A holistic view of healthcare stakeholders – pharma companies and other healthcare manufacturers, hospitals and physicians’ practices, health insurers and regulatory authorities – is needed to understand and pull the levers that will enable green health.

A recent WHO report calls for the urgent need to improve healthcare waste management practices, especially in light of the pandemic response. For example, over 140 million test kits with a potential to generate 2,600 tons of non-infectious waste (mostly plastic) and 731,000 liters of chemical waste (equivalent to 1/3 of an Olympic-sized swimming pool) have been shipped across the world from March 2020 to November 2021 - threatening both environmental and human health. And yet, those numbers only account for UN procured tests - a small fragment of the significantly larger global procurement pool: in the same time period, a total of 1,7bn tests have been conducted in Europe alone. The UN agency calls for “significant change at all levels, from the global to the hospital floor”.

Given the growing urgency around climate change and climate-friendly health practices, healthcare stakeholders must play their part in protecting both human lives and our planet. A holistic view of healthcare stakeholders – pharma companies and other healthcare manufacturers, hospitals and physicians’ practices, health insurers and regulatory authorities – is needed to understand and pull the levers that will enable green health and, ultimately, a sustainable industry. In this paper, we explore the environmental aspects of sustainability across the healthcare continuum and propose approaches for greener health practices.

Chapter 1

Together we build

Establishing green health practices in Switzerland

In Switzerland, the larger debate on sustainability still tends to neglect the burden the healthcare system places on our environment and its contribution to climate change. However, pioneering Swiss health organizations are starting to address the topic themselves. By measuring their own footprint, they are creating a culture of transparency; taking responsibility; and seizing the opportunity to capitalize on quick wins.

Damaging climate effect

7 hoursof anesthesia with desflurane emits as much GHG as a return car journey from Zurich to Beijing

One example is the substitution of standard anesthetic gas for climate-friendlier alternatives in Swiss hospitals. The often-used desflurane is about 20 times more damaging in terms of emissions than the alternative sevoflurane, which is still a potent greenhouse gas (GHG). Emissions from seven hours of anesthesia with desflurane (2 l/min) are equivalent to a 15,700 km car journey. That would be about the same as a return car journey from Zurich to Beijing – and back.

The health industry has identified quick sustainability wins and many companies have already taken steps to adjust energy, water usage and waste management. To realize the full potential of ecological transformation, the entire healthcare community will need to identify and quantify all levers across the sustainability spectrum: from sourcing energy and seeking operational efficiencies, to procuring more sustainable medical supplies.

Swiss health players have started with initial individual activities that can offset limited carbon emissions. However, when zooming into the current sustainable initiatives of actors within the Swiss health system, we see a patchwork quilt of initial green practices. A more thorough economic analysis can highlight what financial value additional green practices might yield, both in the short and long term, spotlighting essential conditions for driving systematic and sustainable changes, such as multi-stakeholder involvement and collaboration.

Chapter 2

Counting contributions

Assessing Swiss health stakeholders’ current green practices and unrealized potential

In this chapter, we explore key climate levers across selected stakeholder groups in Switzerland: big pharma, hospitals, payers and regulators.

1. Big pharma is driving sustainable efforts with long-term net-zero ambitions

Acknowledging that over 70% of health care emissions stem primarily from supply chains, pharma companies are one of the largest contributors to the healthcare climate footprint, especially when combined with other supply chain-related emissions like procurement of non-medical equipment.

In addition to sustainable procurement practices and a switch to renewable energies, pharma companies can green their operations by optimizing high-footprint processes associated with high energy and water usage for heating, insulation, and cooling, as well as improving inefficiencies in logistics and transport. Aiming for innovative circular approaches could help in tackling packaging and recycling waste and improve pharmaceutical contamination in terms of drug disposal and water supply.

Looking at the pharmaceutical footprint in Switzerland is crucial not only for assessing the domestic health climate footprint but also the international impact of the industry. Switzerland is home to Novartis and Roche, two of the leading global pharmaceutical companies, and an important hub for many more.

Like many other pharma companies, both Novartis and Roche have committed to a long-term transition toward net-zero carbon emissions by 2040 and 2050, respectively, acknowledging their indirect, but significant, environmental impact on the value chain.

