1

Economic overview

Relying on improved household and business confidence to fuel a private sector-driven recovery.

The Australian economy stabilised through the September quarter. Health restrictions were eased, income support flowed and many businesses were able to reopen – but the recovery has been uneven, especially in Victoria. To date the greatest impact is on the young, females, small businesses and sectors like tourism directly impacted by restrictions.

The latest forecasts from Treasury are for the Australian economy to shrink by 3.75 per cent in 2020, and then rebound by 4.25 per cent in 2021. This strong rebound still leaves the economy smaller at the end of 2021 than it was at the end of 2019. While this may sound like a ‘V’ shape recovery, it’s not. The most likely recovery profile remains a ‘saw-tooth’ – its peaks and troughs dependent on the unfolding health crisis, fiscal response and border openings and consumer and business confidence.

The outlook for households remains challenging. After peaking in July, the unemployment rate has fallen, but momentum in job recovery is slowing. Unemployment is expected to rise from the current level of 6.9 per cent, to a peak of around 8 per cent by the end of the year. Further job losses are also likely going into 2021 as JobKeeper winds down.

Excess capacity in the labour market is expected to linger for some years, weighing on already weak wages growth. Constrained households have benefited this year from direct support payments, early access to superannuation and loan repayment deferrals. This support has not only enabled households to meet living expenses, but also to pay down debt and boost savings. However, in the December quarter, households will receive $20 billion less in direct support than the September quarter, with further tapering over 2021.

With the rise in disposable income in the June quarter unlikely to be repeated, households will have to adjust to lower incomes. The question is, will they plug the gap with savings and smooth consumption, or pare back spending and continue to build financial buffers? Consumers appear to be reining in spending. September’s retail trade data showed the second consecutive monthly decline in spending. Payroll data also suggests that, as companies lose direct support, insolvencies may rise over the year ahead, especially in small businesses.

The Government’s desire for a business-led recovery is contingent on companies investing and hiring. But, while confidence is nearing pre-COVID levels, capacity utilisation in September was just 76.9 per cent, well below the long-term average.

Credit data also suggests firms are sitting back and taking stock. Non-financial business credit contracted for four consecutive months between May and August, with firms boosting deposits and shoring up cash flow.

The RBA has made it clear that record low interest rates are unlikely to rise in the next three years. The RBA appears to be more comfortable with the prospect of lower interest rates driving up asset prices, particularly house prices, with RBA Governor Lowe arguing this can help financial stability by reducing the likelihood of problem loans.

In general, house prices have remained resilient throughout the crisis. After falling for five consecutive months, national dwelling prices turned in October and are now just 1.7 per cent below April levels and 2.0 per cent below their 2017 peak. This, in conjunction with low interest rates, supported first home buyers and encouraged high quality borrowers to draw down on credit. However, falling net-migration is reducing demand for housing, and the long construction lead time on new housing, particularly units, means new supply is still coming to market. Meanwhile, investor interest in residential property has fallen in the face of rising vacancy rates and falling rents.

Loan deferrals have temporarily supported the housing market but, as they come to an end, default concerns rise. Banks have assessed that around 15 per cent of deferred loans are at risk of not being able to resume repayments when the deferral period ends.[1]

While the near-term outlook for the Australian economy is uncertain, the Government has plenty of scope of for additional fiscal support. Importantly, medium-term prospects remain positive, particularly once borders open. Although population growth is expected to be weak this year and next, Australia remains a desirable destination for skilled migrants. The rise of Asia’s middle class, not just China’s, will continue to support demand for high-quality Australian goods and services.

New Zealand

In New Zealand, where each of the major Australian banks has operations, the economy contracted by 12.2 per cent over the June quarter. This was the largest quarterly contraction on record, marking the start of a technical recession. Economic activity has since recovered as restrictions have eased and Government support has cushioned the blow. Indeed, household spending has been quite solid while demand for housing and house prices have continued to accelerate.

Like Australia, New Zealand is facing a number of challenges, the unwinding of income support, as well as the need to safely open up international borders and allow for the return of tourists and importantly migrants. The labour market held up well over the June quarter, supported by the government’s wage subsidy program, however the latest figures for the September quarter show unemployment has risen by 1.3 percentage points to 5.3 per cent. Moreover, net migration, which has been supported by New Zealander’s returning home has started to slow.

The prospect of negative interest rates set by the Reserve Bank of New Zealand are likely to be on the table for next year. Whilst negative interest rates are intended to support both the currency and domestic demand, those settings present a challenge the banking system may have to grapple with over the course of 2021.

Despite these challenges for the next year or so, New Zealand’s medium term prospects remain positive, particularly as a desirable destination for skilled migration and tourism and given New Zealand’s deep comparative advantage in agriculture.

2

Credit growth

Muted credit growth in FY20 and an uncertain outlook.

