a three-year period.

Public funding alone will not be enough, so governments must encourage investment from multilateral organizations, financial institutions and the corporate sector. The good news is that ESG has risen up the corporate agenda, with institutional investors increasing their interest in areas such as renewables and e-mobility. Moreover, capital is abundant and there is a strong pipeline of growth-inducing green projects awaiting investment. Implementing the pipeline of shovel-ready renewable energy projects would inject more than US$1.9t into the global economy over a three-year period, equivalent to 85% of the GDP lost in 2020.20

What’s holding private investors back from green projects?

- Regulatory and policy uncertainty: Uncertainty raises project revenue risk, which in turn, reduces project viability, investment, private sector interest and innovation. Institutional investors also face significant bureaucracy and onerous reporting and disclosure requirements — such as demonstrating that investments satisfy regulatory criteria.

- Poor incentives: Many green technologies have large upfront R&D costs and long and risky development periods but only generate long-term payback. And the potential for knowledge spillovers means investors only earn a fraction of the total rate of return as benefits also accrue to other companies.

- Small, fragmented markets: Investors are not always confident in recouping large, risky up-front investments in R&D or new production capacity if the end market is small.

- Lack of market data: Without robust data, it can be hard to assess the expected risks and benefits of investment — especially for smaller start-ups and new innovations. This can push up the cost and may limit access to external finance.

- PPP failures: Private-public partnerships can fail to deliver due to ill-defined outcomes, insufficient private sector capacity, and lack of expertise and experience among both private and public players. These can lead to poor planning, implementation delays and project failure.

- Unclear investment goals: With a lack of globally agreed principles for climate finance, investors struggle to align investments with climate goals. The EU has been the most progressive with its sustainable finance taxonomy, which aims to support sustainable investment by clarifying the economic activities that most contribute to meeting EU environmental objectives.21

Chapter 4

Six government priorities for accelerating the green transition

Overcoming economic, political, regulatory and financial obstacles requires a bold, coordinated approach sustained by long-term commitment.

The actions governments take now could set the world on a path to a more sustainable future that balances environmental, economic and social outcomes. But the clock is ticking, and rapid progress demands priorities:

- Provide detailed action plans with clear accountability

- Be bolder in incentivizing the market and mandating change

- Boost innovation through increased funding

- Improve the design and delivery of green initiatives

- Act as a role model for other parts of the economy

- Promote a whole-of-society, people-centered approach

Provide detailed action plans with clear accountability

Detailed, sector-specific road maps, produced in collaboration with industry, can bridge the gap between long-term pledges and short-term action plans with measurable targets. These should set out specific policy measures and initiatives, desired outcomes, timelines, and necessary resources. By publishing these plans, governments can broadcast how they are working towards environmental goals and set out the roles of the main players.

The delivery of a green action plan goes far beyond the remit of energy or environment ministries. It becomes an intrinsic part of policy across all governments’ activities, from infrastructure, housing, transport and defense, to education, health and social services. It’s likely that other policies or priorities may conflict with climate goals, so a clear vision and a holistic plan are essential to align all departments’ efforts to achieve shared goals.

A single entity, either new or existing, should have oversight over delivery to help ensure a coordinated, whole-of-government approach across diverse sectors. This team can manage cross-departmental initiatives, identify synergies and dependencies, anticipate potential issues and take corrective action if necessary.

Local and regional governments play a vital role in implementation, so should be engaged in policy design from the outset and given the necessary powers and resources to deliver green initiatives. Local governments, for example, will be heavily involved in housing retrofits and creating EV infrastructure and can also deliver pilot projects before scaling up nationally. However, global research from the Climate Group shows only 21% of 121 states and regions surveyed had been consulted on national climate action plans.22

Collaboration

21%of 121 states and regions surveyed had been consulted on national climate action plans by their national counterparts by the end of 2020.

Finally, governments will need to monitor the implementation of their action plans. This requires a baseline and clear, consistent measures to monitor status and report on progress — internally and externally. The measures must reflect the contribution of public, private and third sector entities to maximize accountability for results.

Be bolder in incentivizing the market and mandating change

The urgency of the environmental challenge calls for ambitious policies that prioritize climate action and send a clear message about how the market and citizens can achieve radical change. Only through a strong political will can governments overcome opposition and build cross-sector support.

