EY refers to the global organization, and may refer to one or more, of the member firms of Ernst & Young Global Limited, each of which is a separate legal entity. Ernst & Young Global Limited, a UK company limited by guarantee, does not provide services to clients.

Download the latest issue

Government should specify its fiscal consolidation strategy in the FY25 Budget with a view to meeting the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management (FRBM) targets.

In brief

- The IMF has raised the possibility of India’s combined government debt levels crossing 100% of GDP under a stress scenario.

- The FY25 Interim Budget would provide an occasion to give a clear roadmap of achieving the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management Act, 2003 (FRBMA) targets.

- A reduction in GoI’s fiscal deficit in FY25 may call for some downward adjustment in capital expenditure growth.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF), in its 2023 Article IV Consultation, has suggested that an ambitious fiscal consolidation path is needed to replenish buffers and sustainably lower debt, while supporting inclusive growth. Given the shocks that India has experienced historically, and instances of fiscal slippages between 2000 and 2020, the baseline carries the risk that, should similar shocks materialize, debt would exceed 100% of GDP in the medium term. IMF’s stress scenario envisages India’s real GDP growth to be 1.5% points below their estimated potential growth at 6.3%. This implies an actual real GDP growth of 4.8%. This can potentially materialize if India experiences another major economic shock due to global factors. Even at this lower growth rate, the risk of combined government debt to GDP ratio crossing 100% is relatively low. The Government of India (GoI) would do well to highlight India’s debt and fiscal deficit situation and the glide path for incrementally reducing these to reach the targets as per the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management (FRBM) Act in the forthcoming FY25 Interim Budget.

India’s government debt levels: Adjustment after reaching the COVID year’s peak

The profile of the government debt-GDP ratio indicates that the state governments have shown an aggregate debt-GDP ratio of about 30% which can be considered sustainable under certain macro assumptions. If the states are to be given a debt-GDP target of 30%, the central government will have to reduce its own target to 30% of GDP in order to remain consistent with the consolidated target of 60%. However, the central government has exceeded even the FRBM debt-GDP target of 40% for many years (Chart 1).

The extent of borrowing by the Government of India (GoI) depends on:

- GoI’s revenue receipts prior to fiscal transfers to states in the form of tax devolution and grants.

- The magnitude of fiscal transfers to states determined by the Finance Commission (FC) and to some extent by the central government itself.

- The competition between GoI and states for fiscal space as reflected by their respective shares in combined primary expenditure1.

- GoI’s key role in macro stabilization in the face of exogenous economic shocks.

GoI’s committed expenditures (pensions, interest payments, and fiscal transfers) have increased relative to its gross revenue receipts, averaging 84.5% during FY19 to FY23. On the revenue side, the share of GoI (post transfers) in the combined revenue receipts has fallen. This is due to a fall in its share in combined tax revenues, which is primarily attributable to an increase in tax devolution to states as determined by successive FCs. The GoI competes with the state governments for fiscal space, which can be indicated by its share in the combined primary expenditure1. While this share has fallen in recent years, it remains above the GoI’s share in the combined revenue receipts. This has been possible only by higher reliance on borrowing. The share of the GoI in the combined fiscal deficit has increased to 71% in FY22. This implies a higher share of GoI in combined debt as well as interest payments. Under these circumstances, the GoI may not stick to the fiscal deficit of 3% of GDP as per the 2018 FRBMA target. Instead, it may like to settle at a higher fiscal deficit relative to GDP along with a debt-GDP ratio of 40%. In such a case, the target for the combined government debt level will have to be increased to above 60% of GDP.

