Key rankings

Where to next?

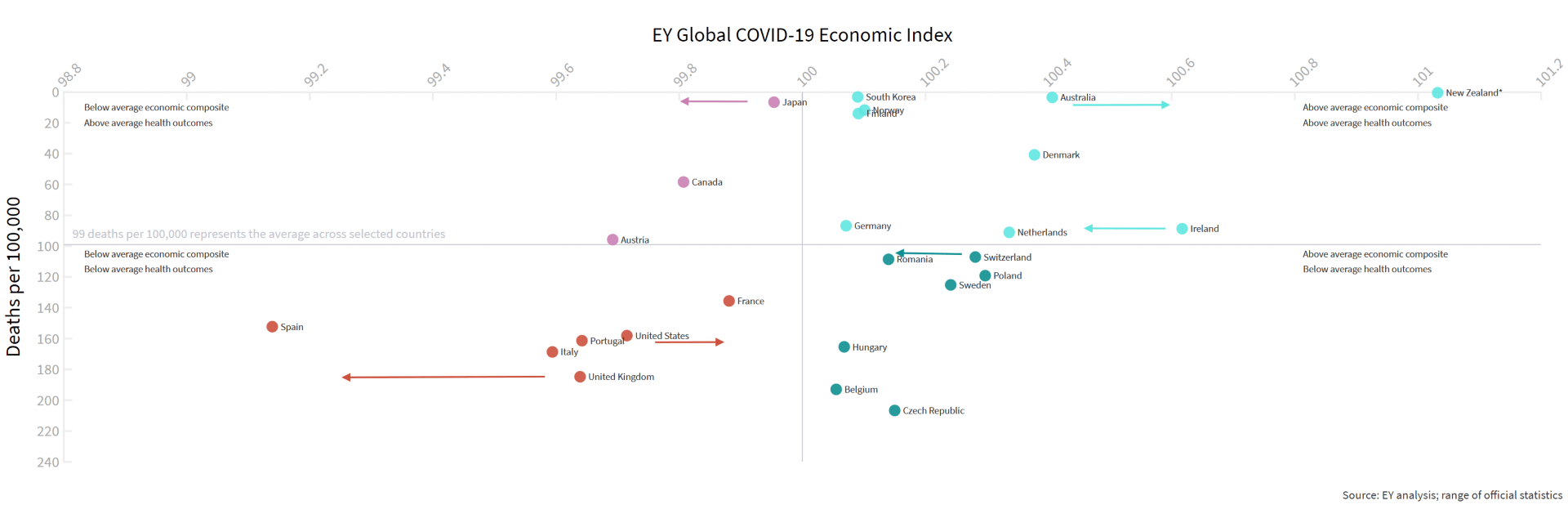

We expect it will be beneficial to update this framework as the virus and vaccine program evolves, countries stimulus programs change, countries re-enter lockdown and withdraw or instigate new policies which flow through to their balance sheets. For many countries, renewed waves of infection and associated lockdowns and restrictions, combined with weak balance sheets limiting the response, are expected to see their relative position deteriorate over the March quarter, as illustrated in Chart 2, below.

Australia, however, is not one of them. In fact, we expect over the March quarter to see Australia outperform all other countries in the scale of improvements - strong momentum, a broadening recovery, improving consumer confidence, easing health restrictions and continuing policy support should support this improvement.

Expected movement in rankings across the March quarter

*Due to data limitations, it has been assumed that New Zealand has the same financial and non-financial corporation health as Australia. Countries selected based on data availability only – as a consequence most are developed countries. Data as at 10 March 2021.

Sources: EY analysis of Oxford Economics, WHO, IMF & Macrobond data

The United States is also expected to make a large jump as a result of improving economic outcomes, the roll out of the vaccine and increased fiscal stimulus. Importantly, our framework will capture the worsening government fiscal position which will see the United States Government net debt exceed 100 per cent of GDP. Other notable improvers are expected to be New Zealand and South Korea – though to a lesser extent.

Some economies, in contrast, are expected to lose ground relative to the rest of the countries. Of note, is Japan which implemented a state of emergency across most urban areas for much of the March quarter – which constrained consumption at restaurants, bars and other businesses after 8pm. One of the key lessons of 2020 is understanding of how quickly and severely lockdowns hit economic activity. Japan will be keen to get on top of the health crisis ahead of the looming Tokyo Olympics.