In addition to the efforts of individual pharma companies, a more wholesale industry-wide sustainability effort has emerged. For instance, major players including Johnson & Johnson (J&J), Sanofi and AstraZeneca have recently joined “Energize”, a collaborative program to increase access to renewable energies to hundreds of suppliers across the pharmaceutical chain. Equally, other healthcare manufacturers, for example suppliers of medical devices, can have a significant impact, too, when taking responsibility through green practices – both upstream and downstream. In Switzerland, J&J has recently launched a recycling initiative, helping Swiss hospitals to reduce the amount of waste in operating theaters. Within four months, J&J collected more than 2,800 disposable medical instruments, recovering 87kg of valuable metals such as steel, titanium, aluminum and copper, and recycling 220kg of plastic.

Some of these green practices have been further accelerated by the UK’s National Health Service (NHS). With central buying power for the UK’s primary healthcare provision, the NHS incentivizes pharmaceutical companies to rapidly accelerate sustainability initiatives and comply with potential future NHS requirements. These include compulsory reporting from suppliers and inclusion of carbon accounting metrics in procurement exercises.

While some of the levers require significant investment and multi-year planning, other green practices can be categorized as quick wins. One example would be replacing the currently mandated paper leaflets in drug packages with digital alternatives. However, regulatory guidelines often hinder pharma’s efforts to capitalize on similar “low hanging fruits”. Furthermore, green incentives are not yet attractive enough for pharma companies to offset profit deficits. Government and industry stakeholder will need to ask: what incentives and regulatory frameworks would incentivize an even more significant and earlier transition to net zero?

2. Hospitals are starting to capitalize on initial “quick wins”

A typical hospital consumes almost three times more energy than a commercial building of similar size. Various studies suggest that hospitals are responsible for approximately one-third of the total healthcare carbon footprint.

The research initiative “Green Hospital” analyzed the climate footprint of 33 Swiss hospitals to assess the most significant climate levers of hospitals and how environmental efficiency can be increased without cutting back on the quality of health services. In 2021, they found that around half of the hospitals could double their environmental efficiency without reducing their output.

Biggest inefficiencies were identified in areas such as heating/cooling as well as in medical supplies for instance the reliance on cheap and sterile single-use plastics. Widely untapped potential in terms of hospitals’ energy usage includes the possibility of leveraging waste heat or renewable energies. There is also an urgent need for action on levers, with some of the relatively larger environmental impacts coming from building infrastructure and catering.

Many hospitals, both public and private, have started to implement green practices stretching across the discussed climate levers. Here, we share some examples:

- Starting to exploit some of the biggest inefficiencies and quick wins, Basel University Hospital completely relies on electricity from renewable energies, cut down the amount of food waste and replaced disposable tableware for takeaways with a reusable eco-friendly alternative. Also, circularity principles and energy-saving measures are implemented in the hospital’s core business. The radiology department, for example, scientifically examined energy consumption of its MRI & CT fleet. The hospital’s 3D print lab collects, shreds and reuses plastic of old anatomic models to produce new ones.

- Hirslanden, Switzerland’s largest private hospital group with 17 hospitals, has set its own goal to become carbon neutral, albeit without specified scopes, and to send no waste to landfill by 2030. As part of their strategy, they tackle catering by recycling leftover food, adjusting dish sizes and disposing of non-recyclable leftovers in biogas plants or bio washers, which in turn generates new energy. Significant initiatives in terms of energy procurement include replacing older cooling machines and gas heating with geothermal heat pumps that emit significantly less CO2.

- Several hospitals, such as the Bürgerspital Solothurn or Inselspital in Bern, are currently modernizing or building new facilities to adapt to new sustainable requirements. Considering the buildings’ long useful life, investment is expected to be profitable despite significant upfront costs.

Hospitals’ current varying green practices have been driven predominantly through bottom-up initiatives. Claudia Hollenstein-Humer, Head of Sustainability & Health Affairs at Hirslanden AG emphasizes that: “Sustainability is a topic that matters to all of us. Our employees are very active to drive change here, but I believe that patients also think about sustainability when choosing a hospital.” On top of individuals’ motivation, other key drivers for existing green initiatives are goals set by authorities and economic reasons, where applicable. However, the latter is also the biggest showstopper in realizing hospitals’ full ecological improvement potential due to cost pressures, lack of incentive policies and legal requirements.

