EY refers to the global organization, and may refer to one or more, of the member firms of Ernst & Young Global Limited, each of which is a separate legal entity. Ernst & Young Global Limited, a UK company limited by guarantee, does not provide services to clients.

EY’s analysis of recent climate transition plans: optimistic assumptions, imperfect transparency, and our recommendations for greater credibility.

In brief

- In current climate transition plans, EY observes a heavy reliance on overly optimistic assumptions, as well as a lack of transparency on the uncertainty of emissions reductions.

- Companies can improve the credibility of climate transition plans by using scenario analysis to develop ranges for emissions and funding estimates.

- Organisations should act now to mitigate the risks of missing targets, reputational damage, and unforeseen decarbonisation costs.

Developing a credible climate transition plan is difficult. Company emissions depend on other actors in the value chain, so firms must rely on assumptions to estimate emissions reductions and required funding. Beyond mere compliance with reporting standards, EY analysed the credibility of recent European climate transition plans and their underlying assumptions. We find that most current plans are unrealistic, as they rely heavily on overly optimistic assumptions, provide insufficient information on funding, and lack transparency on the uncertainty of emissions reductions.

More realistic transition plans identify dependencies and use scenario analysis to estimate ranges for emissions reductions and costs, better informing corrective actions in case current measures underperform. As target years approach, this helps companies prevent unforeseen decarbonisation costs and reputational damage from missing targets.

Section 1 of this article presents EY’s observations on recent climate transition plans. Section 2 outlines our recommendations and proposed approach to improving their credibility and resilience.

Section 1

The common approach to date

EY’s observations on current transition plans

Key definitions

- Decarbonisation levers are measures that reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions

- Decarbonisation pathway is the set of levers that a company expects to rely on to achieve its emissions target