Ireland, Switzerland and the United Kingdom are also expected to underperform reflecting stringent lockdowns put in place across the United Kingdom and much of Europe.

Australia is sitting at the top of the table and expected to stay there

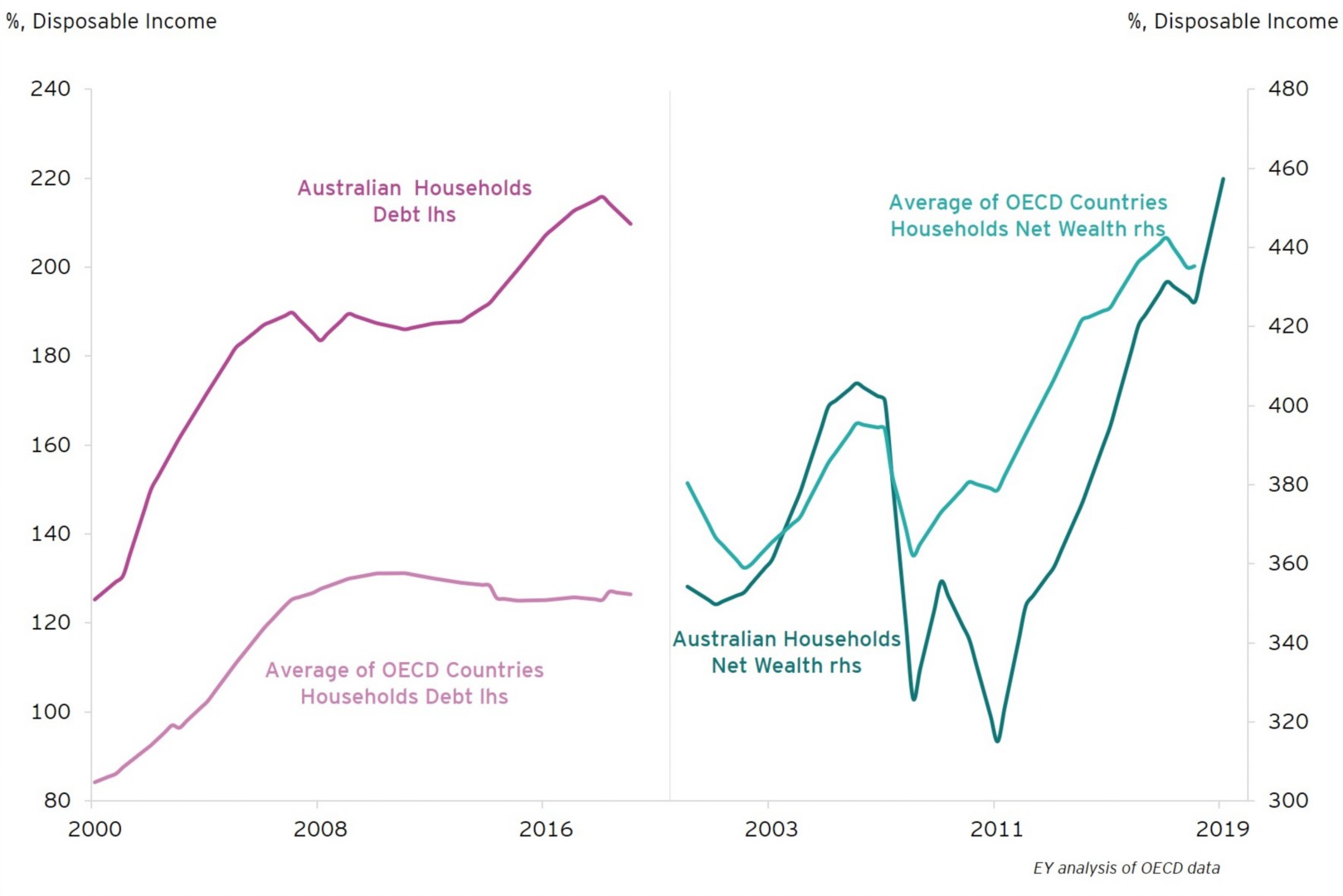

Interestingly, the general feel coming in to 2020 was that Australia needed to be worried about both its household balance sheets, and its government balance sheets. The Federal Government was pushing strongly to return a budget surplus and markers were interpreted to suggest some level of pending economic stress, including as a result of relatively high household debt.