3. Payers are yet to exert their influence on health players

Health insurers could play an equally important role in the fight against climate change. While their impact comes less from minimizing their own carbon footprint, they play a key role in incentivizing pharma, providers, and patients to adopt greener health practices. However, Swiss health insurers can only act within the boundaries of the regulatory requirements defined by the Federal Office of Public Health.

So far, limited focus on sustainability has been identified besides efforts from Swiss health insurance companies such as CSS, EGK and Sanitas to donate to climate projects and reduce their own greenhouse gas emissions by transitioning to green power and buildings. CSS, for example, took measures to increase the sustainability of its properties, reducing CO2 emissions by almost a quarter per year. Other initial steps are seen with brokers that exploit the health insurers’ limited focus on sustainability by promoting “green services”, reinvesting a share of their commission into environmental projects such as planting trees.

Their biggest lever is yet to be pulled through the payers’ influence on others, for instance through a stronger focus on prevention and by incentivizing healthy lifestyles. Especially within the realms of the supplementary health insurance which allows insurers a higher degree of freedom in offering innovative, sustainable insurance product offering. However, health insurers could also influence sustainability activities upstream in the value chain by jointly lobbying and increasing the pressure on pharma companies and hospitals. In Germany, the health insurer AOK has initiated first steps toward more stringent environmental protection with a separate tender for antibiotic active ingredients, where the focus has been not just price but also the manufacturer’s sustainability approach, such as thresholds on pharmaceutical residues in production wastewater.

Acknowledging the uniquely positioned government-sponsored universal health coverage in the UK, the NHS committed to reach net zero across the entire scope of emissions by 2045, with concrete milestones and activities to achieve its goals. The NHS was able to mobilize global healthcare and tech companies such as J&J, AstraZeneca, Microsoft and Apple in pledging to decarbonize the NHS supply chain. In an open letter to 80,000 global suppliers, the NHS urged them to act now and decarbonize their operations.

For many years, large Swiss insurance groups such as Swiss Re or Zurich Insurance Group have taken sustainability criteria into account in their business processes, e.g., through sustainable underwriting policies or responsible investment strategies. Compared to those multinational players, the Swiss health insurance market has been lagging. However, as Tobias Caluori, Head of Product Development at Sanitas, points out: “Specific CSR aspects such as health prevention services for their customers have been part of the health insurers’ value proposition. More recently, several market players shifted their strategic focus from being a pure “financial risk insurer” to positioning themselves as “health partner” of the patients by extending those services even further.”

Patients themselves are another vital driver in accelerating a push toward green practices, especially when it comes to choosing payers and providers. However, substantial demand has been limited so far. Mr. Caluori notes that “unlike in other industries, CSR has not been a critical decision factor so far when it came to choosing a health insurance. Above all, patients want a successful recovery from health issues and financial security. However, with the rising awareness for ecological and social aspects in society, CSR-focused customer segments could create demand for sustainable insurance products and services in the future.”

4. Slow progress from Swiss health authorities compared to other countries

Without playing down the responsibility and potential of each player within the health industry, the government might have the biggest levers with its ability to set the rules for climate-friendly healthcare. With the UK trailblazing the path to become the world’s first net-zero national health service, other European nations are following suit.

At COP26, seven European nations – Belgium, Germany, Ireland, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain and the UK – announced substantial health commitments. Next to the UK, also Spain and Belgium committed to a net-zero ambition before 2050. Together with the global NGO “Healthcare without Harm in Europe”, three health authorities – the Netherlands, Italy and Portugal – started “Operation Zero” to analyze their health systems’ respective climate footprint and outline roadmaps toward net-zero carbon emissions.

European examples indicate a strong trend and emphasize the importance for Swiss regulators to kick start the push toward a sustainable health system in Switzerland. The right regulatory framework would ignite and enable all stakeholders to realize their fair share of sustainable activities through new sustainability legislations and incentivization schemes at a national level. And most importantly, the option that is currently being discussed among different regulators: to set carbon targets, and, for example, impose carbon tax based on health industry benchmarking.