FY25 Interim Budget arithmetic

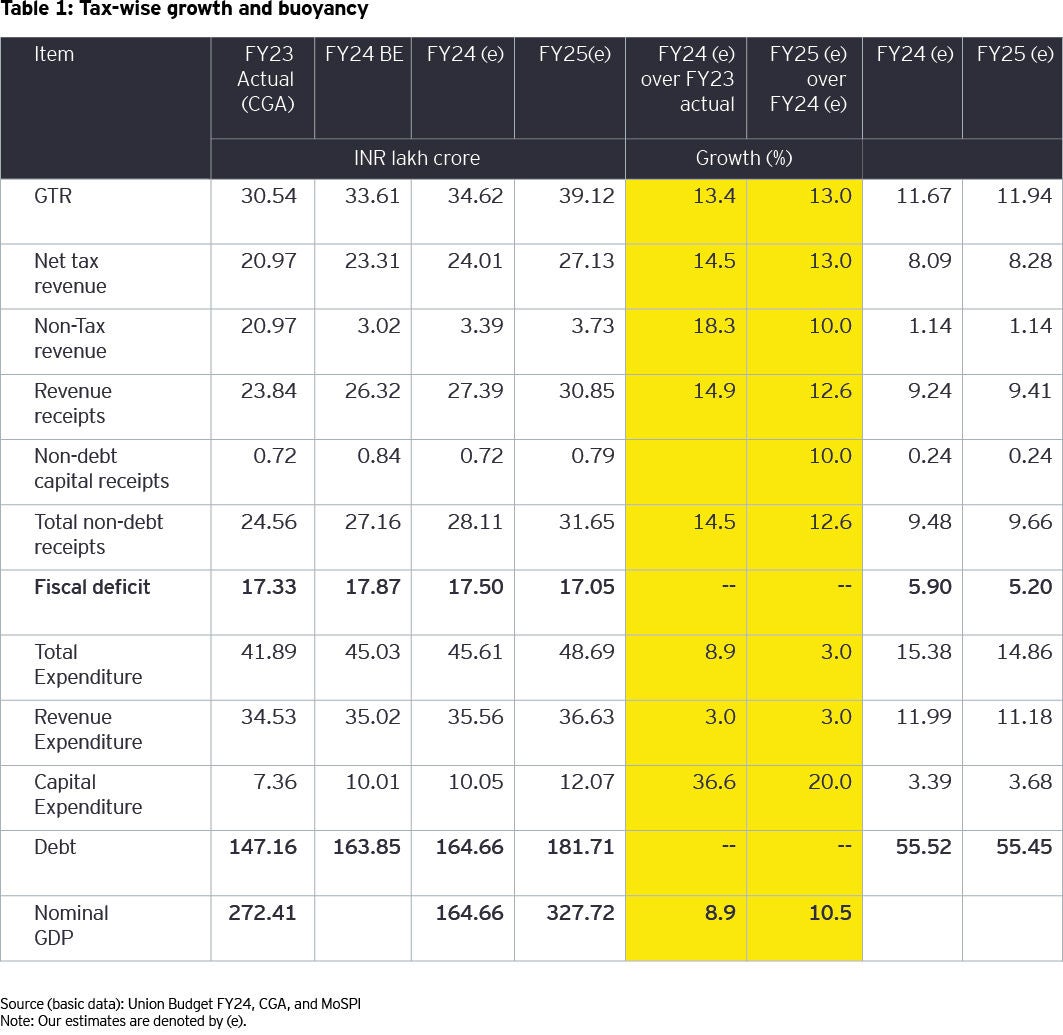

Table 1 shows that a near 13% growth in GoI’s gross tax revenues (GTR) over FY23 actuals would be the main factor that would take GoI’s fiscal deficit close to the budgeted level of 5.9% of GDP in FY24 provided total expenditure growth remains limited to just about 9% decomposed into revenue and capital expenditure growth rates of 3% and 37% respectively. If these numbers turn out to be close to the revised estimates for FY24, we can work out the indicative magnitudes of Budget Estimates (BE) for FY25. The target of reducing fiscal deficit from 5.9% to 5.2% of GDP may call for reducing capital expenditure growth to 20% provided a GTR growth of close to 13% is maintained with an underlying assumption of nominal GDP growth at 10.5%. This implies a GTR buoyancy of 1.24. However, maintaining a high growth in government capital expenditure is critical for sustaining real GDP growth at around 7%. Maintaining a GTR buoyancy of 1.25, a combination of nominal GDP growth of 11.5% and marginal adjustment in the fiscal deficit target to say, 5.3% of GDP in FY25, may accommodate a higher capital expenditure growth of close to 30%. Such a combination appears to be within the feasibility range.

It is estimated that by sustaining a nominal GDP growth at 10.5% and reducing the fiscal deficit to GDP ratio to 3% by FY29, it would take up to 13 years for the GoI to reach its FRBMA debt GDP target of 40%2. However, if fiscal deficit is retained at 4% of GDP FY27 onwards, achieving this debt target would not be possible. There are many possibilities of slippage. For example, if there is a shock, slowing down the growth in say about five years, reaching the debt target may take up to FY43. The GoI should specify, in the FY25 Interim Budget, the assumptions regarding the trajectories of fiscal deficit and the nominal growth to indicate a realistic path to achieve the FRBMA targets.

Download the latest issue

Summary

Reducing GoI’s fiscal imbalances in FY25 requires a downward adjustment in its capital expenditure growth. The magnitude of adjustment would become progressively larger as fiscal deficit is reduced closer to 3% of GDP. Given that GoI’s capital expenditure has served as the key growth driver, a realistic combination of a reduction in fiscal deficit and capital expenditure growth will also have to be worked out in GoI’s FY25 Budget.

How EY can help