EY refers to the global organisation, and may refer to one or more, of the member firms of Ernst & Young Global Limited, each of which is a separate legal entity. Ernst & Young Global Limited, a UK company limited by guarantee, does not provide services to clients.

The CEO of a major Australian industrial company recently quipped to one of my EY colleagues: “Soon we’ll all be on our knees asking for help in Canberra.”

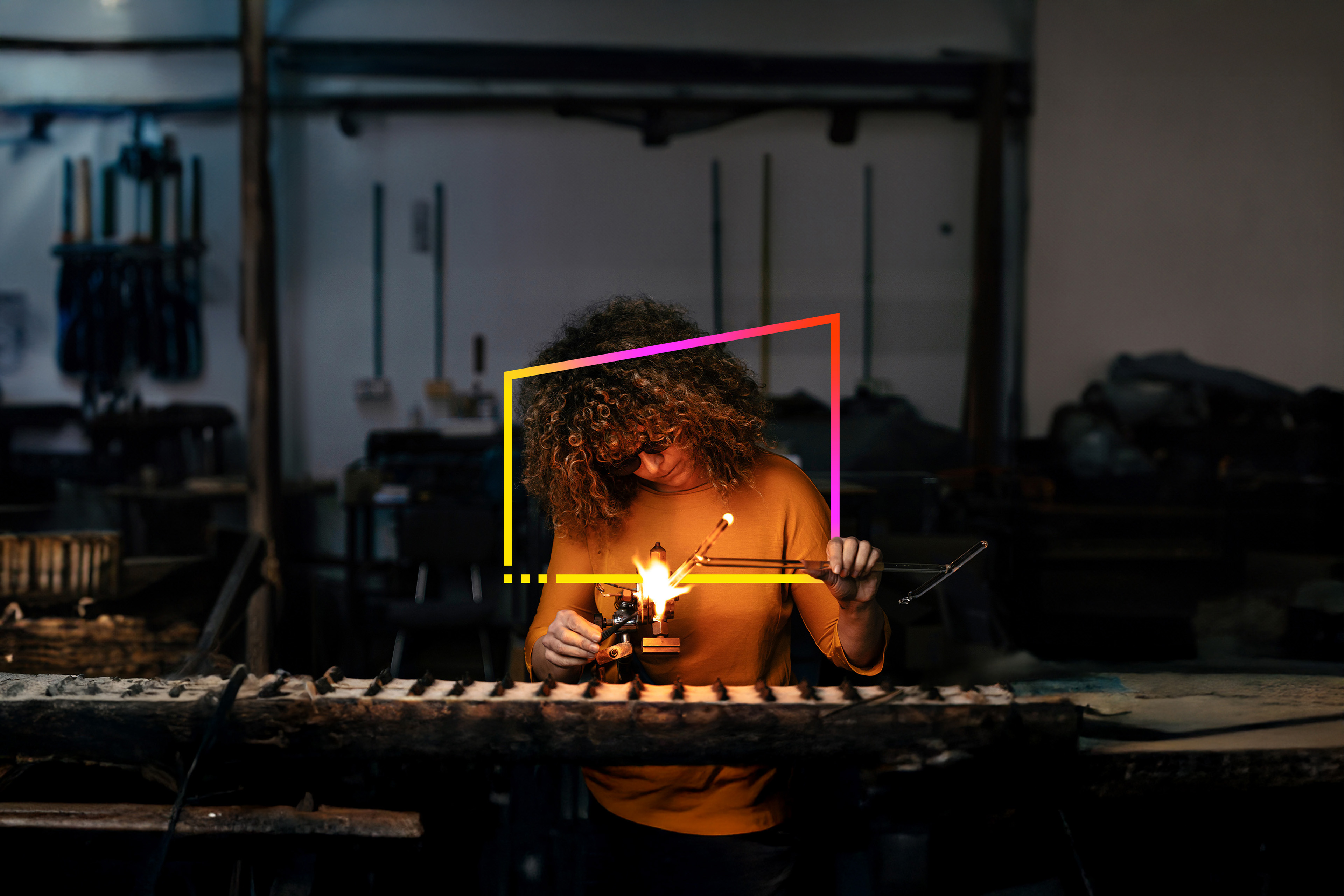

The “we” is Australia’s heavy industries, the companies with sprawling plants around Australia’s ports and urban fringes. They employ people like my boilermaker brother and my dad, who spent decades as a fitter before retiring. These firms are the backbone of the economy, producing the concrete and steel that hold up our bridges, the aluminium that frames our windows, the fuel that powers our cars, and the fertiliser that feeds our crops.

