Chapter 1

Capital allocation is an ongoing, integrated, and iterative process.

Broadening the opportunities to create value across a time frame and an ecosystem of possible partners.

When surveyed prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, 72% of EY’s clients admitted that their capital allocation processes needed improvement, 42% of CFOs cited insufficient data as one of the primary barriers to the optimal allocation of capital, and as many as 63% confirmed that they had repurchased shares primarily to fulfil shareholder or analyst expectations.

While some market commentators tend to think of capital allocation purely in terms organic investments, i.e., capex, EY’s viewpoint is that capital allocation, as a key driver of value creation, has to be integrated with overall corporate strategy, and has to include all uses of capital, including investments, returning capital to shareholders and even divestitures. Decisions on the best use of capital evaluate and trade off:

- debt repayment;

- dividends;

- capex;

- share repurchases;

- inorganic growth through acquisitions;

- investments in research and development; and

- (even) sales and marketing.

An effective allocation must be aimed at enabling value creation by finding and funding the right mix of investments, given a company’s financial and operational constraints.

This process also has to have impact across multiple dimensions, including time horizons and different organisation levels. So, for example, long-term capital planning has to address the long-term strategic objectives of an organisation – 3 to 5 years out – while short term capital budgeting must speak to a near-term horizon of 1 – 3 years, with both a top-down and a bottom-up dimension. And, the more complex an organisation, the more it has to factor in various levels at which capital allocation is done:

- at an enterprise level, the board and senior management have to decide between returning capital to shareholders through dividends and share buybacks, paying down debt and organic and inorganic investments;

- from a segmental perspective, management may have to decide how to differentially invest across business units and how much capital to allocate to various investment categories; and

- within businesses or functional units, management may be deciding which discrete investments to accept, prioritise and approve.

EY’s model for capital allocation urges our clients to adopt a 4-step iterative and ongoing process – not only to allocate capital in the first instance, but to ensure ongoing monitoring, adjustment and review to ensure that each cent of capital mobilised to achieve a specific objective, contributes to the creation of long-term value for all stakeholders.

- Selecting appropriate key performance indicators (KPIs): The process of deciding how best to allocate capital has to start with the objectives that a company has set for itself, and these objectives have to balance both financial and broader considerations. In Part 2 of this series, we will be exploring a balanced approached to setting KPIs that enable a company to deliver appropriate financial returns to shareholders, while also achieving other objectives such as maintaining a social license to operate or transitioning to net zero carbon.

- Creating and developing business cases for different uses of capital: Too often companies fail to identify suitable uses of capital, use inappropriate data to create and support the business case for an investment, or fail to identify and consider all of the risks associated with a project.

- Accepting, prioritising and approving the allocation of capital: While most companies have governance structures in place to approve the deployment of at least some forms of capital, EY’s experience suggests that corporate dynamics, a lack of data and other process shortcomings often undermine the right outcomes.

- Execution monitoring: Especially in the field of large capital projects, a lack of monitoring and assessment at each stage of execution, can result in wasted expenditure, and a failure to put a hold on projects that are no longer able to deliver the returns on which initial approval was premised.

Chapter 2

Strategy and capital allocation

The key performance indicators associated with strategy must drive capital allocation.

In Africa and South Africa, the strategic dialogue in companies has evolved to recognise that the role of a business has become far greater than just generating returns for shareholders. It is also an employer, a generator of revenue for its host government(s), a contributor to the communities in which it operates and a force with environmental and social impacts. Against this backdrop, companies have come forward stating ambitious targets addressing elements such a commitment to net zero carbon and greater emphasis on net zero carbon.

When surveyed for EY’s CEO Outlook 2022, 24% of respondents viewed a return on invested capital (ROIC) as an “extremely important” driver of value, while 38% had the same view on environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors. 47% of CEOs were of the view that they investors were “extremely supportive” of well-articulated investments – suggesting to us that CEOs are now compelled to constantly update their narrative to be credible with their broader stakeholder community, and to be ready to respond to any concerns quickly.

All of the above suggests that an old-fashioned approach in which an investment committee approves a project based on simple financial measures, is outdated.

Our view is, instead, that the attributes to consider in the selection of key performance indicators (KPIs) for a capital allocation framework should be:

- linked to overall company and business unit strategy – a critical starting point is an organisation is to deploy its resources to achieve its objectives;

- consistent with personnel review metrics and goals – there is little sense in de-linking the KPIs set for staff, from those of the broader organisation;

- qualitative as well as quantitative – especially in the context of an increased emphasis on ESG and the long-term benefits that brings to an organisation;

- operational as well as financial;

- reflective of the attributes of the investment being considered – some projects could, for example, contribute more towards achieving financial objectives, while other may promote other corporate objectives;

- industry-specific, if necessary;

- focused on value creation;

- cognisant of risk and return – too often risks associated with projects are not adequately captured or considered;

- consistent across investment categories to allow for comparison and ranking – which is only possible with the use of a balanced scorecard that enables decision-makers to offset the relative important of achieving various KPIs; and

- able to efficiency track and report selected metrics.