Overall credit growth was muted in FY20, relying largely on resilient owner occupier housing credit demand, with first home buyers an important support. Investor credit has never been so weak and business credit has fallen for four consecutive months (meaning in net terms that business is paying back more than it is drawing down in new loans).

The credit outlook remains highly uncertain. Consumer and business confidence have improved, but weak labour market conditions, stagnant wage growth and falling net migration could drag on demand for housing credit – the major driver of banking sector revenues.

Net interest margin (NIM)

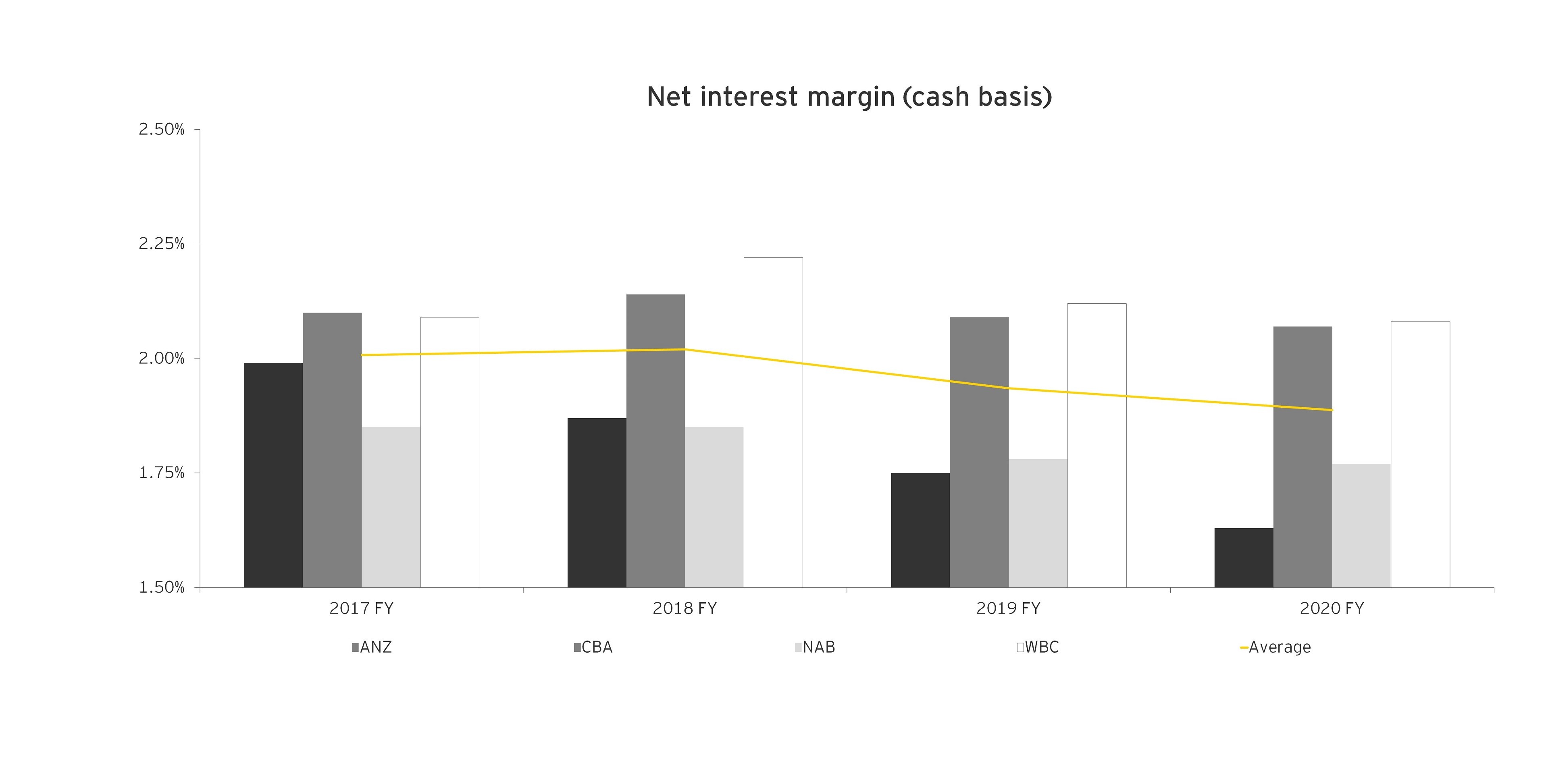

NIM contracted to an average of 1.89 per cent, a decline of 5 bps, largely attributable to the historically low cash rate and aggressive competition. On the upside, strong household and business deposit flows combined with the Reserve Bank’s Term Funding Facility (TFF) have given the banks access to low cost funding. Differential pricing is leading to wider margin spreads for higher risk lending, such as loans with a high loan to value ratio (LVR).

