Chapter 1

The right structure creates a solid foundation

Approaches utilising existing frameworks are easier to employ and have a higher chance of success.

Where a firm has operations in different countries, generally the rules of the most stringent jurisdiction are incorporated as part of a global approach (particularly given the similarities between most regulations), with jurisdiction-specific elements covered locally.

Operational resilience is part of the first line of defence (1LoD) from a controls perspective and should be owned by the business. A central operational resilience team is also part of the 1LoD, as they typically will have responsibility to implement the approach even if they are not responsible for maintaining standards and consistency. Challenge should be provided within the second line of defence (2LoD) by non-financial risk.

Senior manager function (SMF24s)

The UK regulation is quite clear that the chief operating officer (COO) or chief information officer (CIO) (SMF24) is accountable for the operational resilience approach, including the firm’s policy, standards and operating model. It is also clear that the executives who own the important business services (IBS), and typically those revenues, are responsible for the resilience of their services, addressing any vulnerabilities identified that could lead to breaches of impact tolerance. The challenge that firms face is how to make ownership by the business owner effective whilst ensuring that the firmwide approach is adopted and demonstrates that the appropriate level of resources to carry out activities is maintained.

Business service owner

Generally, individual business owners have embraced the new approach to operational resilience. Some have taken a close interest in the end-to-end delivery of their services; others realise their obligations under regulations, such as the UK Senior Managers’ Regime². Where this is not the case, adding resilience into executive scorecards can be effective; also obtaining formal sign off on their service’s resilience from the owner can work. Whilst the UK regulatory approach is clear, it is difficult to imagine that other regulators are comfortable with those who own businesses not being familiar with how their services are delivered and their resilience capabilities.

