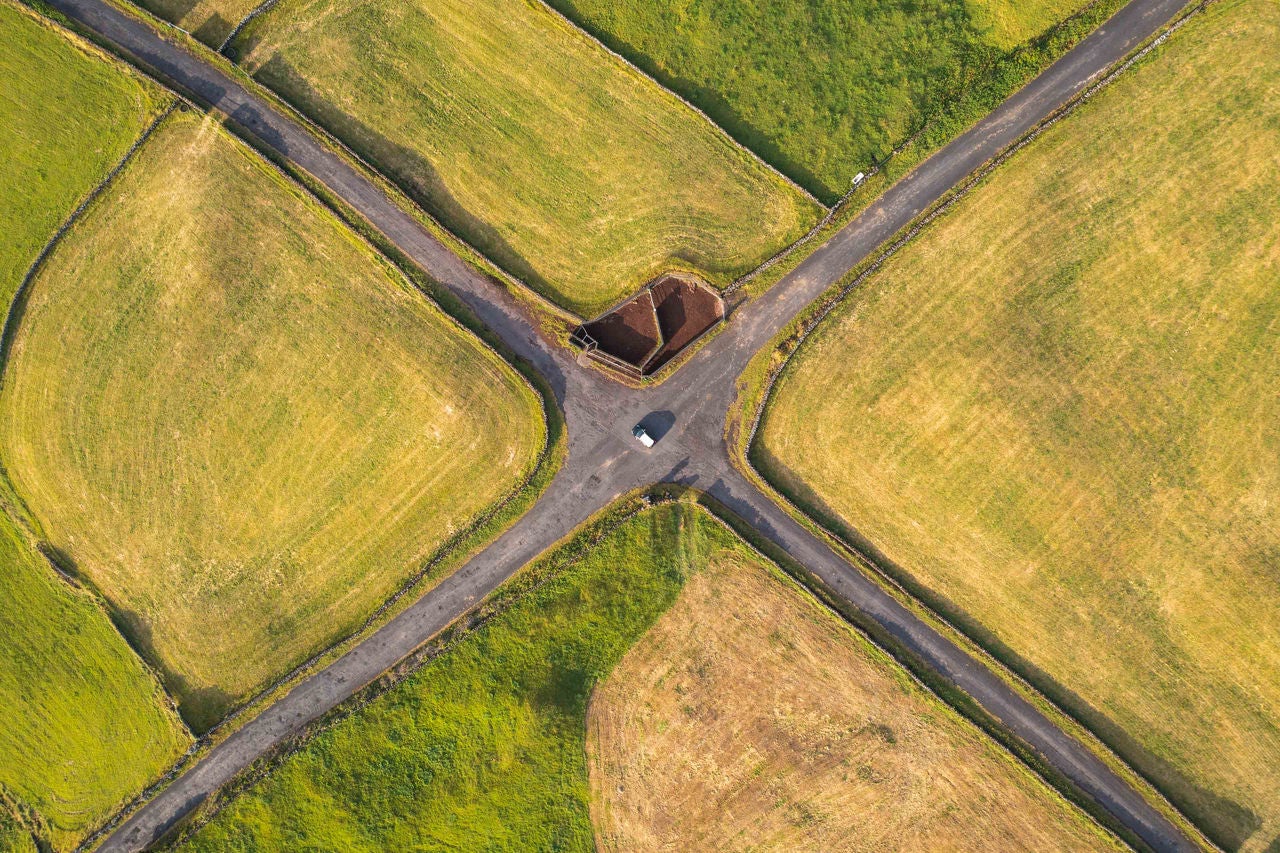

Al igual que toda infraestructura, la capacidad migratoria requiere una inversión deliberada, coordinación y compromiso durante años, si no décadas.

Por ejemplo, la construcción de viviendas en los Estados Unidos tarda un promedio de dos años desde la planificación hasta la ocupación31. La creación de marcos de reconocimiento de credenciales y vías rápidas para la obtención de licencias suele requerir varios años de negociación y aplicación. El acuerdo de enfermería entre Quebec y Francia, por ejemplo, tardó más de tres años en establecerse32. Los servicios de integración (formación lingüística, búsqueda de empleo, acercamiento cultural) necesitan años para funcionar de manera eficaz. La infraestructura social —la confianza y la aceptación que permiten la integración— puede tardar generaciones en madurar.

El cuello de botella no tiene tanto que ver con la demanda o la oferta como con la infraestructura de absorción.

A partir de ahora, los países pueden posicionarse para tener una capacidad significativamente mayor en las próximas dos décadas, cuando las necesidades demográficas alcancen su punto álgido.

El desafío de la capacidad de absorción

La infraestructura física supone un impedimento para la migración, al igual que las políticas o la demanda de mano de obra. Incluso antes de tener en cuenta los aumentos repentinos de la migración, la escasez de viviendas afecta a varias grandes ciudades receptoras, como Toronto, Dubái, Londres y Berlín. La infraestructura urbana no se diseñó para hacer frente a un rápido crecimiento demográfico y la construcción no puede adaptarse con la suficiente rapidez si no se aceleran las obras desde ahora mismo.