Policies such as incentives and penalties encourage businesses to align investments and economic activities with climate goals. To accelerate decarbonization, for example, some governments are phasing out subsidies for fossil fuel industries. Others are implementing carbon taxes and emissions trading to ensure the prices of goods and services accurately capture the social value of the natural resources used in their production and to make renewables more cost-effective. As well as penalizing carbon emissions, carbon taxes provide additional revenue for governments. According to the World Bank, in 2021, 64 carbon pricing initiatives had been implemented globally, covering 45 national jurisdictions and 21.5% of global emissions.24

In parallel, governments and regulators need to mandate effective carbon accounting for businesses to capture direct and indirect emissions across supply chains, as well as common, mandatory reporting standards to track environmental impact. In November 2021, the International Financial Reporting Standards Foundation announced the formation of the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) by June 2022, and publication of prototype climate and general disclosure requirements. In the US, the Securities and Exchange Commission is moving towards mandating corporate disclosures of exposure to climate risk, while the UK government is set to enshrine in law a requirement to report on climate-related risks and opportunities.

Canada’s federal carbon tax is expected to raise petrol prices by around 8%, natural gas by 50%, and coal prices by 100%. Approximately 90% of the revenue from the tax will be rebated to consumers to encourage a switch to low-carbon consumption.

Some governments have taken a stronger environmental stance by removing subsidies for carbon-intensive sectors or making bailouts dependent upon environmental performance or commitments. Air France, for example, is required to reduce emissions by 50% and achieve a minimum standard of 2% renewable fuel by 2030 as conditions of its rescue by the French government.

Other governments are passing legislation to ban environmentally harmful energy or mandate green energy. The French government has banned gas heating in new houses, while in the Indian City of Chandigarh, larger properties are required to have rooftop solar panels, which have generated more than 30MW of solar power since 2019. India’s "Development of Solar Cities" scheme, which covers up to 60 cities, insists on solar water heating systems in certain categories of buildings, as well as providing financial and technical assistance for increasing renewable energy and energy efficiency. Meanwhile, in the US, 30 states have passed renewable energy portfolio standards, requiring electricity suppliers to give customers a stated minimum share from clean sources. A proposed national policy was still awaiting approval in late 2021.

Several governments have taken stringent measures to ban polluting products outright. Plastic, which accelerates climate change by emitting greenhouse gases at every stage of its lifecycle, has been a particular target. Rwanda became the world’s first "plastic-free" nation in 2009, 10 years after introducing a ban on all plastic bags and plastic packaging. In May 2021, Canada declared plastic a "toxic" substance, paving the way for its proposed ban on most single-use plastics by the end of 2021.25

Boost innovation through increased funding

To meet climate goals, governments have at their disposal a range of policy instruments to accelerate public and private investment in new infrastructure and new technologies — including development and early-stage demonstration projects.

Shortfall in project funding

US$90 billionof public money is needed globally to complete a portfolio of demonstration projects before 2030.

According to the International Energy Agency, around US$90 billion of public money is needed globally to complete a portfolio of demonstration projects before 2030. But only around US$25 billion is currently budgeted — leaving a huge funding gap.26

A mission-driven approach to public sector research and innovation can help governments target their funding more effectively. This involves investing in a portfolio of initiatives with specific objectives and bringing different sectors and public, private, and third sector actors together to innovate.27 Rather than blindly trying to pick winners, governments can bring together researchers, scientists and climate experts to advise on which technologies are ready for deployment or development, as well as potential new technologies to research. Continuous monitoring and evaluation of pilot projects should swiftly identify projects that can either be scaled up or withdrawn.

As well as increasing public funding, governments can stimulate more private involvement in R&D by creating an appropriate policy framework and enabling environment that helps to lower risk and unlock the full potential of private investment. For example, flexible regulations reflecting the uncertainty of new technologies can speed up innovation, while governments can also intervene to create alternative markets, break up monopolies, open up competition and encourage entrepreneurship.

Clearer commitments from governments on infrastructure spending — and details of pipelines of relevant investments likely to be supported — would help increase funding opportunities and provide long-term stability for institutional investors and insurers. The Japanese government is funding renewables to reduce dependence on fossil fuel imports and to shift from nuclear following the 2011 Fukushima disaster. A 2019 bill permits wind farms to operate in Japanese waters for up to 30 years, signaling a commitment to wind power.