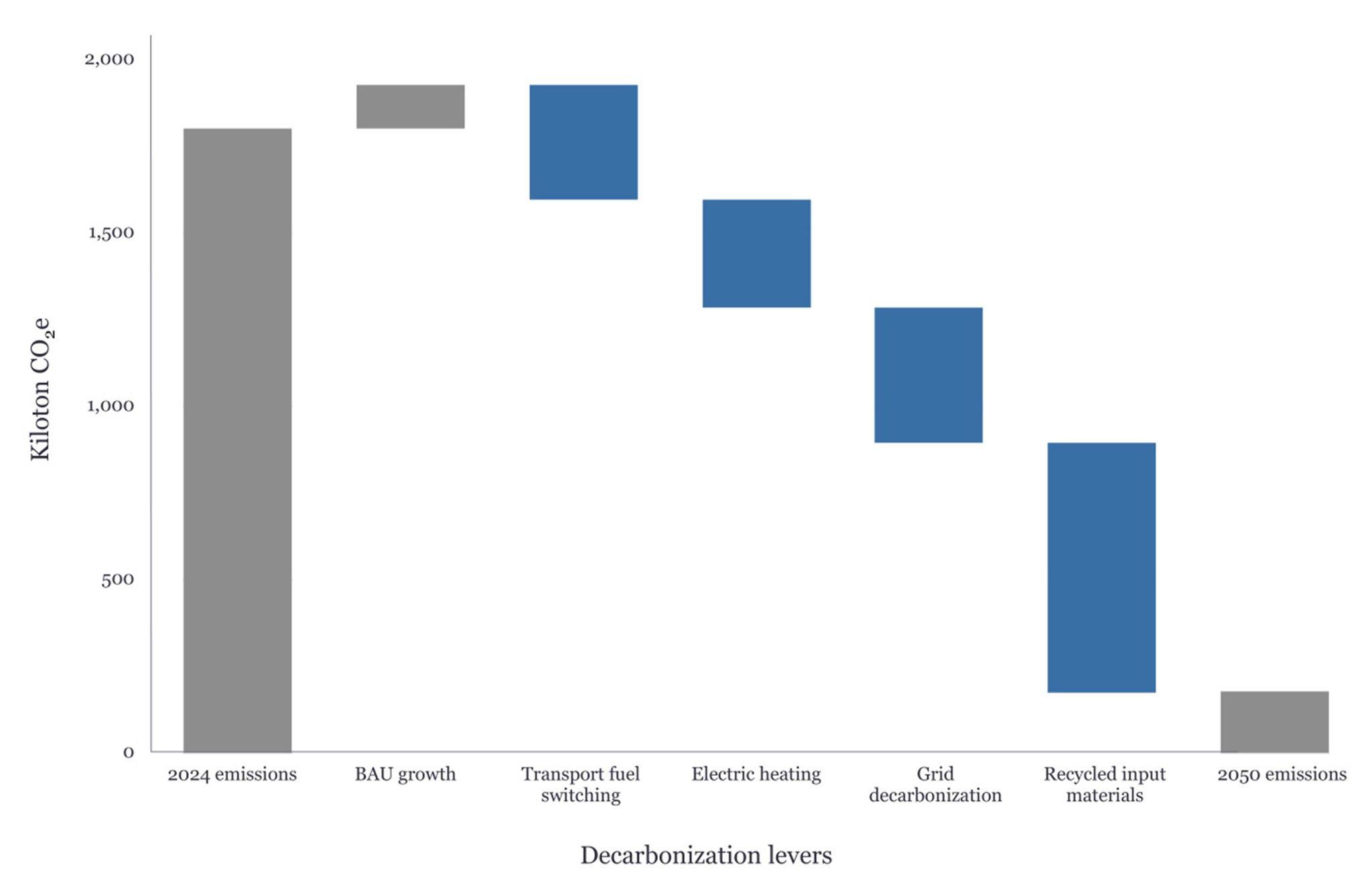

The image below represents a decarbonisation pathway as typically included in a climate transition plan, in the commonly observed shape of a waterfall chart. On the left, the chart starts with current emissions, followed by an increase linked to expected business-as-usual (BAU) growth through 2050. It then shows the effect of decarbonisation levers within the company’s own operations, and additional reductions from changes in its value chain. Finally, the grey bar on the right represents the 2050 Net Zero emissions target.

Typical waterfall chart with decarbonization levers

Observation I: optimistic assumptions behind decarbonisation levers

Estimating the emissions reductions of decarbonisation levers is based on projections, and therefore often depends heavily on assumptions about the development of external factors. Many of these factors are typically also beyond a company’s controli, ii:

- Physical factors include the future availability of clean technologies (such as decarbonized electricity grids or hydrogen networks), resources (non-virgin materials, green steel or low-carbon fertilizers), and skilled labour (workers for low-emissions equipment or electric-vehicle repair);

- Non-physical factors include future market dynamics (green energy prices or cost of capital for decarbonisation funding), regulatory conditions (carbon pricing, subsidies, or permitting processes), and consumer behaviour (willingness to reduce consumption or pay green premiums).

EY finds that the assumptions behind decarbonisation levers are often overly optimistic. This means that, as target years approach, companies may have to make up for lower-than-expected emissions reductions, either by identifying additional levers or by investing more resources to boost existing ones. Current transition plans could thereby expose companies to significant risks of unforeseen decarbonisation costs, reputational damage, and potential legal liabilities from failing to meet emissions targets.

EY analysis finds that companies may end up with up to three times more residual emissions in 2050 than currently predicted.

