How do these China tariffs differ from the 2018 trade conflict?

The 2018 tariffs on China largely targeted intermediate goods — industrial inputs used in US manufacturing — minimizing direct inflationary impacts on consumers. In contrast, the 2025 tariffs focus more heavily on finished consumer goods, including electronics, apparel and household products, making higher retail prices for American households more likely.

The end of the de minimis exemption — which previously allowed low-value shipments to enter the US tariff-free — further amplifies the impact, reducing avenues for cost avoidance for consumers and increasing compliance burdens for retailers.

What mechanism was used to impose the tariffs?

Trump invoked the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA), the National Emergencies Act, and Sections 301 and 604 of the Trade Act of 1974.

The IEEPA in particular gives the president the authority to regulate commerce after declaring a national emergency if they believe there is an “unusual and extraordinary threat” to the US’ national security, foreign policy or economy.

President Richard Nixon levied a 10% across-the-board tariff on imports in August 1971 to force other countries to revalue their currencies against the dollar — using the Trading with the Enemy Act of 1917. But no prior president has used the IEEPA to impose tariffs on trading partners. Trump threatened to use the IEEPA to impose tariffs on Mexico during his first term, but he did not follow through as Mexico agreed to reinforce border security.

Why would Canadian energy exports have been subject to a reduced 10% tariff?

With no readily available short-term alternatives for Canadian oil and gas, imposing steep tariffs would be economically counterproductive. By opting for a 10% tariff rather than 25%, the administration is likely aiming to balance its stated policy with inflation concerns — ensuring a trade barrier is in place while mitigating the risk of domestic price surges.

Is retaliation in a trade conflict optimal? And is it likely?

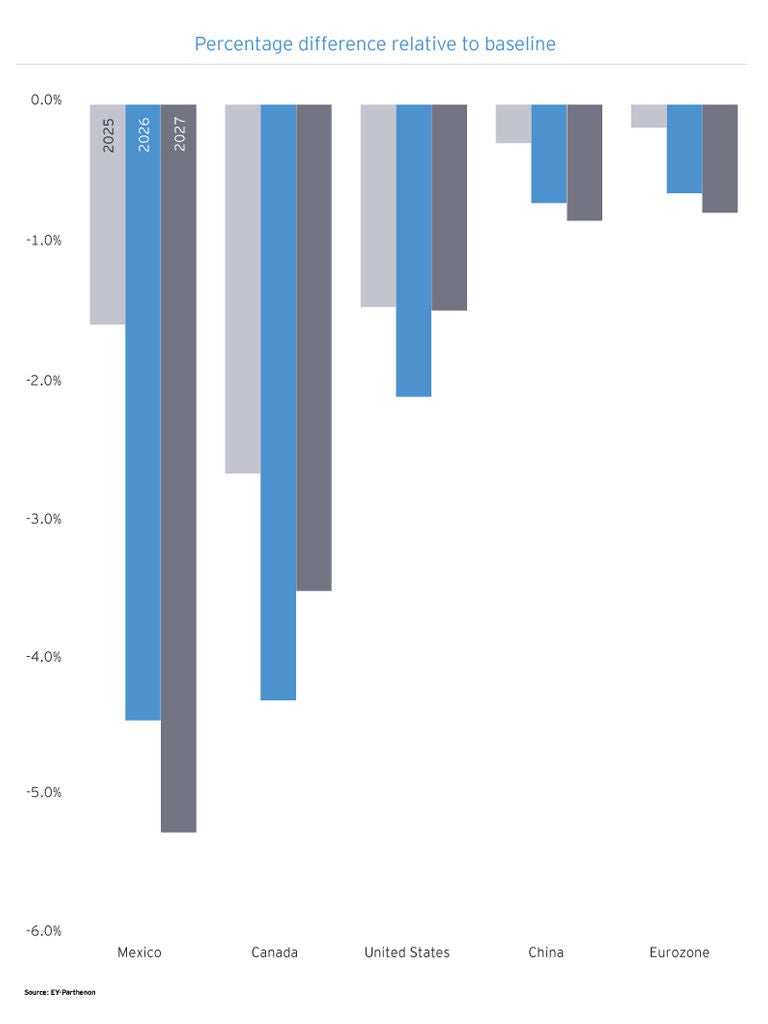

Trade retaliation is a complex paradox. While economic theory suggests that refraining from countermeasures is often the best approach — since retaliatory tariffs ultimately raise costs for domestic consumers and businesses — political and strategic considerations frequently dictate a different course.

After the initial announcement of US tariffs, Canada announced a 25% tariff on CA$155b worth of US goods, with an initial CA$30b in tariffs taking effect on February 4, 2025, and the remainder implemented gradually. These measures targeting key US exports, including agricultural products such as dairy, fresh vegetables, fruits and processed foods along with alcoholic beverages and a broad range of consumer goods, such as household appliances, clothing, footwear, furniture and sports equipment, were also suspended for a month. Mexico had signaled its intent to impose retaliatory tariffs, though details weren’t disclosed.

Meanwhile, China’s Ministry of Finance has adopted a measured and targeted response, announcing that it would levy a 15% tariff starting February 10 on certain types of coal and liquefied natural gas and a 10% tariff on crude oil, agricultural machinery, large-displacement cars and pickup trucks. These would represent about US$15b, or 10% of Chinese imports from the US.