The percentage of funding coming from deposits has increased, with households and businesses shoring up their financial reserves. Deposit growth was particularly strong in the early months of the pandemic as corporate customers drew down on existing credit lines to support working capital. As income support payments taper off, household deposit growth is expected to slow.

The quantitative easing program recently announced by the RBA will place further pressure on margins. While this is good news for borrowers, it may not be good news for net savers and bank shareholders.

Mortgages

So far, housing credit growth has proven more resilient to the economic crisis than expected. Refinancing activity has risen sharply, as borrowers rushed to take advantage of historically low mortgage rates and cash rebate offers. System growth in housing credit was 3.3 per cent over the year to September.[2] This was driven by owner occupier loans, which grew 5.4 per cent, sustained by low interest rates and government incentives, such as the HomeBuilder grant and the First Home Loan Deposit Scheme. Investor lending continued to decline, down 0.4 per cent over the year.

The major banks have been able to use the RBA’s low cost TFF to offer customers attractive fixed-rate home loans, supplemented with cash rebates to win back market share lost after the Financial Services Royal Commission. However, not all the major banks have benefited equally, with strong competition resulting in home loan performance diverging between individual banks.

Concerned that responsible lending obligations might be unduly constraining banks’ lending, the Federal Government has proposed removing most of the obligations currently included in consumer protection legislation. The aim is to eliminate confusion and ambiguity over compliance requirements and reduce verification and inquiry requirements to minimise loan processing delays.

In a move that may also boost lending, the banks are starting to reverse the stricter lending criteria introduced in the early stages of the pandemic for borrowers in industries and areas considered most at risk. This includes easing certain maximum LVR limits but retaining appropriate differential pricing for higher risk loans.

Business

Over the year to September, system growth in business credit was 2.0 per cent,[3] driven mainly by large businesses. There were sharp monthly increases in March and April, as businesses drew down on existing facilities or sought facility increases to boost liquidity.

SME credit growth has remained relatively flat[4] despite Phase 1 of the government’s $40 billion COVID-19 SME lending guarantee scheme, which aimed to provide SMEs with working capital. Phase 1 generated around $2 billion in loans, with two of the major banks accounting for most of the lending. Reports suggest the modest take up under Phase 1 of the scheme may have been due to SMEs wanting greater flexibility in terms, scope and interest rates.

To address these issues, Phase 2, announced in September, incorporates an increased maximum loan size, extended terms, an expanded range of purposes and a cap on interest rates of around 10 per cent. These changes should see more borrowers qualify and apply for funding. The Phase 2 panel of lenders approved to issue the loans, which are 50 per cent backed by a government guarantee, includes the major banks, other ADIs and specialist, non-bank business lenders.[5]

As the Government introduces economic recovery measures to encourage business investment and cash flow for SMEs, some banks have announced increased numbers of business bankers and enhancements to lending services to further support SMEs.

Credit cards

Over the six months to August, personal credit and charge card balances declined sharply, falling by 19 per cent.[6] The decline partly reflects householders paying down debt in the face of the uncertain economic outlook and virtually non-existent overseas travel. However, the use of credit and charge cards was already falling well before the COVID-19 pandemic, possibly reflecting the emerging popularity of non-credit, ‘buy now, pay later’ (BNPL) alternatives. BNPL offerings are particularly attractive to younger customers, who are keen to avoid the interest charges associated with traditional credit card products. In response, some of the major banks have invested in BNPL providers and introduced new ‘no interest’ credit card products to attract a younger cohort.

3

Costs

COVID-19 pandemic response drives up costs but is also an opportunity to accelerate product simplification.