One example of a decarbonisation lever that often features optimistic assumptions is grid decarbonisation in the value chain (e.g. scope 3 category 3.11). This lever is often modelled using International Energy Agency (IEA) forecasts. Many companies assume electricity grids will decarbonize in line with the IEA’s Announced Pledges Scenario (APS). APS includes recent major national decarbonisation announcements, regardless of whether these announcements have been anchored in legislation.iii Without disputing the need for faster progress toward Net Zero, EY judges the probability of this scenario to be relatively low, as it assumes a grid decarbonisation rate that is well above what current evidence supports.iv A more probable scenario would be the IEA’s Stated Policies Scenario (STEPS), which only considers announcements backed by actual policies and measures (both implemented and under development).v

Replacing one scenario with another can have a big impact on predicted emissions reductions. When replacing the APS scenario with the less optimistic STEPS, EY analysis finds that companies may end up with up to three times more residual emissions in 2050 than currently predicted.vi Such gaps imply significant unforeseen decarbonisation costs, as well as reputational and potential litigation and enforcement risks.vii

Current transition plans could expose companies to significant risks of unforeseen decarbonisation costs, reputational damage, and potential legal liabilities from failing to meet emissions targets.

Observation II: No disclosure of transition plan funding

Our second observation concerns the lack of transparency on capital and operational expenditures necessary for the implementation of decarbonisation levers. While decarbonisation levers can deliver net financial savings, they typically require upfront capital investments in technology and infrastructure, along with ongoing energy and maintenance costs. Many current transition plans do not provide forecasts of such expenditures. Without clarity on the amount, timing and sources of funding for decarbonisation levers, stakeholders cannot assess whether climate transition plans are financially achievable. Without mature financial impact estimates, internal decision-makers and external stakeholders are unable to evaluate whether a climate transition plan can realistically be executed.

Observation III: Emissions reductions of decarb levers are shown as fixed values

Transition plans typically present the estimated emissions reduction from decarbonisation levers as a fixed number in waterfall charts, often without acknowledging the uncertainty behind these numbers. In reality, the emissions reduction potential of levers is uncertain and highly sensitive to factors beyond the company’s control. For each decarbonisation lever, the reported emissions reductions rest on a set of assumptions about how these factors will evolve until the target year. Because reality will inevitably diverge from these assumptions, it is certain that none of the modelled levers will deliver exactly the emission reduction reported. Some may even be far off. Transparency about this uncertainty matters a great deal, to both external and internal stakeholders:

- External readers of transition plans, like investors and government agencies, require clarity on the limitations and underlying assumptions of companies’ projections;

- Internal decision makers must also understand the many uncertainties and assumptions associated with these models, since they form the basis for key investment decisions and other strategic choices.

Visually communicating projected emission reductions as fixed figures in waterfall charts fails to serve the purpose of the relevant stakeholders.

Section 2

A more future-proof approach

EY’s recommendations for more realistic climate transition plans

Responding to the shortcomings in current climate transition plans, EY developed an alternative approach to design more realistic and resilient transition plans. This approach integrates scenario analysis and risk management principles with the suggestions and requirements of leading frameworks such as the Transition Plan Taskforce (TPT) and CSRD.

Core to the approach are the external factors on which decarbonisation levers depend, and the inclusion of different scenarios for each lever. By quantifying the emissions reductions and corresponding financial impacts across multiple scenarios, companies can better identify and manage the risks of decarbonisation levers delivering lower-than-expected emissions reductions.

Below is a visual representation of this approach, in the form of a scenario-based waterfall chart. Each decarbonisation lever is shown with coloured bars representing the emissions reductions under different scenarios. A dotted line traces the scenario that is selected per lever. This line leads to a projected level of residual emissions in the target year, which can be on, above or below the Net Zero target. The light grey shading behind the waterfall shows the range of emissions reductions across the scenarios of all levers. The light red bar on the right shows the significant range in the target gap that the company could end up with by 2050, based on the total range of different scenarios.

Waterfall chart with scenario-based decarbonization levers

The approach offers companies a structured way to develop realistic decarbonisation pathways that remain relevant under changing circumstances.

