EY refers to the global organization, and may refer to one or more, of the member firms of Ernst & Young Global Limited, each of which is a separate legal entity. Ernst & Young Global Limited, a UK company limited by guarantee, does not provide services to clients.

Health systems face rising strain. Discover why shared responsibility and community partnership are vital for sustainable care

In brief

- Health systems are at a turning point, with a growing gap between what people expect and what traditional models of care can sustainably deliver.

- Prevention and partnership are essential to building sustainable, person-centred care that reflects real lives and community strengths.

- Shifting to a “doing with” approach requires a fundamental shift in culture, power and how health systems work with people.

Health systems around the world are facing a turning point. For decades, many were built on a post-war social contract that promised cradle-to-grave care, delivered largely through state-backed provision. This settlement was rooted in a powerful sense of collective responsibility: governments would provide, and citizens would receive. But today, this model is under growing strain. Rising demand, ageing populations, chronic illness, widening inequalities, workforce pressures, and mounting financial deficits have created a widening gap between what people expect and what health systems can realistically deliver.

The result is a deepening crisis of confidence and sustainability. In many settings, healthcare budgets are stretched to their limits or significantly overspent. Wellbeing levels remain stagnant or are in decline, while public dissatisfaction grows. Even where policy has promised greater choice, access, or personalisation, systems are struggling to keep pace. The challenge is not simply one of efficiency or more funding; it reflects a deeper misalignment between societal expectations and the foundational design of the system itself.

A key driver of this misalignment lies in the way the public has historically been positioned in relation to the healthcare system. Traditionally, individuals were treated as subjects - passive recipients of expert-led care, with limited agency or involvement. Over time, this shifted to a model in which people were seen as consumers, entitled to a menu of services delivered for them, underpinned by the language of rights, choice, and satisfaction.

However, both models have shown their limitations. The subject role denies people’s capacity to influence, shape, and sustain their own health and the health of their communities. The consumer model, while intended to empower, often generates rising demand, transactional expectations, and entitlement that overburden systems already stretched thin. Neither subjecthood nor consumerism is truly sustainable in the face of modern pressures.

This has led to a growing recognition that the public must instead be seen - and engaged - as partners: capable, active contributors with the insight, motivation, and agency to help shape, co-produce, and sustain health and wellbeing; partners who are active and engaged in the development of healthy places, not merely consumers of sick-care services.

This reframing forms the basis of an asset-based partnership approach. Rather than focusing solely on deficits (illness, needs, service gaps), this approach recognises people’s strengths, lived experience, informal networks, communities, and local capacity – including Community and Voluntary Sector Organisations - as essential components of a healthier society. By establishing a shared responsibility for health, it has the potential to open up essential conversations about prevention, the protection of individuals’ own health and the role of communities and neighbourhoods as key to health service sustainability in the decades ahead.1

In theory, this shift from “doing to/for” to a “doing with” approach should not be difficult. Afterall, on the face of it, most people agree – at least in principle – that collaboration and partnership with the public is the right way forward. Attend almost any healthcare conference today, and you’ll find co-production and patient partnership high on the agenda. So, if we all agree this is the right direction, why aren’t we doing it? Because moving from belief to behaviour is the hardest part.

It requires a cultural transformation. Healthcare systems have long been built around professional authority and institutional delivery. Healthcare systems tend to talk to people about the service delivery issues that are important to the system, rather than the issues that are important to the people.2 To deliver on a “doing with” approach, systems must reorganise around the needs and strengths of people and communities, not merely the operational logic of institutions or professional silos. This requires the development of services within place-based and person-centred structures, aligning care around real lives rather than rigid organisational boundaries.

Change must happen at many levels and it requires collaboration across sectors that traditionally work in silos. Policy, funding, organisational structures, workforce behaviour, public mindset, and community capacity all need to shift - connecting healthcare with housing, education, employment, justice and civil society. This demands new partnerships, governance, and coordination and progress is only as strong as the weakest link.

Power must be genuinely shared. Moving from “doing to/for” to “doing with” requires redistribution of control, which can feel uncomfortable for professionals and institutions used to holding decision-making authority. They may worry they will still carry the ultimate accountability if decisions made collaboratively lead to poor outcomes. When things go wrong, blame typically flows upwards to professionals and institutions - not to systems of shared responsibility.