Chapter 3

Matching supply and demand: a case study

EY and FHNW School of Life Sciences illustrate the potential impact on carbon savings by balancing supply and demand of a popular drug and a common surgical intervention

Swiss statistics counting the number of medical treatments reveal astonishing regional and cantonal differences, indicating imbalances in supply and demand. Until now, evaluations have been limited mostly to pure purchase/treatment frequencies and (sometimes) their associated costs. The results of such analyses have fueled the discussion on misplaced incentives for volume-based reimbursement schemes, giving rise to concepts like “choosing wisely”, “value-based healthcare” and “capitation”.

However, current concepts often lack a holistic stakeholder view. One important, but unrecognized aspect is the quantification of potential negative environmental impacts stemming from an inefficient matching of supply and demand.

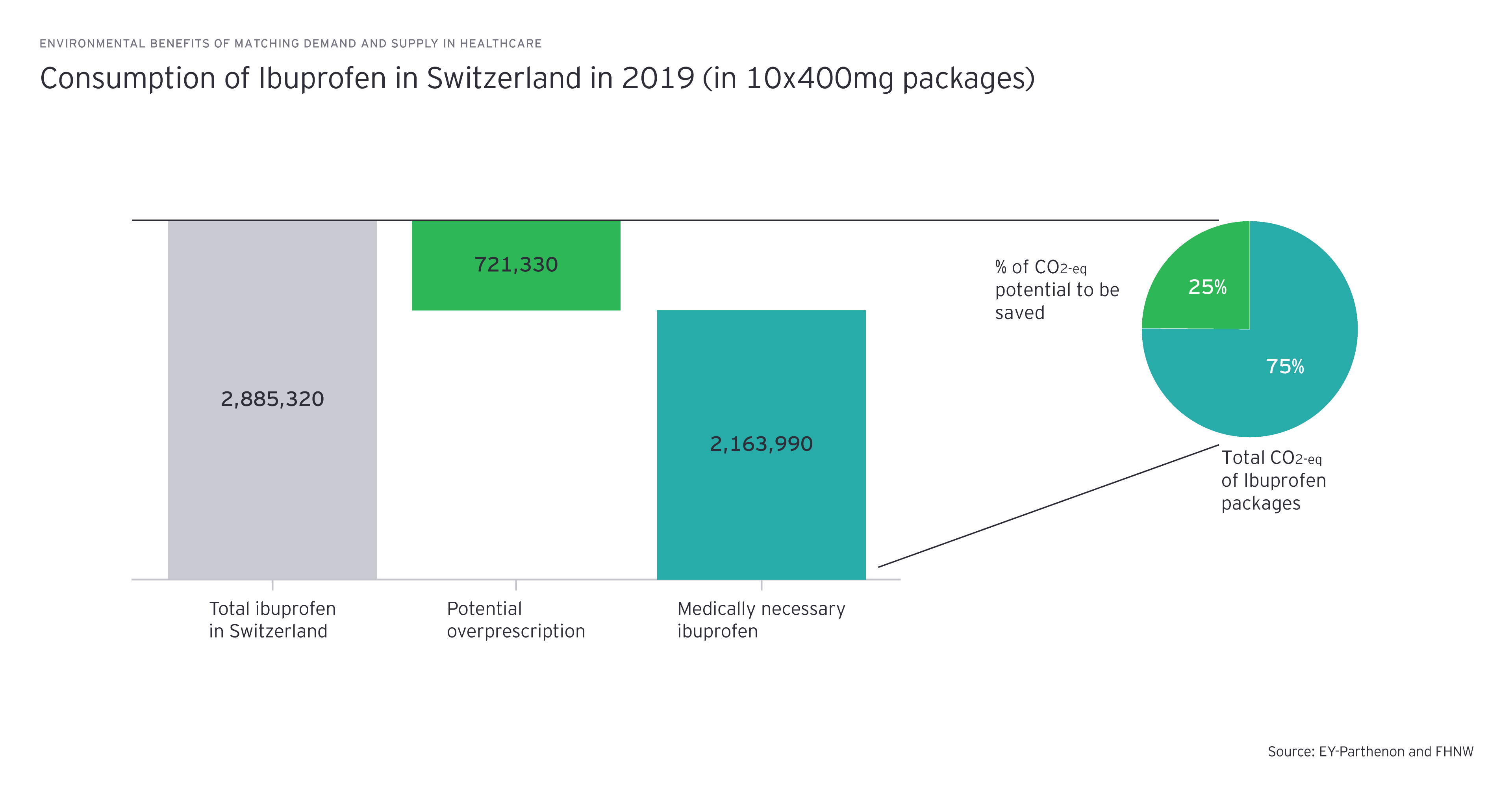

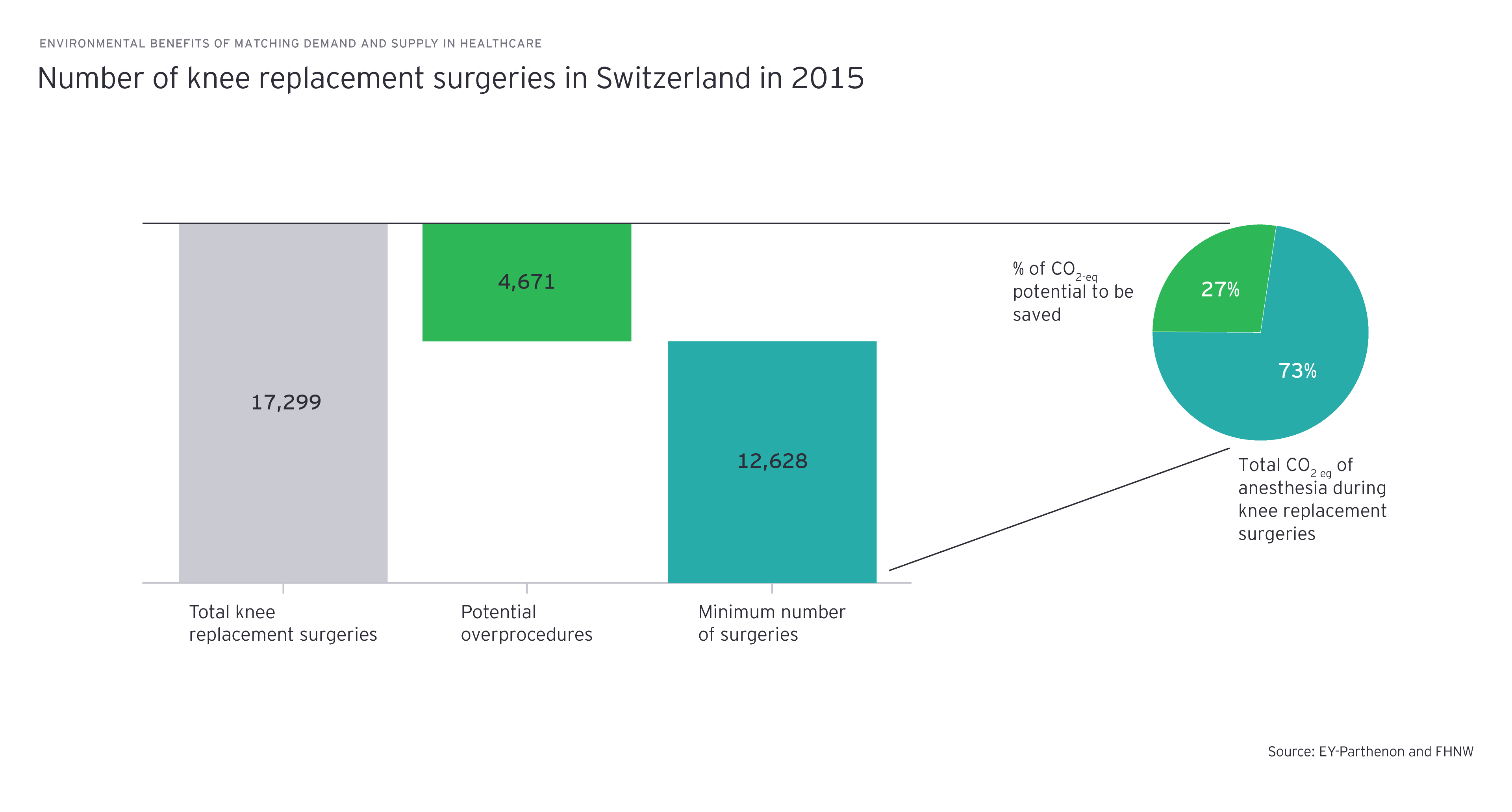

EY and FHNW School of Life Sciences want to demonstrate that a better coordination of supply and demand of medical treatments in Switzerland would not only generate cost-savings, but could also lead to substantial environmental benefits. While data on the environmental impact of medical interventions is limited, we have chosen two examples where data on the intervention’s variance of purchasing and its carbon footprint is available: Ibuprofen, one of the most prescribed and purchased non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in Switzerland, and knee prothesis, a widely used standard elective-surgical treatment.