Optimal allocation of capital

42%CFOs cited insufficient data as one of the primary barriers to the optimal allocation of capital.

For this reason, the second step in the capital allocation is data critical and requires that a company develop and provide clear guidance on how investment cases should be built and articulated to ensure that each potential use of capital, placed before its relevant decision-making body:

- is defined and developed using consistent methodologies, analyses and consider the impact of scenarios that might be top-of-mind for decision-makers – items as simple as criteria for the development of financial models, consistent and relevant macro-economic inputs and standard checklists for risks and other investment factors can make a significant impact;

- provides a consistent set of criteria, considerations and outputs for decision makers to consider while weighing investment alternatives – all too often the corporate memory of individual decision-makers outweigh objective data;

- appropriately considers both risk and return so that outputs are focused on value creation over the life of the investment (see Part 2 of this series);

- gets the organization thinking and speaking about investments in a consistent manner, while establishing a common view on cost and value drivers;

- provides a balanced-scorecard view for understanding both the quantitative and qualitative elements that might impact the organization, including articulation of any potential risks; and

- is developed with input from relevant stakeholders across the organization (i.e., financial, operational and technical teams) to provide for a more comprehensive and thoughtful analysis.

Successful organizations acknowledge that “one size does not fit all.” As outlined in Part 1, it is critical that these processes are fit for purpose for the business unites, business segments and the overall organization into which they fit.

EY often sees examples of companies trying to take investment decisions but wrestling with challenges resulting from this important second step in the capital allocation process not being taken:

- The way in which projects are presented may different across an organisations – often because policies and guidelines are not formalised – resulting in management acknowledging that they are trying to compares apples to pears in choosing between two uses of capital – but not knowing how to adjust to make the two uses more comparable.

- The information provided to decision-makers is not sufficiently complete to really enable them to make a decision – and often it is the omission of important information that means that they are not able to sufficient consider or measure risks against returns – as if the omission of risks could improve the prospects of an investment.

- The organisation uses one set of metrics – often financial – to measure all investments – thereby not allowing other important strategic objectives to be considered.

Good investment cases are based on sound financial information, scenario and sensitivity analyses and other elements of a strong investment framework.

Part 4 of this series focuses on the next steps, which we have already alluded to extensively in this piece: once the investment case is created and developed, it has to be approved within a sound framework that does not simply approve an investment – but also ranks and prioritises it.

Chapter 3

The investment case

What capital allocation decisions are based on.

Part 2 of this series made it easy to be carried away by the aspirational setting created by taking a corporate strategy and translating it into key performance indicators to be used to allocate capital. And while that first step does indeed have the power to inspire, it is in the investment committee and board meetings, where investment cases are presented for approval, that the rubber hits the road. As stated in Part 1, however, 42% of CFOs cited insufficient data as one of the primary barriers to the optimal allocation of capital.

EY therefore advocates a structured approach to the creation and development of each use of capital, in the form of an investment case, which provides a consistent and objective basis for each potential investment (and here we include dividends, share buybacks, repayment of debt, etc) to be developed, compared, approved and, ultimately, monitored. Without a structured approach to investment cases, the approval process can be (or seem) subjective and influenced by politics or “pet projects” rather than objective measures.

For this reason, the second step in the capital allocation is data critical and requires that a company develop and provide clear guidance on how investment cases should be built and articulated to ensure that each potential use of capital, placed before its relevant decision-making body:

- is defined and developed using consistent methodologies, analyses and consider the impact of scenarios that might be top-of-mind for decision-makers – items as simple as criteria for the development of financial models, consistent and relevant macro-economic inputs and standard checklists for risks and other investment factors can make a significant impact;

- provides a consistent set of criteria, considerations and outputs for decision makers to consider while weighing investment alternatives – all too often the corporate memory of individual decision-makers outweigh objective data;

- appropriately considers both risk and return so that outputs are focused on value creation over the life of the investment (see Part 2 of this series);

- gets the organisation thinking and speaking about investments in a consistent manner, while establishing a common view on cost and value drivers;

- provides a balanced-scorecard view for understanding both the quantitative and qualitative elements that might impact the organisation, including articulation of any potential risks; and

- is developed with input from relevant stakeholders across the organisation (i.e., financial, operational and technical teams) to provide for a more comprehensive and thoughtful analysis.

Successful organisations acknowledge that “one size does not fit all.” As outlined in Part 1, it is critical that these processes are fit for purpose for the business unites, business segments and the overall organisation into which they fit.