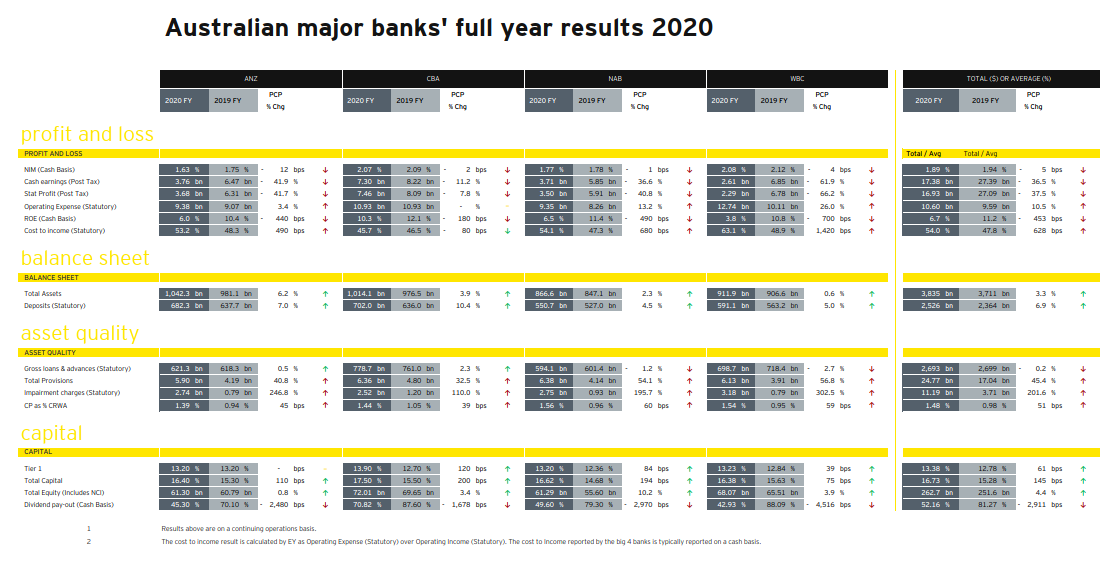

The banks continue to grapple with the twofold challenge of higher costs and lower revenues, as cost to income ratios increased an average of 628 bps in FY20. The banks have managed their underlying operating costs well, with a continued focus on productivity, process optimisation and business simplification initiatives. Despite this, costs remain elevated due to the impact of ongoing remediation programs, enhanced risk and compliance functions and investment in technology programs.

Operating costs have also been driven up by the COVID-19 pandemic, with additional resources and staff needed to support customers, monitor hardship and collections, and reassess customer risk ratings. Some banks have also relocated lower-cost offshored roles back to Australia to improve customer support and overcome pandemic-driven delays in application and approval times. These costs have been partly offset by other cost reduction initiatives.

On the upside, the wealth shackles are lifting for the banks, which should ease associated compliance costs. All have divested, or are in the process of divesting, their mass market wealth businesses to focus on the private banking segment. However, over the short to medium term, the banks will continue to contend with sizeable legacy remediation programs.

Digital

The COVID-19 pandemic has already accelerated the banks’ digital and technology transformation programs. Now, with bank margins under pressure, digital tools can unlock cost savings during the economic uncertainty, in both front and back office operations. The pandemic has changed consumer behaviour, catalysing the use of digital banking products and services. For example, the EY Future Consumer Index found 62 per cent of respondents intending to use less cash in the future and 59 per cent expecting to use more contactless payments. Branch and ATM numbers continued to fall over FY20 as we move closer to a ‘cashless economy’.

The banks have an opportunity to reduce costs by accelerating product simplification. Using their increased interaction with customers, they can move customers off legacy products to simpler, more cost-effective digital offerings. Banks are also focused on internal digital enablement. They are digitising traditional manual processes to match growing demand, which, in turn, reduces costs. Intelligent automation and advanced analytics not only create efficiencies, they also offer banks much-needed scalability to optimise processes. What cannot be automated should be re-engineered and digitised.

Remote working

Remote working policies provide an opportunity for banks to reimagine how a distributed workforce could operate in the long term. Given the opportunity to reduce real estate footprints, the potential cost saving implications could be profound.

4

Asset quality

NPLs still low but deterioration expected as support measures unwind.