Our case study is based on two Switzerland-specific variance plots:

- Ibuprofen: Pharmaceutical product purchases billed to the main Swiss health insurer varied from under -25% to over +25% of the Swiss average in 2019. For our case study, we assume the variance of all pharmaceutical purchases is reflected identically in the ibuprofen purchases as no data on ibuprofen-specific variances are yet available. Ibuprofen accounted for 2.4% of total pharmaceutical purchases in Switzerland in 2019 (third most purchased drug).

- Knee prosthesis: The total number of knee replacement surgeries ranged from 1.84 to 4.33 cases per 1,000 inhabitants, translating into a variation of -27% to +71% of the Swiss average in 2015.

Science still has some catching up to do when it comes to accurately quantifying the green potential of the healthcare sector. This is especially the case in assessing environmental impact of specific treatment schemes or procedures. Lifecycle assessments (LCAs) assess the greenhouse gas intensity, expressed as CO2-eq, or, more broadly, the total environmental impact of a product or service. LCAs assess the carbon savings of a specific product, but only exist for a few drugs and surgical interventions.

We have chosen the two examples for which profound LCA data exists:

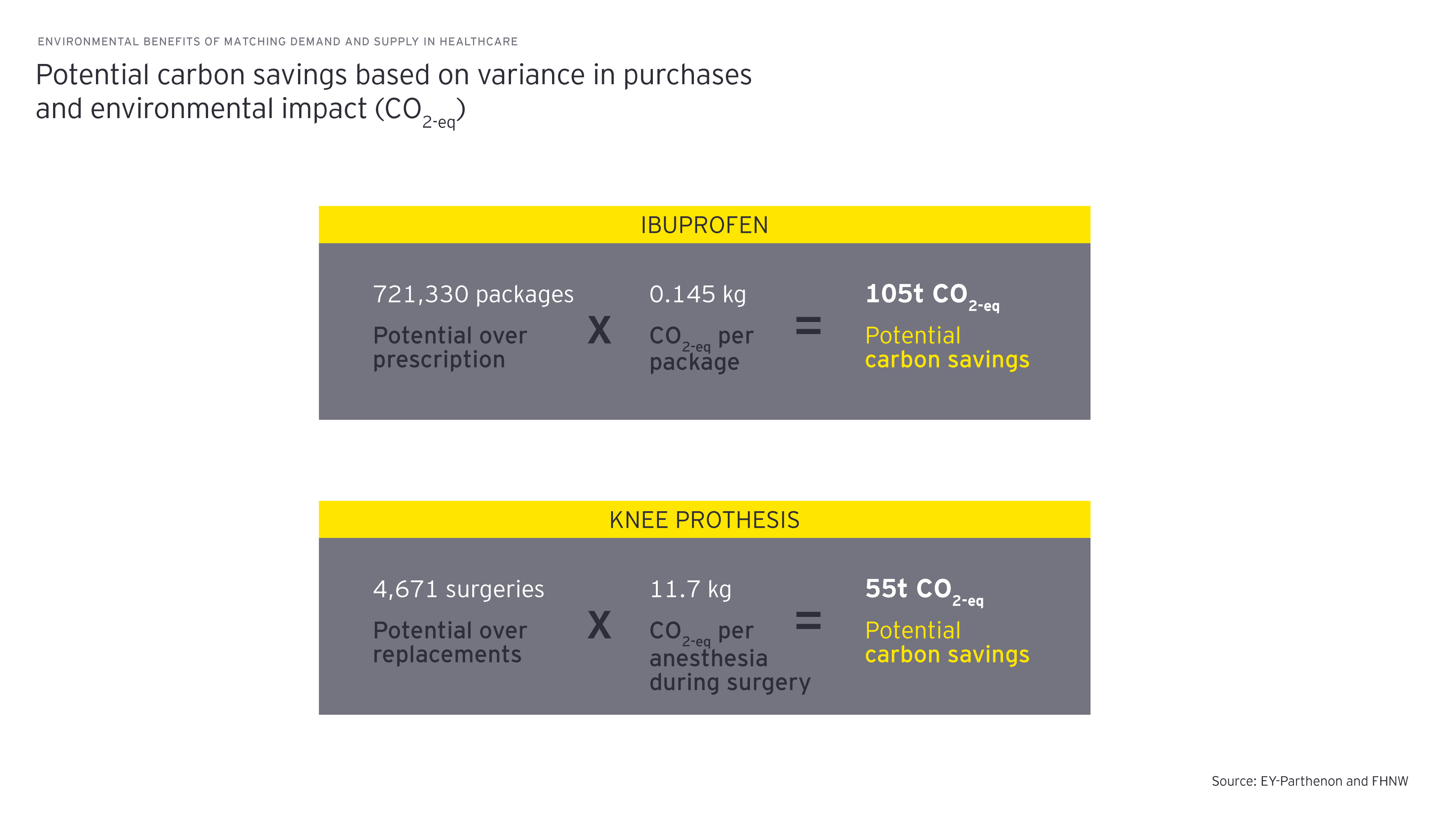

- One standard pack of Ibuprofen (10 x 400mg) accounts for 0.145 kg CO2-eq.

- The anesthesia footprint of a knee replacement surgery generates 11.7 kg CO2-eq (the mean value in the EU), depending on the type of anesthesia and gases used.

Environmental benefits of matching demand and supply in healthcare

We estimated the maximum potential of carbon savings, assuming that in each case only as many medical treatments are taken as in the lowest purchasing region (per capita). Our analysis is based on the regions’ variances in treatments and the corresponding global warming potential (GWP) for (1) ibuprofen and (2) anesthesia during knee prosthesis surgery.

If the volume of purchased ibuprofen could be reduced to the level of the canton with the lowest consumption, Switzerland could save 105t CO2-eq per year.

Similarly, if the number of surgeries for knee replacements could be reduced to the level of the canton with the lowest intervention rate among its residents, 55t CO2-eq could be saved, and that is only accounting for the (rather small) anesthesia-related environmental effect. Still, this is as much as the emissions per passenger for 55 flights from Zurich to the Canary Islands and back.