En 2023, Canadá añadió 5,1 residentes por cada nueva vivienda, en comparación con la media histórica de 1,933. Australia solo consiguió construir una vivienda por cada 3,2 migrantes en 2023 y una nueva propiedad por cada 2,1 migrantes en 202434. Alemania ha pronosticado que necesitará más de 2,5 millones de nuevas viviendas para 203035. Mientras tanto, los plazos de construcción son de entre 18 y 24 meses de media, lo que crea un desfase entre los picos de migración y la disponibilidad de viviendas.

Estas proporciones se traducen en decisiones reales: familias de cuatro personas durmiendo en una sola habitación, trabajadores cualificados que deciden no emigrar porque no encuentran vivienda, salarios que se consumen íntegramente en el alquiler, sin dejar nada para la integración. La infraestructura no es una fría estadística; se trata de si una familia invitada a cubrir la escasez de mano de obra puede construir una vida en una comunidad con viviendas, escuelas y servicios adecuados, o si al llegar se encuentra con las mismas carencias de infraestructura a las que ya se enfrentan los residentes actuales.

Es importante reconocer que estas presiones no solo limitan a los recién llegados, sino que también afectan a los residentes actuales, provocando un aumento de los alquileres, la saturación de escuelas y hospitales y el agravamiento del resentimiento político por la percepción de competencia por unos recursos escasos.

Las ciudades no pueden absorber más rápido de lo que pueden crecer la vivienda y los servicios. Si no se acelera la construcción a partir de ahora, estas deficiencias persistirán en el futuro. Independientemente de las necesidades del mercado laboral o de los imperativos humanitarios, la capacidad de absorción es una limitación vinculante para los flujos migratorios.

Dos ciudades demuestran lo que se puede lograr con una infraestructura habitacional bien planificada. El modelo de vivienda social de ingresos mixtos de Viena mantiene aproximadamente a 60 % de residentes en unidades subvencionadas con fondos públicos, lo que evita las espirales de asequibilidad que se observan en otros lugares36, mientras que las viviendas reguladas para trabajadores de Singapur alojan a 38 % trabajadores extranjeros gracias a un desarrollo coordinado entre el sector público y el privado37.

Cuellos de botella en el reconocimiento de credenciales

Un tercio de los inmigrantes con un alto nivel educativo en los países de la OCDE están sobrecualificados para sus puestos de trabajo, con tasas que alcanzan el 73 % en la República de Corea y el 57 % en Canadá38. No se trata de un desajuste de competencias, sino de fallos del sistema. Cada caso representa años de formación que se ven invalidados por la falta de reconocimiento de las credenciales, familias que viven con una fracción de su potencial de ingresos y países de acogida que desperdician el talento que dicen necesitar desesperadamente. Un cirujano conduce para Uber. Un ingeniero es repositor. Un maestro trabaja en el comercio minorista.

La OMS prevé un déficit de 11 millones de trabajadores sanitarios para 203039, pero miles de trabajadores sanitarios formados en el extranjero no pueden ejercer porque los procesos de reconocimiento de sus credenciales tardan meses o incluso años.

La optimización del reconocimiento de credenciales no es solo una cuestión de equidad, sino también una necesidad económica.

Los sistemas para hacerlo ya existen. La Ley de Reconocimiento de Alemania ha tramitado más de 383.000 solicitudes de cualificaciones extranjeras desde 2012, y los procedimientos suelen completarse en un plazo de tres meses40. Los refugiados patrocinados de forma privada en Canadá mostraron unas tasas de empleo en el primer año del 90 % e para los hombres, lo que supone 17 puntos porcentuales más que los refugiados asistidos por el gobierno41. Estos sistemas funcionan cuando se diseñan deliberadamente.

Volatilidad política y falta de coordinación

El desajuste entre las necesidades económicas a largo plazo y los ciclos políticos a corto plazo genera volatilidad. Las empresas no pueden desarrollar estrategias de talento a largo plazo cuando las normas sobre visados cambian con cada elección. Muchos ciclos políticos duran entre dos y cuatro años, mientras que las infraestructuras tardan años o décadas más en generar beneficios. La política migratoria cae en esta trampa. Se evalúa en función de los plazos electorales, mientras que sus efectos se extienden a lo largo de generaciones. Como observa Gregory Daco, economista jefe de EY, Ernst and Young LLP: "Siempre que se producen entradas migratorias netas fuertes y rápidas, tiende a producirse un rechazo populista. Estas rápidas entradas de inmigrantes suelen impedir una integración inmediata, lo que puede dar lugar a la idea errónea de que 'los extranjeros nos están quitando el trabajo'. No creo que ese sentimiento y sus implicaciones electorales vayan a desaparecer pronto".