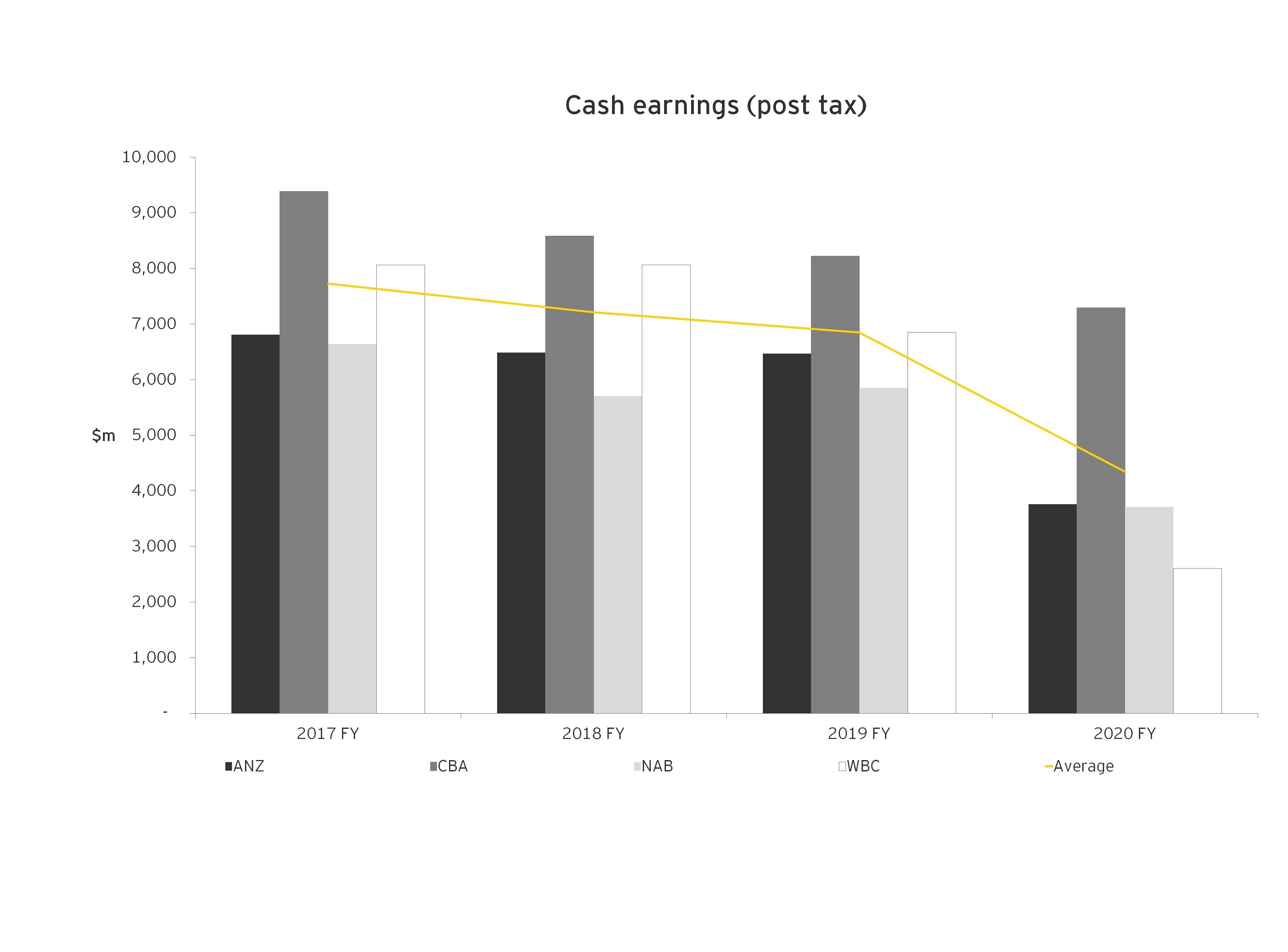

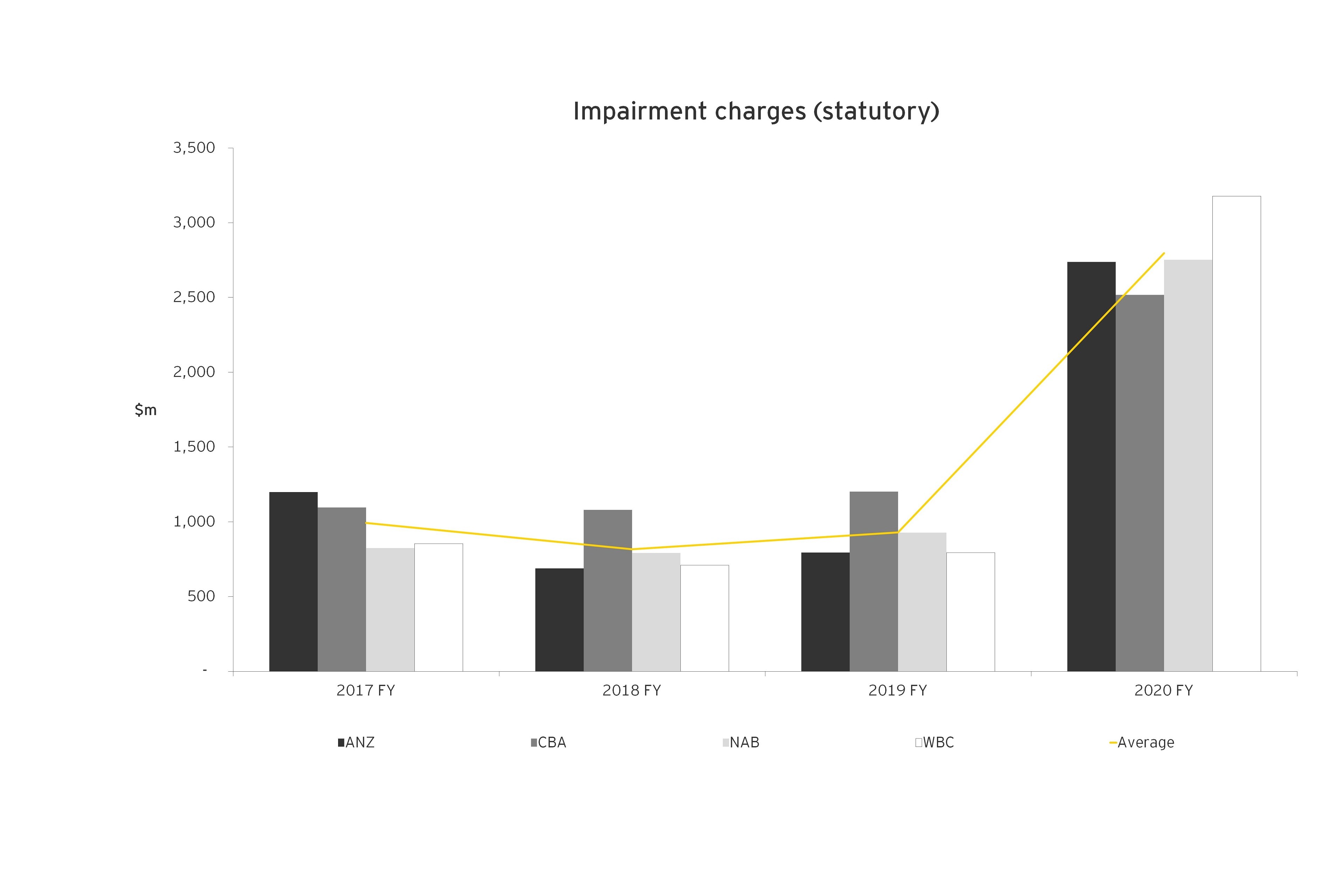

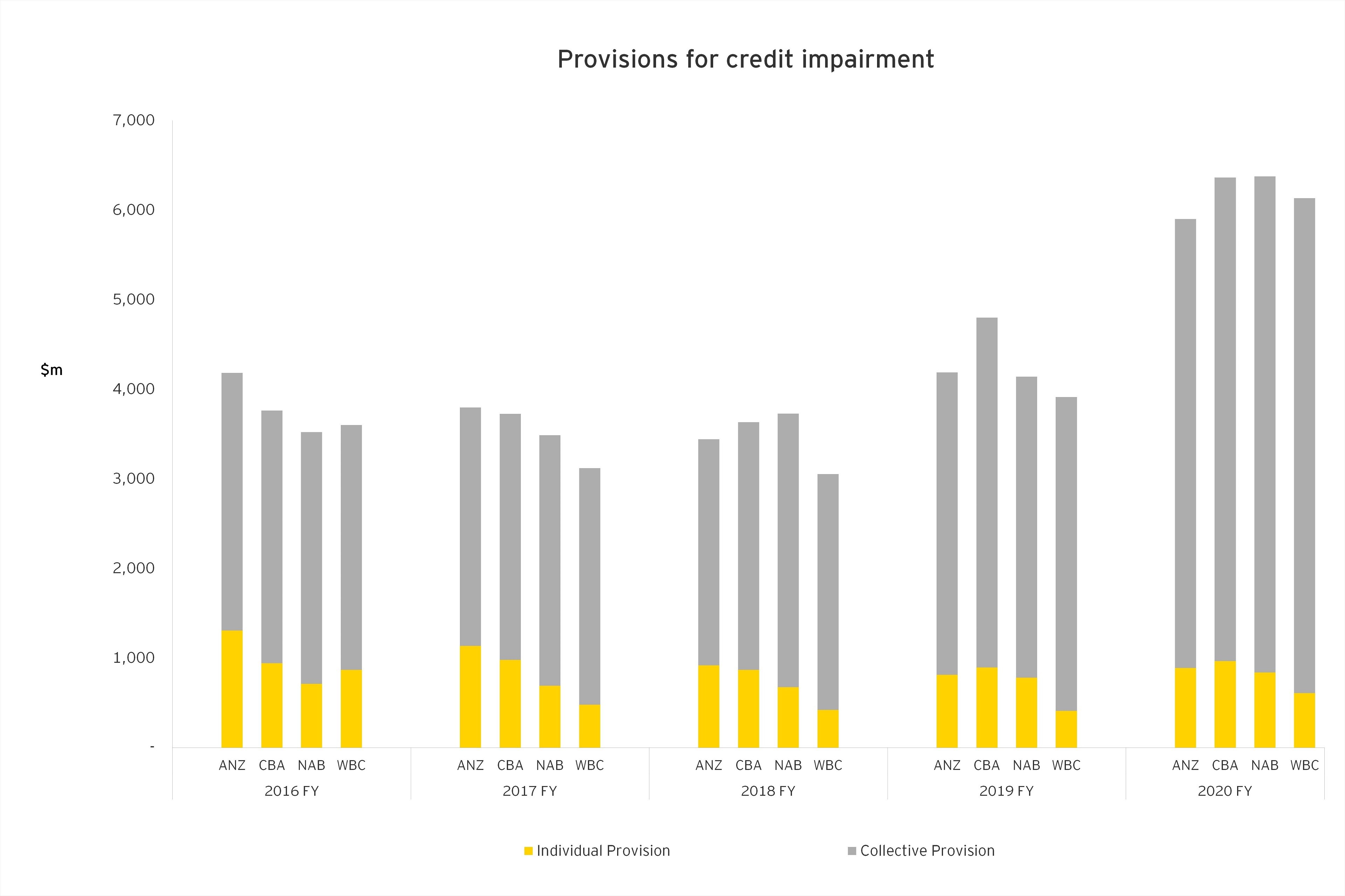

This year, impairment charges totalled $11.19 billion, while total provisions booked on the balance sheet have topped $24.77 billion. The uncertain economic outlook and how to factor in the impact of the high levels of government support continue to challenge the banks’ decisions on provisions. Executives are making greater use of management judgement, assisted by a variety of modelling approaches, including new scenarios, the use of stress testing results and additional management overlays.