Systems are structured for activity, not agency. Existing funding, performance metrics, and regulatory frameworks prioritise service outputs over citizen engagement, partnership, or community assets.

It challenges linear, centralised delivery models. Truly asset-based, partnership approaches require moving beyond collaborative design to collaborative delivery - where individuals, families, communities, and civil society organisations play an active role in promoting and maintaining health, not just responding to illness. These approaches are inherently relational, diverse, and local - making them harder to scale, standardise, and measure.

Public trust in systems is fragile. In a “doing with” approach, accountability becomes reciprocal: the system must be open, inclusive, and responsible, while citizens are active participants in shaping and sustaining the health of their communities. However, asking people and communities to step in when they feel underserved or unheard can feel like shifting responsibility. Without careful framing, people may interpret shared responsibility as the system stepping back or offloading burdens onto individuals and communities.

The public – and those tasked with delivering services to them - are not always ready or supported to take on new roles. Agency depends on confidence, capability, health literacy, and community infrastructure - which are not evenly distributed. If we are not careful, a “doing with” approach can result in voices which are already heard becoming louder; communities which are already organised getting more influence; and those who face the greatest barriers being left even further behind.

Despite these challenges, there are examples of where systems are changing;

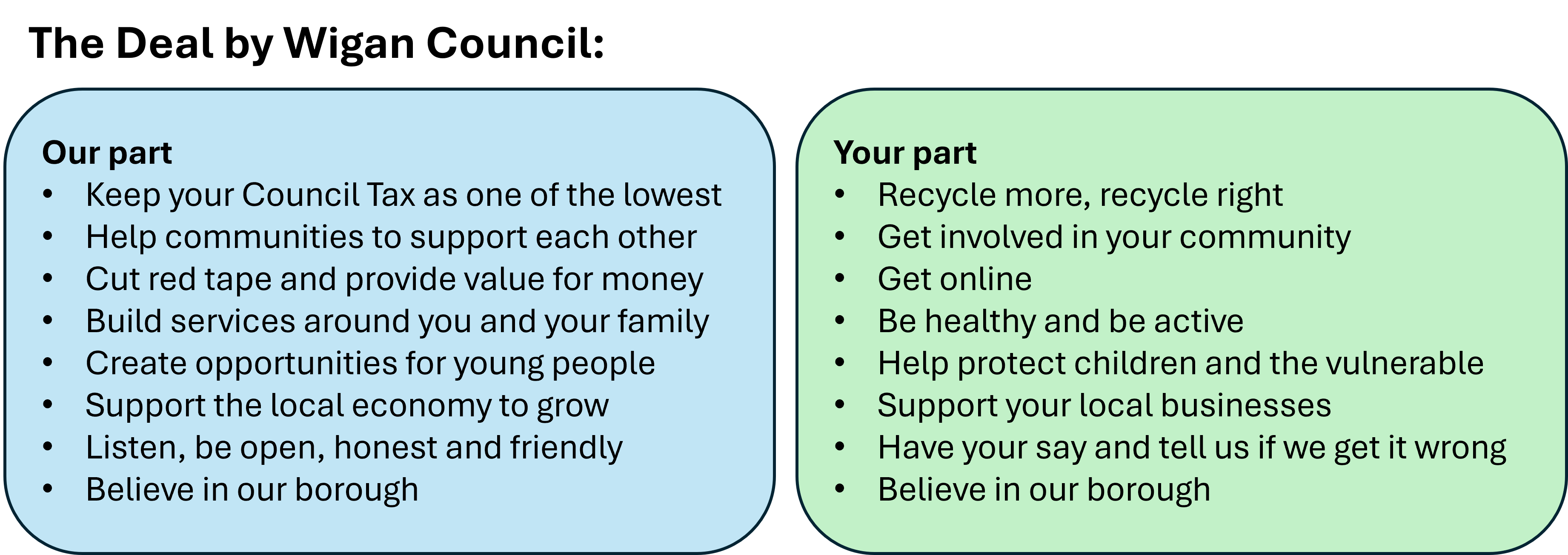

The Wigan Deal. In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, local authorities in England experienced severe austerity measures. Wigan was the third most affected council nationally, with its budget reduced by over 40% between 2010 and 2017. In response, the Council recognised that simply cutting services was unsustainable and, in 2014, launched The Deal: an informal agreement between the council and local residents and businesses to work together to build a better borough. At its heart, The Deal was based on a shift in mindset - a belief in the assets, strengths and potential of staff, residents and communities, and a willingness to embrace innovation and managed risk. It rested on four core components:

- Asset-based working - focusing on strengths rather than deficits

- Permission to innovate - empowering frontline staff to act creatively

- Investing in communities - supporting local capacity and resilience

- Place-based working - tailoring support around local neighbourhoods

Over time, this new social contract helped the council to stabilise finances, hold council tax at lower levels, maintain key services despite significant budget pressures, and contribute to improvements in health and life expectancy outcomes across the borough.