Many national and regional governments have established publicly capitalized, commercially oriented green investment banks. They attract private investment for climate-friendly, sustainable projects by breaking down barriers and carrying some of the economic and political risks that can stifle green investment. The banks tap into new sources of domestic capital (e.g., pension funds) and international capital (e.g., from development banks). According to a 2020 report, green banks have an impressive track record in catalyzing new low-carbon markets and drawing private investment, having invested US$24.5 billion of their own capital since their respective inceptions.28

Governments must also create the conditions for private businesses to raise long-term funds in areas where financial organizations are not yet willing to make sufficient investments. Solutions- include structured finance tailored to specific sectors and mechanisms and policies that mitigate risks or allocate them appropriately to different parties. For instance, in the renewable energy field, feed-in tariffs and quota schemes have helped drive growth in wind power and solar programs. And there’s growing interest in "contracts for difference" agreements, which incentivize investment in renewable energy by reducing price volatility, making future revenue streams more stable and predictable.

Policy measures such as low interest rate financing reduce risks for investors, buying time to scale up technologies and programs and achieve longer-term financial sustainability. Governments can also deploy tax incentives, favorable lending and sustainable finance like green bonds or sustainability-linked loans. But, as our recent report on the flows of green money concludes, the financial sector should direct more funding towards green initiatives.

Climate finance taxonomies and other classifications will also help align investments with climate goals. No single taxonomy can meet every need, but government policymakers, regulators and market participants should agree on global guiding principles to be used across regions.29

Improve the design and delivery of green initiatives

Governments must carefully consider the design and implementation of green initiatives to avoid the risk of failure. Like all major government programs, they require a clear vision, realistic timescales, appropriate funding and a supportive regulatory environment. But success also depends on having the right resources to deliver — in terms of workforce skills and supply chain capacity — and consulting with industry and other key stakeholders to identify other critical dependencies and barriers to change.

Adopting a “whole systems approach,” based on cross-government and cross-sector coordination, is critical to take into account the broader context. It can help governments better understand the complex factors that could affect the program’s outcome, including constraints or pressures in the system, and develop solutions to mitigate problems (for example, encouraging businesses to develop capacity). It also provides a means to identify important synergies, interdependencies and trade-offs between green strategies and other policy priorities (like industrial growth, citizen convenience, etc.), to understand the key levers, and when to intervene.32

One key challenge has been the need for better data and insights to create a coherent overview of the whole system. But advances in integrated systems and sophisticated analytical tools are now helping governments capture and share information to enable seamless interactions and inform decision-making. Policies can be co-created and monitored, with regular communication and reporting, flagging when to act.

In addition to planning and coordination, governments must anticipate increased demand for new types of skills and know-how to deliver on green initiatives. Targeted funding and a national green skills plan can help map out the quantity and type of skills needed, where new “green jobs” should be located (to ensure that no regions are left behind), and how to invest in education and retraining. In the US, the Department of Employment plans to invest US$30 million in training workers to build high-performance buildings making use of renewables, efficient lighting and better management of energy.36

In the UK, organizations across sectors crucial to the green transition have been warning of difficulties in sourcing people with the right skills. The non-profit Generation UK has teamed up with private finance group Macquarie to run a new training program for unemployed young people to provide the skills they need to thrive in jobs within the green sector. It has set a target to place 80% of learners into roles within three months of completing the training and is actively onboarding employer partners.37

Act as a role model for other parts of the economy

The public sector itself is a significant contributor to climate change and environmental harm as providers of services and consumers of resources. To set an example, governments should compel departments to put a stronger emphasis on identifying and mitigating the environmental impacts of their activities.

All public entities should monitor and publish carbon emissions, embrace carbon offsetting and removal, decarbonize the vast estate of public buildings, and electrify public vehicle fleets. The US federal government is the country’s single largest energy consumer, with more than 360,000 buildings representing almost 60% of the government’s energy use. It has announced plans for building performance standards for all federal facilities,38 while the Department of Energy has developed an "efficient buildings roadmap," based upon solar and wind power, and demand management and storage.39

Reforming public procurement can have a dramatic impact. By setting strict green criteria for contracts, governments can improve their own carbon footprint through the use of greener products and services while encouraging other actors to improve their own sustainable consumption and production practices. Governments may have to overcome negative perceptions (for example, that green products and services are more expensive), and will certainly need to train public procurers, sustainability officers and project managers in sustainable procurement.