EY often sees examples of companies trying to take investment decisions but wrestling with challenges resulting from this important second step in the capital allocation process not being taken:

- The way in which projects are presented may different across an organisations – often because policies and guidelines are not formalised – resulting in management acknowledging that they are trying to compares apples to pears in choosing between two uses of capital – but not knowing how to adjust to make the two uses more comparable.

- The information provided to decision-makers is not sufficiently complete to really enable them to make a decision – and often it is the omission of important information that means that they are not able to sufficient consider or measure risks against returns – as if the omission of risks could improve the prospects of an investment.

- The organisation uses one set of metrics – often financial – to measure all investments – thereby not allowing other important strategic objectives to be considered.

Good investment cases are based on sound financial information, scenario and sensitivity analyses and other elements of a strong investment framework.

Part 4 of this series focuses on the next steps, which we have already alluded to extensively in this piece: once the investment case is created and developed, it has to be approved within a sound framework that does not simply approve an investment – but also ranks and prioritises it.

Chapter 4

Ranking and prioritising allocated capital

Incorporating value levers makes project sustainability more transparent.

The hard work is not done once a specific use of capital has been identified, and the solid work to prove the case for that use of capital is completed. Just as successful organisations must effectively compete for capital in the market, so projects and investments will have to compete inside a single organisation for capital. Even projects that enable a company to meet some or all of its key performance indicators (KPIs), using a balanced scorecard – as outlined in Part 1 – must be accepted, ranked and prioritised.

It is easy – and potentially flawed – to confuse the processes of accepting, raking, prioritising and re-assessing projects in a large organisation with multiple calls on capital:

- Accepting an investment case is a critical first step, in which a specific use of capital is evaluated on its own merits to determine if it meets muster on metrics and is aligned to strategy – i.e. it will support a company achieving its KPIs. This step, however, only results in a potential investment being admitted into the queue.

- The next following step – which can vary in complexity based on the size of the organisation and the competition for capital within it – is to force decision-makers to rank the competing investments and to allocate capital to them, based on overall corporate priorities. This step is one that could carry additional material risk – allocating capital too late, or not allocating enough capital.

- The third and final step – and an often overlooked one – is to constantly re-evaluate the company’s queue of accepted investment cases, to weigh them against the financial plan, and specifically to re-assess previously approved projects in the current capital environment.

