EY refers to the global organisation, and may refer to one or more, of the member firms of Ernst & Young Global Limited, each of which is a separate legal entity. Ernst & Young Global Limited, a UK company limited by guarantee, does not provide services to clients.

How EY can help

-

The EY Net Zero Centre brings together EY’s intellectual property, strategic insight, expertise and deep knowledge in energy and climate change leadership to solve the big problems ahead as we move towards net zero emissions by 2050.

Read more

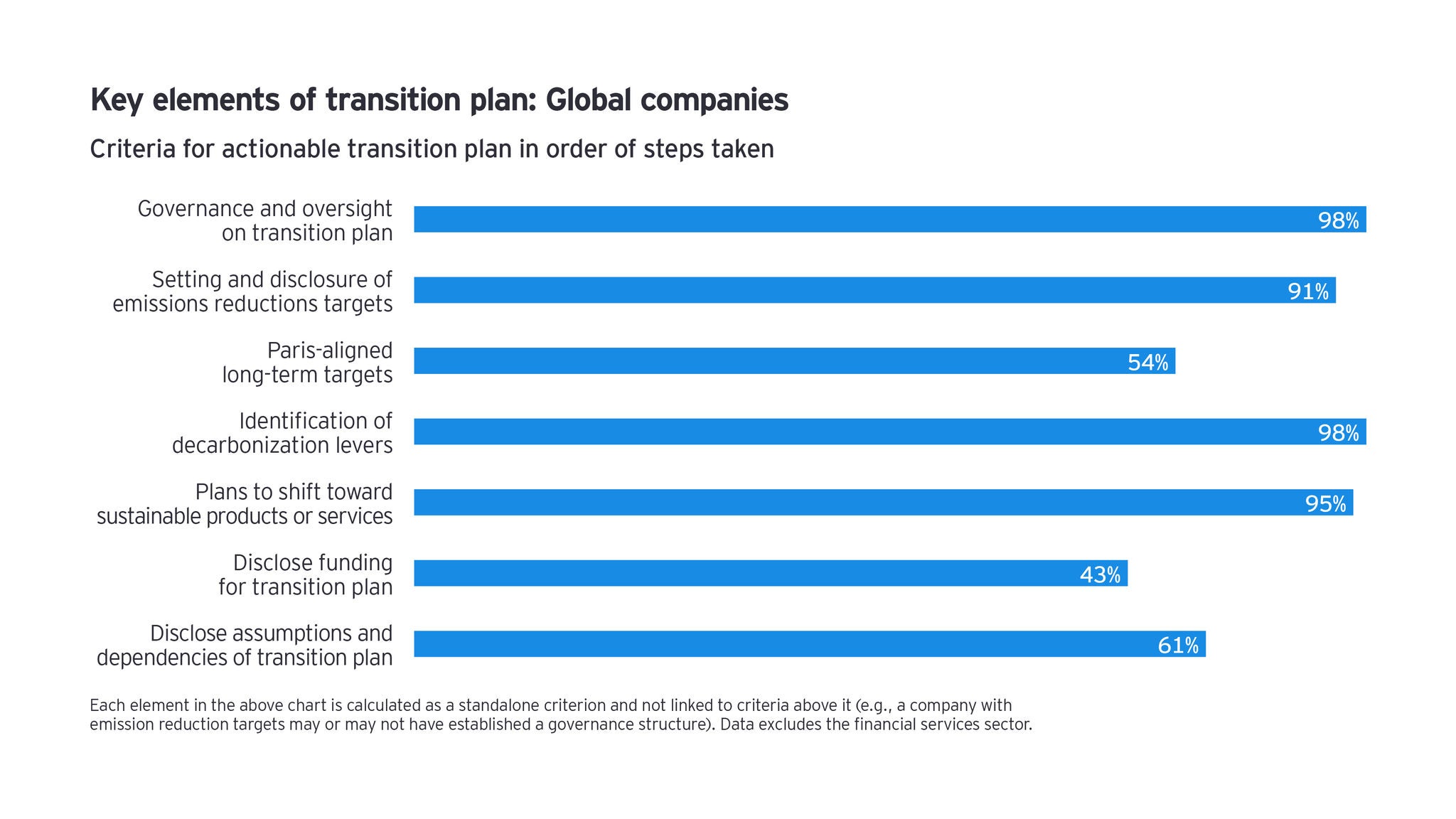

While around two-thirds of companies claim to have a transition plan, many show little or no progress against their earlier commitments, and some are moving backwards. Regulatory and political uncertainty, the cost and effort required to produce a transition plan, and reassessment of previous bold commitments all contribute to this stagnation.

When we apply a more rigorous test – looking for plans that are actionable, costed, governed and tied to milestones – only 22% of global companies within our sample meet this higher threshold. In Australia, just 13% do. In New Zealand, none do. It is a striking mismatch: ambition widely declared, substance narrowly delivered.

Some organisations have published strategies without building the machinery to implement them. Others are revisiting early commitments in light of rising costs, volatile policy signals or a clearer understanding of what genuine decarbonisation entails.

For investors, regulators and communities, this matters. Transition plans will influence capital flows, insurance exposure, audit scrutiny and the credibility of forward earnings. In other words: the difference between a claimed plan and a credible one is financial.