The full impact of the economic downturn on asset quality remains impossible to estimate. Loan repayment deferrals, government income support and the temporary easing of loan loss recognition requirements are obscuring the full extent of asset quality deterioration. Realised losses and nonperforming loans (NPLs) have remained low, thanks largely to government and regulatory support measures. However, banks are anticipating higher loan losses and defaults as relief measures are unwound and unemployment rises to its expected peak around June 2021.

Business insolvencies are running at a much lower rate than usual, supported by the temporary insolvency relief measures introduced at the onset of the pandemic. This is prompting concern over a possible jump in failed businesses once support measures are removed. Among the high risk industries are accommodation and food services, arts and recreation services and retail trade.

Deferrals

The percentage of loans subject to repayment deferral across the sector has been steadily declining, from a peak of around 10 per cent in June to 6.7 per cent in September.[7] As at 30 September, $179 billion of loans were subject to payment deferral, representing 7.4 per cent of housing loans and 10.8 per cent of SME loans. September marked the third month in a row where more customers exited than applied for a deferral. While repayments have resumed on many of the exited deferrals, the banks remain concerned about the elevated risk posed by high LVR, interest-only and investor housing loans. As at September, 10 per cent of loans subject to repayment deferral had an LVR greater than 90 per cent, 14 per cent were interest-only loans and 35 per cent were investor loans.

The banks have been contacting affected customers to encourage them to restart repayments or restructure loans. This has prompted a reminder from the Reserve Bank that appropriate culture will be especially important as banks face the challenging task of dealing with customers' loan repayment deferrals while responding more broadly to the economic contraction.[8]

Collections

The expected increase in customers entering financial difficulty will create a significant collections challenge for the banking sector. With the benign conditions of the past three decades, existing collections processes have tended to be under-invested. As a result, many banks’ collections systems are relying on incomplete data, manual processes and legacy technology. This means banks may struggle to identify customer segments most at risk.

The large numbers of customers likely to need customised payment strategies and solutions is forcing banks to rethink their collections model. The major banks are investing heavily to scale their capabilities. As they do so, they must find the balance between customer, business, shareholder, regulatory and community outcomes, ensuring they treat customers fairly.

The key is to transform the collections model from a labour-intensive outbound approach focused on finding customers who are able to pay, to a loss-preventative, inbound operation where banks offer pre-approved treatment strategies and personalised communications. In this way, banks can incentivise consumers to proactively reach out to them, delivering more personalised, effective customer service, at scale – while sustaining loyalty.

To make this work, banks will need a more nuanced approach to measuring and monitoring credit risk. Predictive and high-frequency analytics will be essential to segment customers and deeply understand each customer’s situation and their probability of default. By analysing all the available customer data (including from non-traditional data sources, such as social media), banks can build more robust customer hardship profiles and define proactive, targeted response strategies. Banks that replace a ‘transactions’ approach with a ‘customer solutions’ approach to collections will not only create a better, more personalised experience for vulnerable customers – differentiating themselves in the market – but also improve recovery returns.

5

Capital

Still ‘unquestionably strong’.

The banks remain well capitalised, bolstered by APRA’s temporary modification of loan loss recognition requirements and higher rates of retained earnings. This has seen the average CET1 ratio for the banks remain stable at 11.4 per cent – above the 10.5 per cent ‘unquestionably strong’ CET1 benchmark – despite the large increase in provisions. However, capital levels are probably not as high as stated, given as yet unrecognised impaired assets.

In contrast to 1H20, which saw the three major banks with 31 March half-year ends reduce or defer dividends, all the banks have declared dividends for 2H20. However, dividends were reduced, in line with APRA guidance to retain 50 per cent of earnings to ensure continued capacity to fund loan growth and absorb potential losses.

Payout ratios have also declined substantially. The lower earnings of recent periods have already put pressure on capital generation and the banks’ ability to sustain elevated payout ratios. With the current uncertain outlook, payout ratios are likely to remain constrained over the short to medium term. This is likely to weigh on the banks’ share prices, which have not yet recovered from their steep falls following the onset of the pandemic. Share prices remain around 22 per cent lower than the start of the year for most of the banks.

