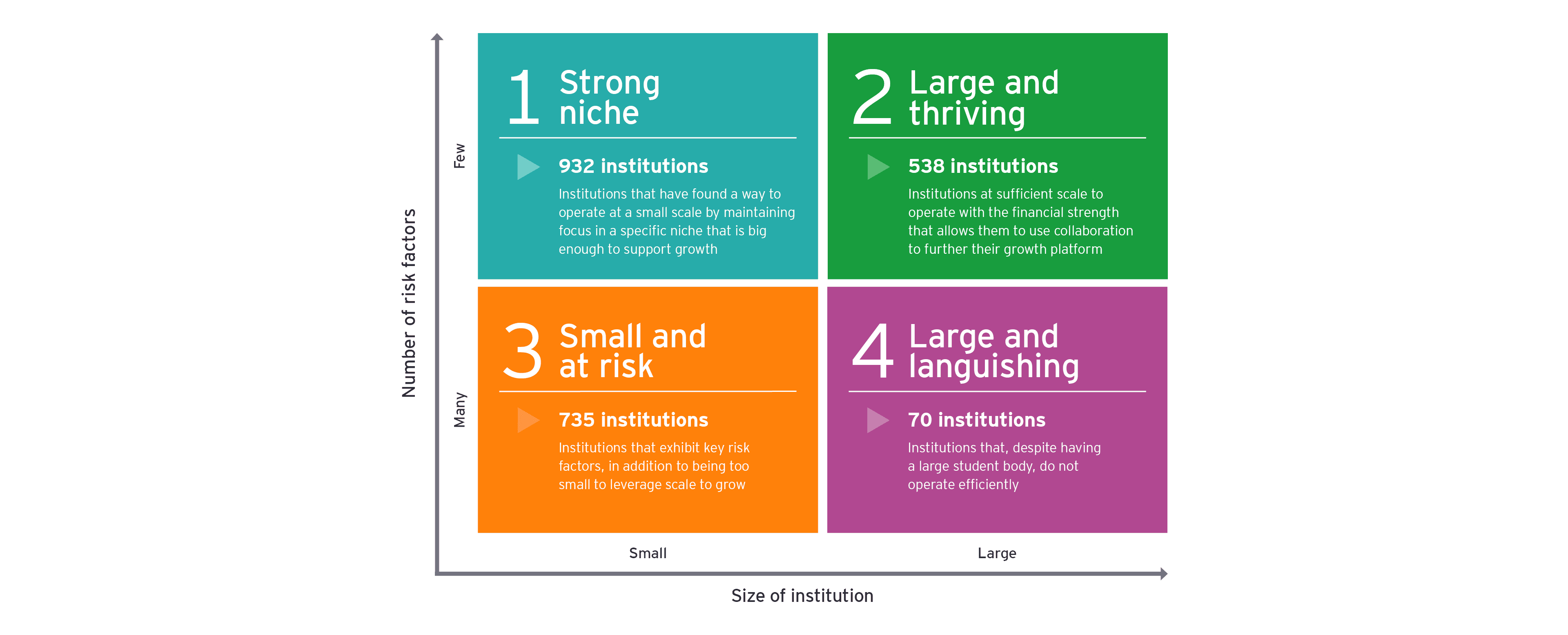

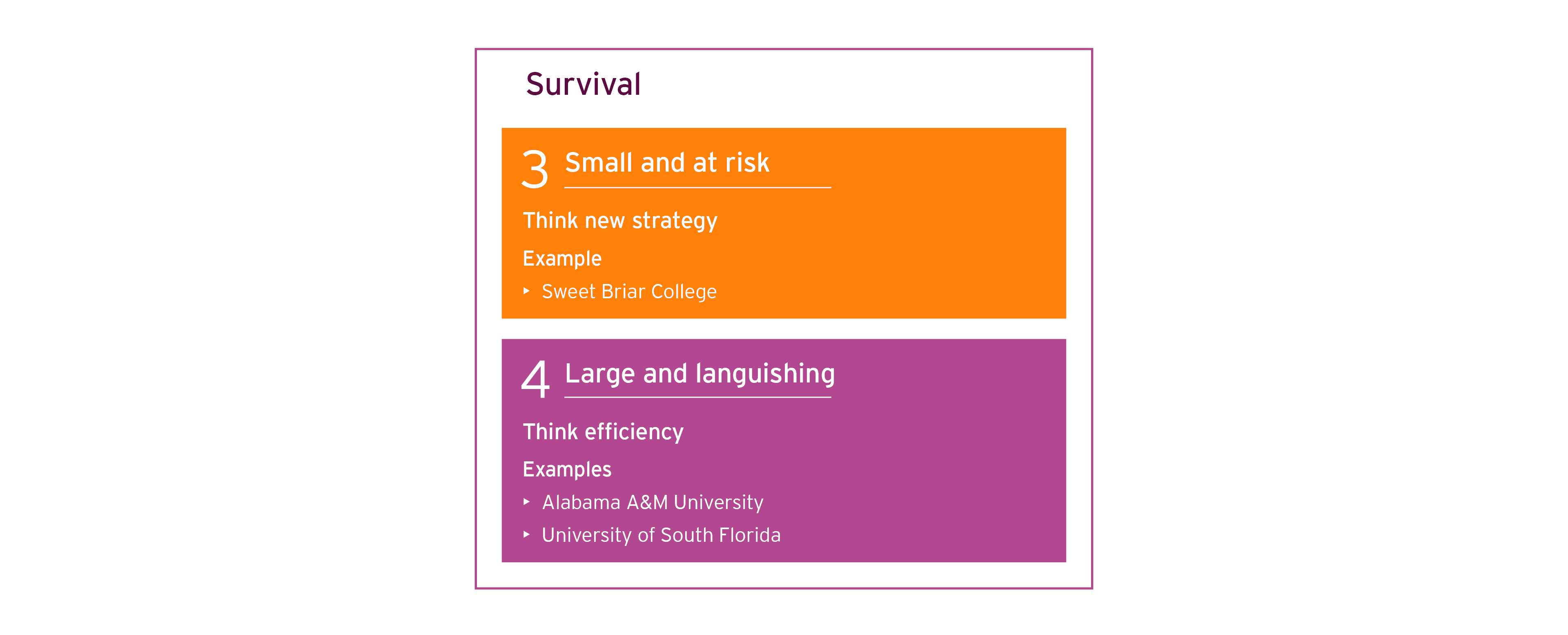

Institutions with many risk factors, Think new strategy, or that are large and inefficient, Think efficiency, need partners to quickly cut their costs. Our analysis found more than 800 institutions in those two categories. They include both small colleges that rely heavily on tuition for the bulk of their revenue and large universities that are running budget deficits.

Finding savings in the proverbial low-hanging fruit through traditional cost cutting in peripheral budget areas is no longer an option for most of these campuses if they have any chance of surviving into the next decade. The small colleges in survival mode are unable to draw additional students even as they come to depend more on them to provide needed revenue.

The large universities in survival mode have consistently raised their tuition rates above the national averages in recent years but still find themselves in a hole financially. The time has come for both sets of institutions to find partners. Neither group can move forward alone.

Proposals to merge public colleges have become more common in recent years but have often run into strong opposition from lawmakers and higher education officials. In Georgia, where universities were suffering from years of budget cuts, higher education leaders attempted to head off controversy by making their consolidation process as transparent as possible and following a set of six principles that guided their work.

The consolidation was also framed as a way to free up funds for student success initiatives, not simply to cut spending. As a result, over the course of three years beginning in 2011, leaders of the University System of Georgia approved six campus mergers.1

Not all institutions that need to pursue a survival strategy are struggling. Sometimes this approach is appropriate for universities that are inefficient as stand-alone entities. In 2013, the Texas A&M Health Science Center merged with the much larger Texas A&M University to better leverage the university’s research prowess.