Central team vs business functions

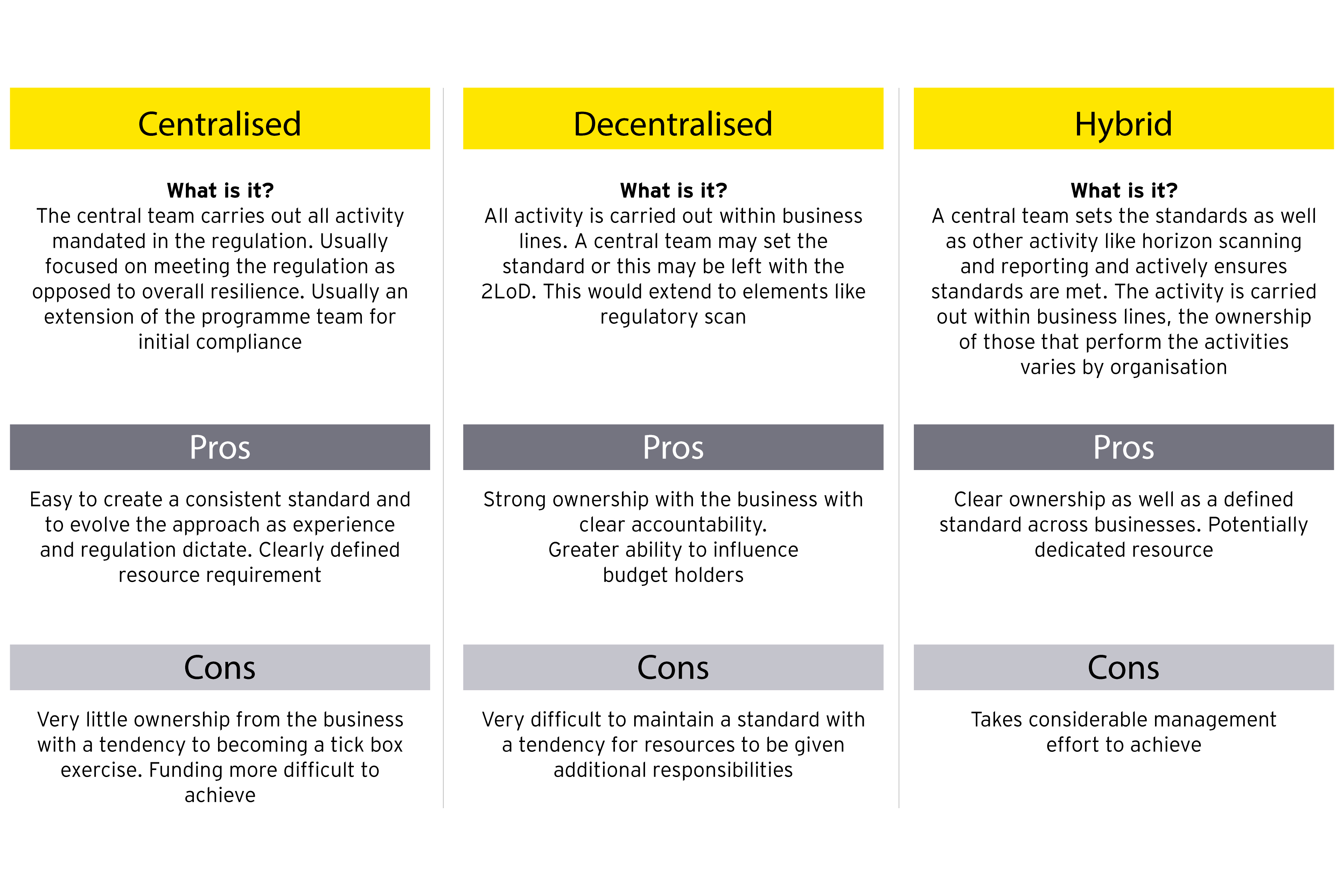

Central teams are typically responsible for the maintenance of the approach, standardisation and monitoring of activity, as well as owning the repositories of information around an IBS, impact tolerances, scenarios applied, results and self-assessments. The business function within firms is often responsible for carrying out regular IBS assessments and, critically, addressing identified vulnerabilities. The exact split between the business and the central team will vary between firms depending on how they are structured. We have broadly seen three variations that firms are adopting for their approach to operational resilience.

Three approaches to organisational structures

Chapter 2

Governance and metrics play a crucial role

The governance chain relies on identifying issues, vulnerabilities and setting impact tolerances.

Effective, efficient and demonstrable governance at the appropriate level is key to balancing the trade-off between resilience and the cost of enhancements, as well as maintaining activities and controls. The primary path to review and escalate the resilience of an IBS should be the executive chain of committees (from business to division to group executive committee) to demonstrate the importance, as well as being the primary route for matching resources and funding the resilience priorities.

The non-executive risk chain or committees (that feed into the board risk committee) should review resilience as part of the non-financial risk (NFR) exposure that firms face. Under the regulation, however, there should not be a risk appetite for resilience for IBS. This should replicate at all levels up to and including the board risk committee.

Programme governance around the functioning of the operational resilience approach can be included in one of the other governance pathways depending on firm structure, particularly the nature of the SMF24 role. This should cover the programme as a whole, with a focus on the performance of operational resilience lifecycle activities.

The key to effective governance is relevant, timely and reliable information. Metrics around operational resilience generally fall into three categories:

- Programme metrics. Complete the mandated steps, such as scenario testing or annual reviews for each IBS on time.

- Vulnerability tracking and resolution. This is the primary driver for improving the firm’s resilience and the primary indicator for the level of resilience within the firm. This can include inherent vulnerabilities due to process design or transitory issues, such as staff shortages.

- Resilience over time. Keeping the IBS within impact tolerance, and tracking whether it fell outside impact tolerance over the last 12 months, and if there were there any near misses (of it falling outside of impact tolerance). For the UK, it is essential to be able to notify the regulators of an impact tolerance breach.

Chapter 3

Integration: The key to improving resilience efficiently

A service level view and integrating with existing activities will enable an effective approach.

Integrating with existing frameworks

1. Business continuity

Of all existing activity, business continuity management (BCM) is the one that is most closely related to operational resilience. At most firms, BCM historically has been a bottom-up exercise whilst operational resilience is very much top down. This mismatch has understandably caused challenges to what are otherwise similar activities.

The key is aligning prioritisation between the elements that support IBS and the BCM system of record. One key difference is that typically, BCM focuses on a limited range of scenarios, physical and recoverable within recovery time objectives (RTO), rather than the more extensive, severe but plausible, list of potential events. This impacts the re-usability of testing results and firms look to increase the scope of BCM testing to cover the full range of scenarios. This is more straightforward than it appears since generally the range of recovery actions being tested will be more limited than the number of potential scenarios to consider.

