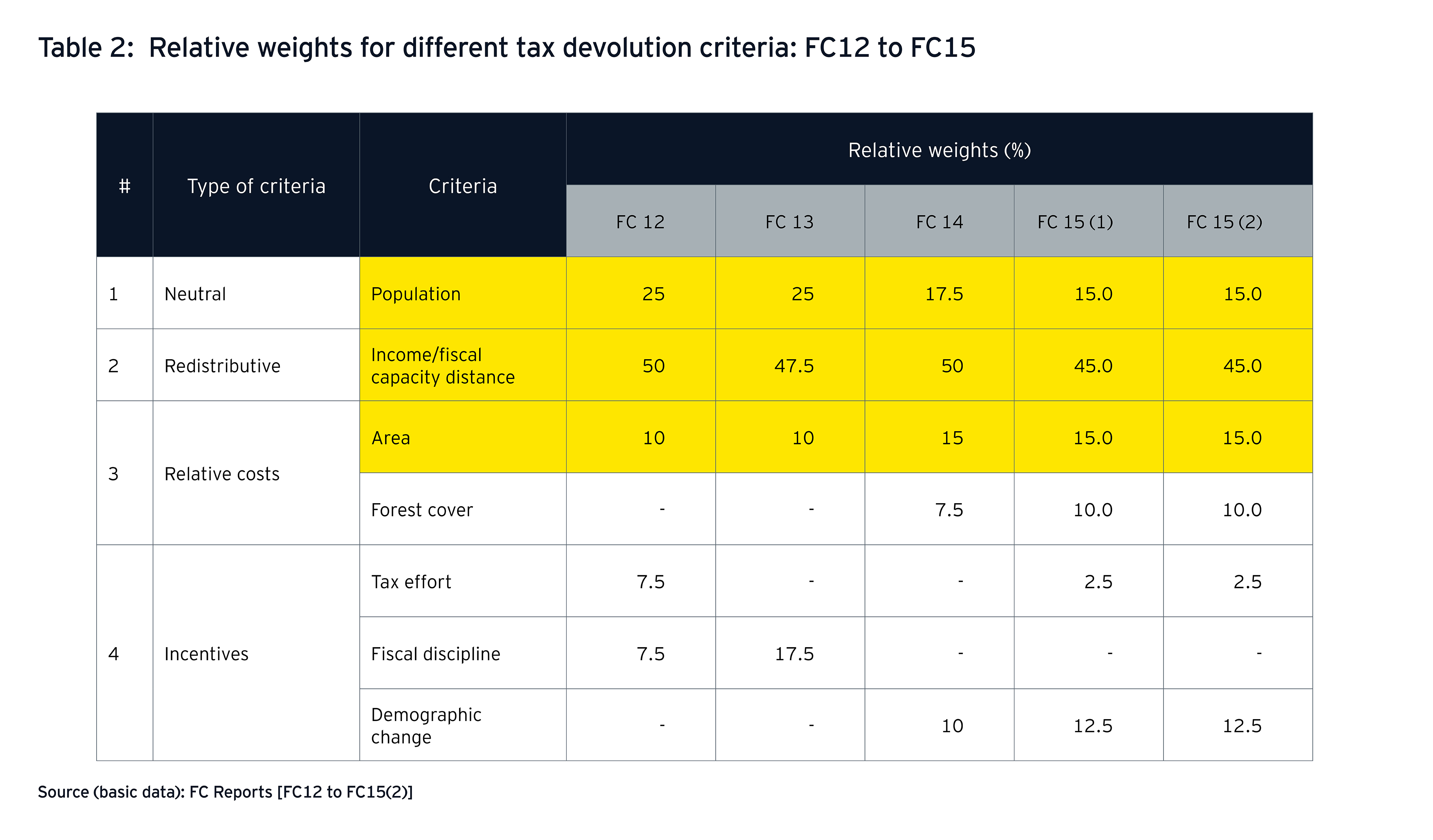

There has been a debate regarding the relative emphasis that needs to be given to criteria reflecting equity vis-à-vis those reflecting efficiency. While some of the less developed states argue in favor of assigning a relatively higher weight to equity considerations, some of the high per capita income states argue for higher weights to efficiency considerations.

In the literature on fiscal federalism as well as in empirical practice, in many established federal countries, the principle of equalization in fiscal transfers has been considered desirable on account of its compatibility with equity as well as efficiency. Empirically, two approaches have evolved in regard to translating equalization into practice. In the first approach, equalization is limited to fiscal capacity equalization1. In the second approach, this is supplemented by expenditure-side equalization. Canada follows the first approach, while Australia is an example of the second.

Restoring fiscal balance

In 2018, the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management Act was amended based on the report from the FRBM Review Committee. There were four key changes brought about by this amendment. First, the target of maintaining a balance or surplus on the revenue account was given up. Second, the fiscal deficit to GDP targets for both central and state governments were kept at 3% each and these were made operational targets. Third, the statutory target was defined in terms of government debt-GDP ratios. Separate limits were defined for the central government at 40% of GDP and 20% for the aggregate of states. Fourth, several countercyclical clauses were provided as part of the Act. In the literature that developed subsequently, certain inconsistencies in the debt and fiscal deficit targets were noted2. Also, the levels of government debt and fiscal deficits rose inordinately in FY21 in response to COVID-19. There is a need for the GoI to re-examine the FRBMA. FC15 had also recommended the setting up of a High-Powered Intergovernmental Group to examine these issues. In particular, three issues need to be addressed. First, the debt and fiscal deficit targets should be made internally consistent. Second, once the new norms are specified, a new glide path can be indicated by the Commission based on its growth projections. Third, the FRBMA needs a more realistic macro stabilization clause to handle the economic slowdowns like the one faced during FY20 and FY21.

In recent years, there has also been a re-emphasis on provision of non-merit subsidies by some of the state governments. An example of this is the provision of free electricity, which is a private good with limited externalities. Another issue that appears to be gathering momentum pertains to the re-introduction of the old pension scheme in some states without a clear identification of sources of financing the resultant fiscal burdens. FC16 should re-examine these issues given their impact on the fiscal imbalances of central and state governments. The Commission should find methods to penalize states who are not able to keep their fiscal deficit within the FRL norms. One possibility is to set up a ‘Loan Council’, which was recommended by FC12, to oversee the debt and fiscal deficit profiles of the central and state governments. This council may consist of the Chairperson and members representing the Ministry of Finance, Reserve Bank of India, two state governments by rotation, and fiscal experts.