Before the merger, the Health Science faculty conducted about $80 million in research annually, while the main university had $700 million in research grants. The hope was that if researchers worked more closely together under the umbrella of one university, the institution as a whole could bring in more money overall.2

If survival is your strategy, surprisingly, finding a suitable partner is not the biggest obstacle to collaboration, according to a survey EY-Parthenon conducted of 38 institutional leaders. The toughest barrier to overcome? Pushback from internal stakeholders in the process. So as you begin to lay the groundwork for collaboration, be sure your internal priorities realigned and your various constituencies (trustees, faculty, alumni) understand the need to collaborate before you offer up potential models and partners.

What’s next? The three-step plan: identify, structure and sustain

Step 1: Identify areas for collaboration

Collaboration can take many different forms and doesn’t always need to be seen as resulting in a merger or acquisition. Based on our survey of campus leaders, the most common type of alliance is around academics. Collaboration on administrative and services functions is also common. In both cases, leaders said they chose partners based on complementary strengths. As you begin to identify areas where partnerships might be possible, here are some key questions to consider:

- What type of collaboration is most useful for your institution?

- To what extent is collaboration necessary to stay financially viable? Is there an opportunity to improve value to students or cut costs?

- What administrative, service and academic departments would benefit most from collaboration, and how deep should those collaborations go?

Step 2: Structure potential partnership opportunities

Institutions choose collaborating partners based less on proximity and more on the importance of shared vision. In our survey, college leaders who engaged in academic collaborations said the largest challenge was internal resistance as they attempted to structure the partnership.