Governments can set the pace for sustainability reporting by highlighting the environmental impact of their spending. Efforts will need to be made to harmonize the multiple existing frameworks for sustainability reporting and tailor them for public sector needs. Through advanced data capture and analysis, governments can enhance their impact monitoring and reporting, at the same time upskilling staff with appropriate data capabilities. Mandatory reporting creates a sense of urgency, and independent third-party organizations, including national audit offices, should audit reports and recommend improvements.

The Nordic countries are emerging as leaders in sustainability reporting. Finland’s State Treasury published new guidance in September 2021, recommending that all ministries, agencies, and institutions produce an annual sustainability report on their societal and global impacts.40 The municipality of Herning in Denmark has voluntarily released "green" accounts since 2012. These cover procurement, recycling and waste, nature and green areas, municipal properties, planning and private construction, transport and energy consumption.41 The initiative has been given added impetus by the DK2020 project, which supports 20 municipalities in developing, upgrading or adjusting climate action efforts, in line with the Paris Agreement goals.42

Promote a whole-of-society and people-centered approach

The huge and complex challenge of climate change inevitably demands collaboration from every individual and organization across society. The initial momentum for the energy transition in the Netherlands, for example, started in 2013 with the Energy Agreement for Sustainable Growth, bringing together government, industry, trade unions and the third sector to shape the country’s plans. Over time this led to the country’s national climate commitments in 2018, again working with labor unions, NGOs, business associations and local authorities to confirm targets.43

Citizens have a crucial role to play in tackling climate and environmental problems by changing their behavior and informing policymakers of their views. Research shows that people are willing to make changes in their own lives if they see this as part of a wider national effort to cut emissions.44 More participatory forms of public engagement, such as online deliberation and citizens assemblies, help involve people in problem-solving and climate action policy. An analysis of climate assemblies in France and the UK suggests citizens generate far more ambitious policies than politicians, having a significant and immediate effect on climate policy.45

Governments can also do more to educate people on the impact of their lifestyle choices, nudging them towards more sustainable consumption and behavior — such as ethical investment, electric vehicles, retrofitting homes or changing diets. Researchers from INSEAD and the University of Southern California surveyed a wide range of behavioral experiments linked to green issues, concluding that nudges don’t just promote eco-friendly behavior; they may also be more effective than government communications.46

But there can be no one-size-fits-all approach for citizens. Meeting climate goals brings costs for all individuals, whether as taxpayers, billpayers, shareholders, workers in carbon-emitting industries or consumers of carbon-intensive products. The poorest households, where energy bills are a higher proportion of household spending, often suffer the most from the transition in terms of higher fuel prices and costly conversions.

A "just" transition can ensure that costs and benefits are fairly distributed. This requires government investment and support, including subsidies and exemptions, and careful targeting of interventions to avoid adverse outcomes. Such policies could generate social and economic benefits that reduce poverty and address gender, health and economic inequalities.47

Finally, governments cannot ignore communities who stand to lose out from the green transition, such as coal miners and oil workers. Support will be needed to diversify the economy in regions where jobs or livelihoods are at risk and to help provide new green employment opportunities. The UK’s Humber region has become a "cluster" for offshore wind, helping revitalize the region after a period of economic decline. The area is now home to six operational offshore wind farms, with a range of new jobs in renewable energy plants, as well as manufacturing and other high-skill positions.

Related article

Final thoughts: cracking the code for the green transition

Governments acknowledge the need to grow sustainably but, with a few exceptions, have yet to achieve the momentum to align all their agencies, private sector players, NGOs and citizens behind a coherent plan.

Given the gargantuan efforts required, prioritizing is essential to best harness scarce resources and make the most efficient use of finite funding. Studying and adapting the efforts of others can shorten the learning curve, and some of the examples in this report can serve as useful lessons on how to overcome significant obstacles.

Collaboration is vital, with every part of society having to contribute, from individual citizens to development banks and multinational corporations. Meeting the Paris Agreement targets also calls for international coordination; in a connected world, every action has global consequences, with most supply chains reaching beyond national borders. But this requires better leadership from developed countries’ governments and multilateral institutions to strengthen international legal frameworks governing environmental matters, and to provide the necessary funding and technical assistance to less developed nations that are most at risk.

COP26 has delivered some hard truths on how far there is to go. Still, through innovation, allied with solid, unwavering commitment, the world can deliver on its promise of sustainable growth that benefits the planet and all who inhabit it.

Summary

Governments in every country recognize the need to accelerate the green transition. However, creating new green pathways will require long-term commitment, increased investment, continuous innovation and collaboration between government agencies, the private sector, NGOs and civil society.