Paving the way: Opportunities and obstacles

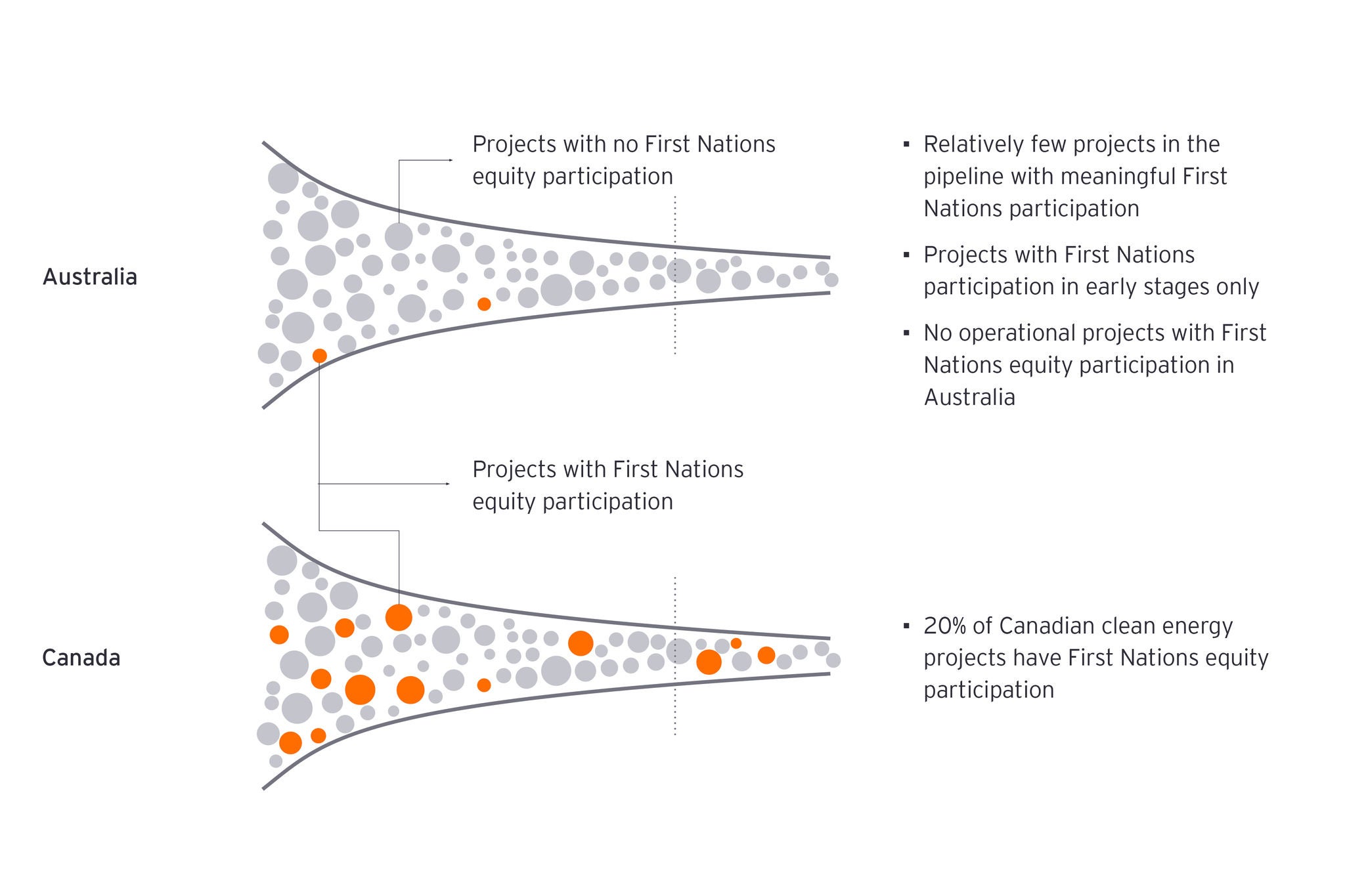

Australia is well-placed to adapt the lessons from Canada. Recent initiatives like the First Nations Guidelines for the NSW Electricity Infrastructure Roadmap, and the Australian government’s Capacity Investment Scheme (CIS) are beginning to define clearer pathways for participation.

For example, the CIS includes eligibility criteria requiring the protection of First Nations cultural heritage and the environment, as well as merit criteria that demonstrate ongoing engagement and benefit sharing.

However, several persistent barriers stand in our way:

- Low awareness: Limited understanding of the financial benefits of First Nations participation leads investors to focus only on minimum legal requirements.

- Uncertain valuation: Few precedent projects make it difficult to assess the true value of participation for both investors and First Nations groups.

- Perceived high transaction cost: Early movers may incur higher costs to establish and refine workable legal and commercial models, contributing to a perception that participation is expensive.

- Perceived additional risk: Investors associate participation with added governance layers, increasing perceived project risk.

- Capacity and capability gaps: Many First Nations groups have not yet developed the capability and resources to engage effectively, while some developers lack the experience or skills to build robust partnerships.

- Legacy of mistrust: Australia’s colonial history of inadequate consultation and adversarial relationships has led many First Nations groups to approach projects with concerns about fairness and informed consent.

First mover opportunities

Early movers can set the standard. The Yindjibarndi Renewable Energy Project in Western Australia demonstrates the potential. The project is jointly owned by ACEN Renewables (75%) and the Yindjibarndi Aboriginal Corporation (25%), with Stage 1 comprising 400MW of solar generation, options for battery storage and 300MW of wind generation capacity. The initial stage alone represents an investment of more than AU$1 billion.

Embedded within the project’s commercial framework are clear commitments to First Nations participation: Yindjibarndi approval is required for all proposed project sites; the Corporation must hold equity of 25% to 50% in all projects; Yindjibarndi-owned businesses receive preferred contracting opportunities; and there are dedicated training and employment pathways for Yindjibarndi people.

Our interviews with both project owners revealed a range of investor benefits already being realised. ACEN Renewables highlighted speed to market, improved offtake terms, faster land access that reduces project delays and risks, and a reputational uplift that enhances brand value and increases secondary market appeal.

The Yindjibarndi Aboriginal Corporation emphasised that Indigenous Land Use Agreements and environmental approvals were completed significantly faster than comparable projects, enabled by the strong equity partnership and broad First Nations support. In addition, the project has unlocked strong relationships with a local workforce.

Time to act

Australia’s clean energy transition is a complex undertaking – technically, financially and socially – but it also presents an opportunity for investors and policymakers to redefine success. We can build a system that delivers affordable, reliable, clean energy while recognising the rights, interests and potential of First Nations peoples.