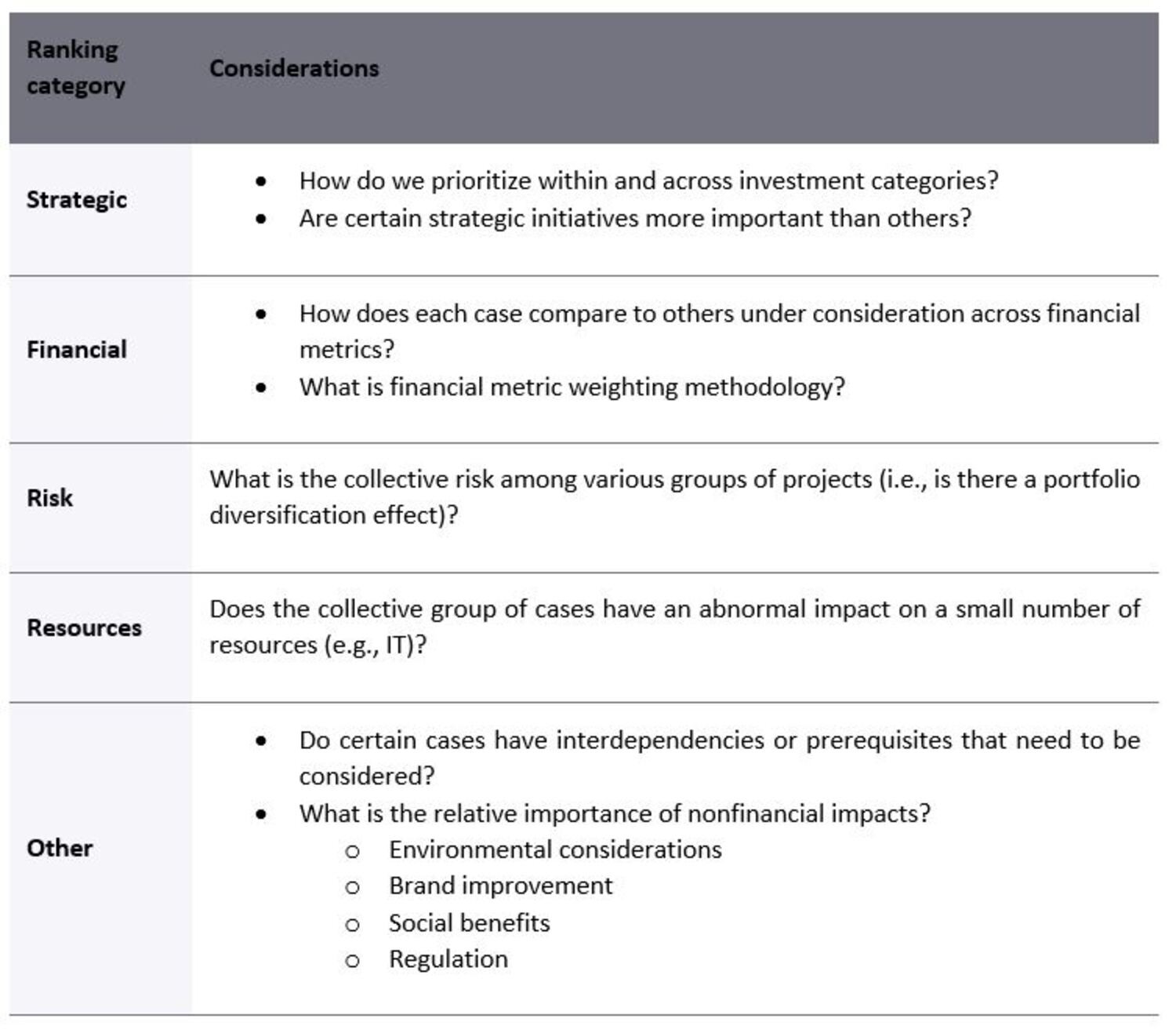

While it is possible to expand exhaustively on each one of the above, it is the process of ranking and prioritising investment cases – deciding what use of capital is more important than another at a point in time, that deserves more focus in this piece. The matrix set out, below, illustrates how an investment committee or a board may look at a portfolio of accepted potential investments, and then rank them:

This prioritisation process will vary across industry and sector, and not all organisations will require – or even tolerate – the same level of formalisation and rigour in the capital allocation process. If an organisation has sufficient capital at its disposal, it may not even be necessary to limit the capital allocation, as all desired uses could be funded.

A transparent and consistent approach to evaluation and approval can, however, enable companies to identify and appropriately calibrate any subjectivity in the decision-making process, and include all relevant stakeholders across an organisation to evaluate and constructively challenge presented options, including costs, benefits and data quality.

In our final instalment in this series, we will explore the monitoring process, which seeks to explode the sunk-cost myth, and encourage companies to look project overruns and delays squarely in the eye.

Chapter 5

The investment case

What capital allocation decisions are based on.

This final step in the process has two elements to it:

- Execution monitoring, which represents the process of evaluating the costs, benefits, and other factors relative to assumptions in the approved business case while an investment is in flight, and provides an opportunity for the real-time identification of risks or variances from project plans and allows for timely course correction; and

- Post-mortems, which represent the process of evaluating the costs, benefits, timeline, and other factors relative to assumptions in the approved business case when an investment has concluded, and provides an opportunity to learn from past investment successes and failures and improve the decision-making process for future investments.

Both are equally hard to consider, because overruns and delays inevitably represent some form of planning, system, control or governance failure within an organisation. It is therefore not surprising that our clients face a number of challenges across governance, processes and reporting.

- At a governance level, projects most typically fall prey to a lack of clarity on accountabilities, resulting in a lack of consequences when internal processes are breach – which can be exacerbated when there is limited stakeholder engagement and communication on project performance.

- On the process front, difficulties often arise either as a result of processes that don’t allow an organisation to differentiate between baseline performance, and the incremental performance contributed by the investment, or processes that don’t allow an organisation to assess how changes from the original plans (typically cost and time overruns) can impact the contribution that an investment was supposed to make to the achievement of its range of KPIs.

- Finally, reporting can contribute to an organisation’s inability to monitor an investment: this is especially problematic where critical project status information is either not collected or communicated, project reporting focuses only on selected KPIs, instead of the full range on which it was approved, or inconsistent reporting metrics are used.

Markets are often shocked by unanticipated project overruns and delays, and the knock-on effects not only damage the confidence of investors, but also creates fear and uncertainty on the part of lenders, employees and other stakeholders. For this reason, the rigour in accepting and approving projects, have to be matched by rigour in measuring project performance on an ongoing basis, and communicating that performance to relevant stakeholders.

A management team that can evidence a strong record of performance in allocating and managing capital to create long-term value for stakeholders, is respected in every market, and rewarded with more capital to invest. In EYs view, this kind of performance requires strong systems and processes, implemented with discipline, rigour and insights.

Summary

From strategy through to execution organisations require an interconnected approach to understanding long-term value to enabling objective, agile, not only project-level but sustainable capital allocation.