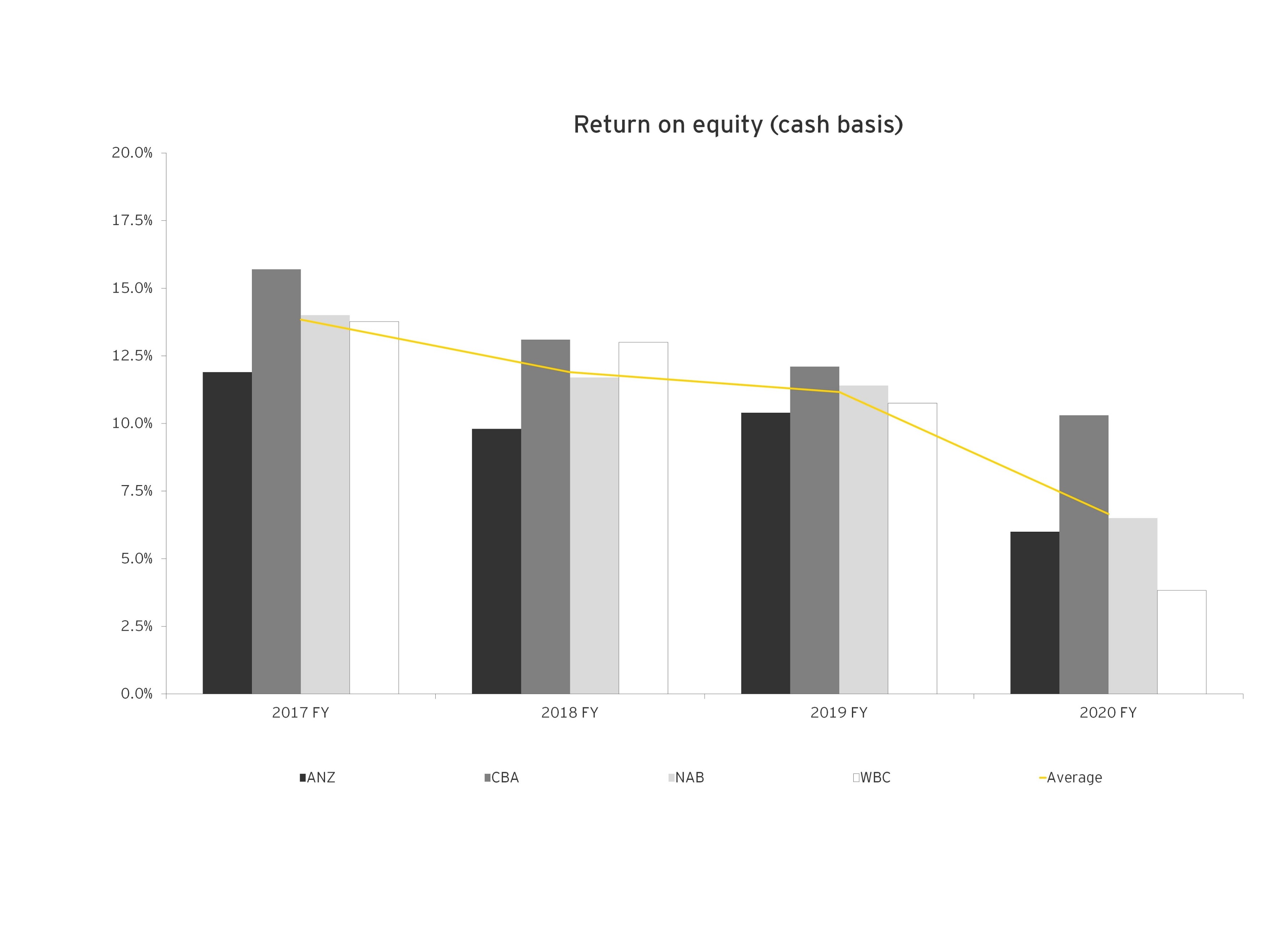

Return on equity has declined further, driven largely by the impact of impairment charges on profits. Restoring ROE to its previous double-digit levels will prove difficult in the prevailing low-growth environment.

6

What next?

A focus on rebuilding profitability.

The banks remain resilient but risks are elevated. The challenging operating environment brought about by the pandemic – including the economic downturn, dampened credit demand and significant asset quality risks – will weigh on the banks’ future revenues, profits and returns.

However, as we transition into the recovery phase, banks can still position for future growth. To rebuild profitability in the wake of the COVID-19 crisis, we expect to see banks focused on improving efficiencies and developing the customer experience. Strategies will include:

- Reshaping the cost base through cost transformation and fast tracking digital transformation strategies

- Optimising branch footprints

- Implementing a more flexible operating model with a dispersed workforce

- Introducing new digital products and services to address changing customer behaviours and needs, underpinned by an enhanced data analytics capability

With improved digital capabilities and more agile operating models, banks will be able to deliver a better customer experience and create capacity to further invest in transformation.

Summary

Earnings down as banks prepare for the full economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.