Could we survive without them? Technically, yes. Imports could fill the gap - and increasingly, they have. Imports of steel rose from 1.4 million tonnes in 2000 to 6.6 million tonnes in 2024, while our domestic production fell from 8.9 million tonnes to 5.3 million tonnes. Our automotive fuel imports have increased from 10 billion litres to 41 billion litres while our production has halved. Our imports of fertilisers are nearly three times higher than in 2000, while our domestic production is virtually unchanged.

But a future without heavy industry is uncomfortable for many, especially its workers. It’s also awkward for the Government, which has staked billions on its Future Made in Australia policy. And it’s risky in a world where geopolitical tensions or pandemics could choke supply chains threatening our ability to look after ourselves in times of conflict or shortage.

BlueScope CEO Mark Vassella noted at the National Press Club last year: “As COVID showed us, there are some industries where we need to maintain a sovereign capability. Put another way, there are some industries where their value is far greater than just toutput.”

So why are these once-profitable giants struggling? The economy isn’t in recession. Demand hasn’t collapsed.

Start with costs. The producer price index for manufacturing industries has increased 35 per cent from early 2020 to now. For construction, it has been similar at 36 per cent. That compares to a 23 per cent increase in the consumer price index over the same period, which has led households to bemoan the cost of living.

Energy, labour, maintenance and capital costs have all risen sharply for Australian businesses. Gas is a case in point. In 2024-25, Australian industry paid an average wholesale price of $12.90/GJ for gas on the east-coast, more than double what it was just four years ago. That is despite booming Australian gas production over the last decade.

New costs due to everything from construction codes to industrial relations laws to energy transition challenges add further expenses. Although policies in these areas are often well intentioned, cost escalation hurts Australian firms that are price takers in global markets. They cannot use the price lever to recover higher energy and labour costs, particularly when wages and on-costs rise faster than productivity.

Trade barriers haven’t helped. From Trump-era tariffs to a tangle of sanctions, export controls and compliance rules, other nations are shielding their own industries and squeezing ours out. For some Australian firms, losing overseas sales makes domestic supply less viable.

If our heavy industries retire output, we lose them forever. There’s no quick way to switch the lights back on in times of emergency or renewed need. And we don’t just lose plants and equipment; we lose the engineers, physicists, scientists, and the skilled tradespeople who design, build, operate and maintain complex systems. Without an industrial base, we risk producing more professionals for a services economy while ending up with fewer STEM and trade skills.

International conditions are largely beyond our control. But domestic policy settings aren’t and that’s where the real debate lies. Governments can help, but the motivation matters. Policies should be aimed at removing structural problems and promoting long-term growth opportunities that build on our natural advantages; not scoring political points.

Take the east-coast Domestic Gas Reservation Scheme introduced in December. It’s reasonable policy and levels the playing field for domestic gas users. From 2027, LNG exporters must reserve 15-25 per cent of production for local use. That somewhat corrects a market distortion that left domestic businesses paying global prices.

Contrast that with recent government subsidies to three steelworks and smelters which have totalled over $2.6 billion. This support has solved some micro problems, helped workers and communities through difficult times, and in some cases allowed a shift to cleaner production. But governments must ask: are subsidies the best use of borrowed taxpayer dollars? Does it create moral hazard, signalling bailouts for any struggling operator with a community footprint? And could those billions instead be used to cut taxes or duties for thousands of firms that might help deliver efficiencies and therefore higher wages in cleaner, future-facing jobs?

Heavy industry should only receive support that boosts productivity, not props that perpetuate inefficiency. Federal and state governments can help them reduce costs, innovate, and compete. This means meaningful tax reform, investment incentives, digital transformation, and sustainability incentives.

As EY argued in our submission to the Productivity Commissions’ five pillars inquiries, reviewing our tax system is critical. The current 30 per cent corporate tax rate is well above the OECD average of 21 per cent and R&D tax incentives are out of date and not incentivising investment as they could be. To compete, Australia needs permanent incentives that send a clear signal to local and global investors that we stand for growth built on economic strength and political stability and maturity.

Australia’s businesses and policy makers faces a choice: de-industrialise and rely on imports to build the economy around us or collaborate to determine the policies and partnerships that will secure competitiveness amongst Australia’s remaining heavy industries. The choice will shape not just our factories, jobs and landscapes, but also our future prosperity.