It should be noted that the strict CO2 lens that is applied in this case study neglects additional environmental damage such as micropollutants from medication residues in wastewater or resource depletion due to single-use medical devices. The multitude of above-mentioned environmental effects should also be considered when conducting comprehensive environmental impact analyses.

The environmental impact must be factored into more comprehensive healthcare considerations.

While these examples provide a first insight into the environmental benefits of balancing supply and demand, the findings emphasize the importance of accounting for the environmental impact in more comprehensive healthcare considerations. To realize its full potential, these implications need to be factored into financing and reimbursement schemes incentivizing prevention, value and outcome instead of volume or fee-for-service transactions.

Next, further studies are needed to fill knowledge gaps, including:

- Assessing LCAs for whole drug baskets and most frequent and relevant medical procedures

- Estimating the environmental co-benefits of prevention and lifestyle measures

- Investigating how regional differences in healthcare use emerge

Chapter 4

Incentivizing green health

Six levers to encourage progress toward net zero in healthcare

Switzerland’s potential for a net-zero healthcare system needs to be unleashed. To amplify existing initiatives, six powerful levers can be pulled. Their impact and reach rely on the collective involvement, support, and ambition of multiple players, rather than simply individual stakeholders.

Although Swiss healthcare stakeholders are beginning to establish green practices, the discussed levers will have to be pulled to catapult healthcare toward our collective sustainability targets. Each player carries a unique responsibility to contribute to the transformation. Yet, it is only by building together that we will ring in lasting changes that protect both lives and the planet. We believe that all actors can begin now with these three steps:

- Quantify “emission hotspots”, conduct an economic evaluation of your levers and outline your emission roadmap

- Innovate your processes and solutions across organization and procurement

- Partner up to realize the potential that requires a collective switch to green practices, jointly advocate for systematic changes to stimulate green practices and catalyze collective action

Summary

Healthcare used to enjoy immunity from the clamors of climate change. Now it’s not a question of whether but rather how quickly and how much healthcare can adapt to become a sustainable global industry. Pulling individual levers will have the biggest impact if stakeholders catalyze collective action.