When colleges partnered on administrative functions and services, the biggest hurdles were around implementing the agreement, specifically on determining matters of control. As you begin to prepare to structure a deal with a partner, here are some key questions to consider:

- What factors should be used to evaluate the feasibility and attractiveness of a potential partner (e.g., geography, shared vision)?

- Which institution is the best strategic, operational and financial fit for the type of collaboration being sought? What additional collaboration opportunities could we pursue with existing partners?

- How will the collaboration work? Who has to sign off on decisions? How can the two institutions work together operationally?

Step 3: Sustain the benefits of a partnership

Forging a partnership might be the easy task; sustaining the benefits of a partnership over the long term could prove more difficult. In our survey, campus leaders said students were the biggest beneficiaries of partnerships because they improve the value of an education.

While cost savings were less commonly cited as an important concern for academic collaboration, such partnerships are often an opportunity to “save costs” that would otherwise have been required to build out those capabilities. As you search for strategies to sustain the benefits of a partnership, here are some key questions to consider:

- How do we realize the full potential benefits of all cost-cutting opportunities identified in the first two phases (e.g., systems integration, real estate optimization)?

- How do we leverage collaboration to enhance value to students through expansion of services and academic offerings?

Conclusion

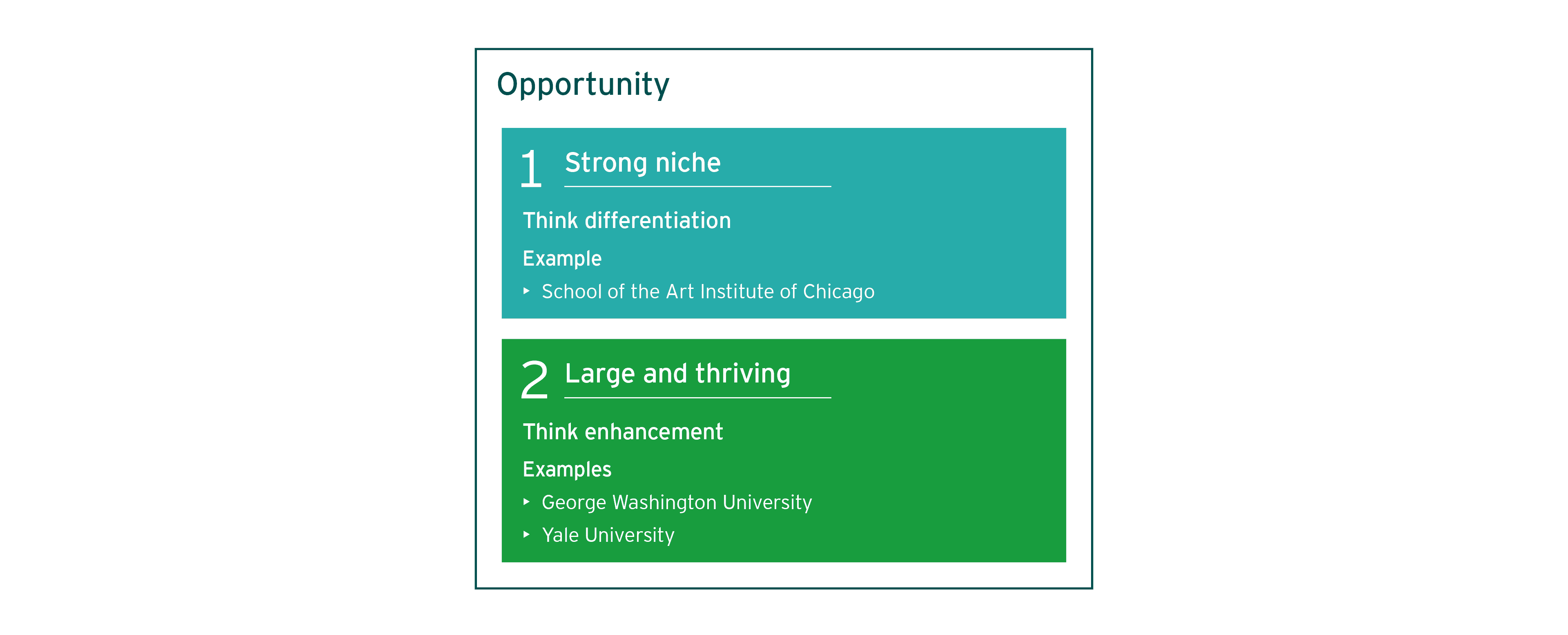

In this new era of higher education, collaboration is a strategy that many institutions will need to follow simply to survive. But partnerships are also a winning approach for colleges operating from a position of relative strength right now.

Collaboration can provide a much-needed boost — and quickly — in academic and co-curricular offerings for institutions without strengths in certain areas. By emphasizing collaboration, we can define this new era of higher education as one of growth through cooperation rather than retrenchment.