A. Determining the emissions reduction per scenario begins with identifying the key external factors on which each decarbonisation lever depends — such as the success of national grid decarbonisation strategies, or improvements in fuel efficiencies and end-of-life raw material recovery. These factors are then projected into different plausible futures using location-specific data tied to the company’s assets, suppliers and customers. This increases the likelihood that the scenarios capture local realities rather than generic global averages.ii The emissions reduction and financial impact of each lever are then quantified under each scenario, resulting in a set of decarbonisation levers with different decarbonisation and cost profiles per scenario. This allows the company to select a different scenario per lever, to determine a credible pathway towards the target year.

B. Selecting the preferred scenario per lever is typically based on an assessment of scenario likelihood, the cost per unit of abated emissions, and the company’s risk appetite. For levers over which the company has more control, such as switching to clean fuels in own operations, companies can select more optimistic scenarios, with higher emissions reductions. For levers outside the company’s control, such as grid decarbonisation, we would typically select a more conservative scenario.

By enabling companies to prepare for contingencies, a scenario-based approach lowers the risk of unforeseen costs, reputational damage and compliance breaches.

Our scenario-based approach improves existing transition planning in several ways:

- It helps firms anticipate and manage the risks of underperforming levers. Scenario analysis shows the range of possible outcomes and prepares companies to deploy supplementary decarbonisation measures in time. Where levers are largely within company control, this may mean stepping up investment to maximise their emissions reduction potential. For example, in lever Transport fuel switching, by replacing all vehicles with EVs rather than relying on biofuels. For levers beyond company control, such as Grid decarbonisation, the scenarios highlight the resources required to compensate elsewhere. If electricity grids decarbonise more slowly than expected, the gap in emissions reductions between STEPS and APS scenarios helps companies gauge the extra investment needed in improving product efficiency or securing power-purchase agreements with key customers. By enabling companies to prepare for such contingencies, a scenario-based approach ultimately lowers the risk of unforeseen costs, reputational damage and compliance breaches.

- It keeps emissions and cost estimates accurate by regularly updating scenarios. Transition plans remain relevant only when informed by, and stress-tested against, regularly updated scenarios.viii Having identified the factors that drive decarbonisation lever performance and costs helps companies to periodically update the corresponding assumptions and scenarios. This gives insights to optimise resource allocation to meet targets and to reassess risk-mitigation strategies for underperforming levers.

- It makes the uncertainty around projected emissions reductions more transparent. Quantified ranges for emissions and costs help internal decision-makers factor uncertainty more reliably into strategic choices and budget allocations, while investors and regulators gain clearer insight into the limitations and assumptions underlying decarbonisation projections.

EY supports many organisations in developing climate transition plans. When modelling decarbonisation levers, we adhere to five key principles to ensure their credibility.

- Identify the main external factors on which each decarbonisation lever depends. Then develop geography-specific projections of how these factors may evolve.

- Quantify the impact of each scenario on emissions reductions and on CapEx and OpEx.

- For each lever, select the most suitable scenario for inclusion in the overall decarbonisation pathway, weighing credibility of emissions reductions, financial impacts and risk appetite.

- Define interim targets, to monitor progress and trigger timely mitigating actions.

- Identify mitigation actions in case decarbonisation levers underperform.

If you would like to learn more about how EY can support your organisation in developing a realistic climate transition plan, we invite you to contact Taco Bosman.

Tobias Winter, Laurens Huisman and Jet Rutten, consultants climate change and sustainability services, supported with the article analysis.

Summary

EY analysed recent Climate Transition Plans. We found that current plans are unrealistic due to overly optimistic assumptions and a lack of transparency. This article advocates using scenario analysis to develop ranges for emissions and funding estimates in order to improve credibility.

Related articles

How to build an ESG control framework for risk management and reporting

Discover how an effective ESG control framework contributes to risk management, reliable management reporting, and sustainable value creation for organizations.

How a climate transition plan can strengthen your business model

Climate transition plans are necessary for companies aiming to achieve ambitious climate targets. Read why.

Sustainable AI in Action: How Your Organization Can Reduce Environmental Impact

Read this article for practical guidance on how to embed sustainability across AI development, from data to infrastructure.