However, what we found was that comparably, we are in a much stronger position than we thought and both government and household balance sheets have been relatively resilient. As Chart 3 below highlights, while household debt in Australia is relatively high, household net wealth – which accounts for Australia’s high debt levels – is in line with our peers.

While Australia was worried about rising household debt levels, rising net wealth put household balance sheets in relatively good shape

Based on Australia’s EY Global COVID-19 Economic Index, Australia is likely to outperform every country in the ranking except New Zealand by the time March quarter 2021 data is published – placing us in an enviable position for ongoing economic recovery. Such a position at the top of the rankings should also limit economic scaring in Australia, relative to other economies and compared to our last recession in the 1990s.

The Vice-Chair of the United States Federal Reserve, Dr Richard Clarida [1]identified three critical components as being the differentiator for why economic scarring from COVID-19 wouldn’t be as bad as during the GFC: A fiscal response “scaled appropriately to the size of the shock… we did have the space [to respond because America is] a reserve currency country and we deployed it”; a strong monetary policy response; and “[America] went into this with a very well capitalised and very liquid banking system, which was not the case 15 years ago”.

Similarly for Australia where healthy balance sheets underpinned fiscal support scaled appropriately to the size of the shock, an strong monetary response and well capitalised and liquid banks.

So why aren’t Australian businesses taking more risk?

Australia has not only seen an impressive health response, strong economic outcomes and the resilience that our balance sheets provide, but Australian businesses have access to cheap and easy credit and buoyant capital markets. Moreover, EY’s latest Capital Confidence Barometer[2] shows that Australian firms expect revenue and profitability will be back to pre-pandemic levels this year or next.

Despite all this, private business investment continues to disappoint; contracting by 5.1 per cent through 2020 despite policies to promote investment.

One factor explaining this lacklustre investment climate is that hurdle rates for investment in Australia remain high. Given hurdle rates are a combination of the weighted average cost of capital – which has clearly fallen, and risk appetite, what this tells us is that the risk premia remains elevated, and unnecessarily so given our analysis shows that Team Australia delivered and that Australia is well placed to continue to outperform as recovery continues.

That knowledge, especially as we continue down the vaccine rollout path, should be giving business the confidence to move into the future with certainty and pull the trigger on bolder investment decisions, which as Reserve Bank of Australia Governor Phil Lowe said, means invest, expand, innovate and hire.

Australia ticks the boxes for many of the preconditions for businesses to invest and hire, and for consumers to go out and spend. Consumers are doing their part, but improved investment appetite by corporate Australia would provide a broader base for recovery. Governments should see this as a great opportunity to innovate and legislate, an opportunity to push Australia’s current outperformance even further, to celebrate out-performance for years to come.

Related article

Methodology

*Our composite methodology draws from publicly available data that provides the greatest scope for comparison across countries. Where countries are not included in the EY Global Covid-19 Economic Index is because there is insufficient data available to make a reasonable comparison. In regard to New Zealand, listed corporate balance sheet data is not publicly available. We have used Australia’s rankings as a proxy for New Zealand on the basis that Australian financial institutions and their subsidiaries are dominant in the financial sector, and a large proportion of listed non-financial companies are also foreign owned.

**The composite methodology comprises:

- 50 per cent weighting for economic performance – with a 25 per cent weight to GDP and a 25 per cent weight to employment

- 50 Per cent weighting across five balance sheets with 10 per cent allocated to each balance sheet. Included is Government Net Debt per cent of annual nominal GDP; Central Banks assets per cent of annual nominal GDP; Household balance Net wealth as a per cent of annual nominal GDP; Financial sector regulatory capital to risk weighted assets; Non-Financial sector Net wealth as a per cent of annual nominal GDP.

Summary

Australia’s economic, health and political institutions have come together like never before and executed a response to the current pandemic that is among the best in the world. It means that while many challenges remain to be solved, relatively speaking Australia is in a great position to recover quickly and outperform global peers, not just in the short term but for years to come.