2. Non-financial risk (NFR)

While operational resilience and NFR have much in common, the different location (1LoD vs. 2LoD) and the focus on recovery as opposed to prevention makes the distinction. The key input that NFR provides for operational resilience is horizon scanning for disruptive risks and events and creating the subset of the material risk inventory that covers these. This becomes the benchmark for the vulnerability assessment, creating severe but plausible scenarios for testing and lessons learned reviews of events happening to other organisations. We would anticipate that operational resilience will appear within risk control self-assessments (RCSAs), both for businesses and the central team generating challenge from NFR.

3. Third-party risk management

There is significant overlap driven by the need to ensure that material third parties can continue to deliver the contracted services if disrupted. This is evident given how closely linked the regulation around third parties and operational resilience are, such as the EU’s digital operational resilience act (DORA)³ and the Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA) supervisory statement (SS2/21)⁴. The key resilience considerations for vendors are around resilience capability, control and concentration and apply equally to internal and external third parties. Prioritisation should be reviewed to ensure that it is aligned, along with a regular vendor questionnaire. Depending on the level of outsourcing, consideration should be given to integrating third parties into testing to provide a higher degree of confidence in recovery actions.

One area of importance is the level of information provided by vendors on how they deliver their services and resilience capabilities; both at the contract stage and on an ongoing basis. The PRA Critical Suppliers Discussion paper (DP3/22)⁵ and the EU DORA point to greater disclosure going forward, but this will take time with firms struggling to get the necessary information in the short-term.

Thought also needs to be given to the impact of planned changes of critical suppliers to ensure that resilience is not impacted.

4. New business and IT change

Change management (or lack of) is the single biggest cause of IT disruption according to an FCA report⁶, titled ‘Cyber and Technology Resilience: Themes from cross-sector survey 2017-18’. New business and changes to the way that services are delivered should be captured and trigger a review of their impact on the resilience profile of the firm where relevant. Thought needs to be given to how activity is triggered, as well as filtering to ensure that the activity that is reviewed has an impact on resilience without being overwhelmed by the volume of changes. Firms should consider how the governance of strategic change occurs and seek to embed resilience considerations into this lifecycle.

5. Cybersecurity and IT disaster recovery (ITDR)

Typically, cybersecurity and ITDR fall outside BCM, often having limited interaction. Given their critical impact on almost every financial service provided, they need to be incorporated into the mapping, vulnerability assessment and testing phases. The elements of delivery processes for IBS need to be correctly prioritised in recovery plans. To do this, they also need to be tagged correctly in technology registers, such as the firm’s configuration management database (CMDB). This will allow enhanced testing both in terms of scope, nature of test and frequency.

6. Recovery and resolution planning (RRP)

With regulators mandating firms’ plans to recover from financial distress and also be able to wind down in a controlled fashion by focussing on critical operations, there is a certain degree of overlap between operational resilience and resolution element of RRP. The key difference is the longer time horizon of RRP, coupled with the nature of client harm that is covered in the UK operational resilience regulation. The principal area to align is around the granularity, mapping and taxonomy of services and indications on the list of critical operations as to which ones are IBS. The principal benefit lies in potentially coordinating the testing for maximum efficiency and to avoid duplication.

Chapter 4

Enterprise resilience: Taking the holistic view

Integrating activities across the firm can lead to improved resilience delivered efficiently.

We have seen firms plan to combine their existing BCM with their nascent operational resilience capabilities to improve efficiency and create a consistent rationale.

The enabler for this is a unified prioritisation of internal and external services at a common level of granularity. To create an integrated approach, firms need to fit their IBS into existing prioritisation in a logical way that recognises critical infrastructure (such as active directory), key internal services (such as liquidity and risk management) as well as other services to create a continuum.

The activities and the level of protection for each prioritisation category is then the next level to define. This should balance the harm the unavailability of the service would cause against, primarily, the length of time to recover the service.

When looking at the lifecycle, the top-down nature of operational resilience lends itself to be a better starting point for an integrated lifecycle. Operational resilience is a journey with no defined outcome. The regulators’ expectation is that firms’ resilience improves over time so what was sufficient for the initial deadline will not be going forward. Firms can address this by putting in place the right structure, people and, particularly, metrics and governance that drive a self-correcting approach.

Related articles

Summary

In this first in a series of articles, we explore operational resilience and outline considerations for financial service leaders as they take measures to meet the regulators’ intent. As it is crucial to take action well before the 2025 implementation deadline, we have gathered insights and practical steps for operational resilience leads to consider.