In Northern Ireland, a 2025 survey has reported that over half (51%) of people feel disconnected from health and social care services and care, with a similar proportion (48%) believing that no action they took would make a difference to pressures on the health service there.3 In response, as part of the Health and Social Care Reset Plan, the NI Executive has committed to “a renewed and concerted focus on prevention, health literacy, and empowering people to manage their own health; by beginning a dialogue with them about what health means to them and how they can help us to help them when they most need us”.4

As a first step towards this commitment, a roundtable discussion was hosted at Hillsborough Castle in September 2025, where senior health and care leaders, thought leaders, representatives from local government, the Community and Voluntary sector and leaders from wider Northern Ireland Government departments came together to explore the potential collaborative advantage of a new relationship with the public in delivering public sector goals.

The outcomes of that roundtable were captured in a report, People to Partners: Developing a Unique Approach for Northern Ireland.5 Recognising citizens as active partners in shaping health and social care, the report highlights the need for cultural and systemic change, stronger collaboration across government, and greater investment in co-production and community capacity. Central to its recommendations is the creation of a cross-government strategic framework to align policy, resources, and leadership around partnership with the public. By embedding this approach at every level, the report sets out a vision for a health and social care system built with people, not simply for them, moving from discussion to coordinated, cross-government action that places people at the heart of decision-making.

Ireland, meanwhile, has seen a significant deepening of its commitment to patient and public partnership within the health system over the last decade. The establishment of the HSE’s National Patient and Service User Forum in 2015 provided, for the first time, a national structure through which patients, carers and service-user advocates could contribute directly to service planning and policy development. This was reinforced with publication of the HSE Patient and Partnership Strategy, 2019-2023 and the publication of the Better Together Health Services Patient Engagement Roadmap in 2022, a system-wide framework designed to move engagement beyond consultation towards genuine co-design and shared decision-making.

Institutionally, the infrastructure to support this shift has continued to mature. Partnership is now increasingly recognised as a standard, built-in component of all major service development initiatives, rather than as an ad hoc activity. Patient and Public Partners have played a significant role in shaping the HSE Centre and Regional design under the Sláintecare programme, and most major programmes of work — including the Digital for Care Programme — now include patient and public representation on their steering and working groups.

The annual Patient and Public Partnership Conference has become a well-established event over the past three years, attracting more than 400 in-person participants and over 400 online attendees. A National Office for Patient and Service User Engagement has been established to coordinate policy, build capacity within services, and support consistent standards of partnership across the HSE, while a National Partnership Lead has recently been recruited and tasked with ensuring that the Regional and National Partnership Councils are implemented and run to a high standard.

At regional level, each of the six new Health Regions has appointed a dedicated, full-time Public Engagement Lead. These roles are intended to embed partnership in everyday practice - ensuring that local priorities, service improvements and reform initiatives are shaped collaboratively with patients, families and communities. Collectively, these developments reflect a deliberate evolution from ad-hoc engagement to a more structured, strategic and resourced approach to public partnership across the Irish health service.

Conclusion

In summary, redefining the social contract for healthcare is essential for creating systems that genuinely meet the needs of our public. By viewing individuals as active partners rather than passive recipients or consumers of care, we can foster a collaborative approach that emphasises shared responsibility and community strength. Trust is both the foundation and the outcome of building a system that does things with people: citizens must trust that their voices matter, and professionals and institutions must trust in the public’s capacity to shape solutions. Only through that reciprocal trust can we create a sustainable, responsive, and truly people-centred system. While challenges exist, prioritising genuine engagement and co-production is essential for achieving better outcomes and creating a sustainable healthcare future.

Summary

Health systems face mounting strain from ageing populations, chronic illness, and rising expectations. Traditional models of care are no longer sustainable. A shift toward partnership, prevention, and community-led approaches is essential to create resilient, person-centred systems that share responsibility for health and wellbeing across society.